Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Ingmar Bergman Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

Ingmar Bergman is a tortured auteur who wrestled with his spiritual and personal demons almost every single time he directed a film, produced for the stage, or wrote. The biggest filmmaker to ever make it out of Sweden, Bergman’s prolific career is full of challenging, thought-provoking cinema which has influenced nearly every director to work after his prime (including Martin Scorsese, Andrei Tarkovsky, Woody Allen, Jonathan Glazer, and many more). During a time when many directors were using film as a form of escapism on the big screen (with expansive worlds to explore, leaving our woes behind in Technicolor), Bergman was trapping us within our own minds in claustrophobic fashion, forcing us to confront our fears and dreads. While not the most appealing trait on paper, no one helps us unravel our fears, curiosities, and alienation quite like Ingmar Bergman. Whether we’re placed in a confessional booth in a cathedral, a psychiatric ward’s padded four walls, or a theatrical stage stripped of its frills and down to a minimalist state of limbo, Bergman has always fixated on the sensation of abandonment and desperation. His films exemplify purgatory, be it in the afterlife or here on a struggling planet amongst those in an uncaring civilization.

I’ve been waiting to rank this director’s motion pictures for far too long, so much so that I’m releasing this ranking of every Ingmar Bergman film without any real reason to (no major dates are attached to this article) outside of the fact that I would proudly call Ingmar Bergman my favourite director of all time, and have done so for the better part of almost twenty years. I was an undergrad student when I borrowed The Seventh Seal from York University’s Sound and Moving Image Library, placed the DVD in one of the computer lab towers, and sat transfixed, feeling as though the entire campus just dissipated around me as I watched humans succumb to the plague and society burn (quite literally in one scene). From then on, Bergman and his works became a bucket list challenge of sorts. I met one of his veteran actors and ex-partners, Liv Ullman, during an In Conversation With event’s Q&A at the TIFF LightBox back in 2018 (which I will gladly gush has been recorded and is online to see here). I’ve gotten the signature of another member of Bergman’s troupe, Harriet Andersson, and have it framed on my wall. One of my favourite film experiences ever was seeing Persona on 35mm (particularly the moment where the projector breaks itself on the big screen and with the projector’s light helping to sell the illusion, which remains an unparalleled moment for me as a cinephile). I have yet to reach Bergman Island (or the island of Farö, where Bergman frequently worked), but hope to do so one day. You better believe I purchased Criterion’s Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema box set as soon as it was announced.

With all of this squeeing, I will also be the first to admit — if not Bergman himself — that not every film Bergman ever made was perfect. In fact, you’ll find at least a few mediocre to outright bad works below (but we will be getting those out of the way first). They’re easy to forgive, considering that I would consider at least twenty of his films masterful-to-perfect in quality, which is a larger body of work than most directors’ entire filmographies. I will be focusing on just the feature-length films, of which there are a staggering forty-four to get through. I won’t be including any shorts, segments of anthologies shared with other directors, documentaries (tossing in his two doc features feels a little silly), or the recordings of Bergman’s stage productions. While I hold many of these projects in high regard, this list will become impossibly long to the point of exhaustion (for me as a writer, and for you as a reader) and I think it will become a lot more muddled. Focusing just on Bergman’s feature-length narrative works feels ambitious enough already, and it still possesses enough directness to work.

There is much to get through, as you can tell. Many works featuring legendary actors like the aforementioned Ullman and Andersson, plus Max von Sydow, Bibi Andersson, Erland Josephson, Ingrid Thulin, et cetera, et cetera. Numerous collaborations with other visionaries including master cinematographer Sven Nykvist, renowned editor Ulla Ryghe, and compositions by modernist musician Lars Johan Werle (amongst many others). Decades of compelling, multifaceted, harrowing cinema. Over one hundred years of Bergman’s existence and lasting inspiration. Many grapples between us and society, God, and our own minds. A plethora of dilemmas and yet they never feel the same each time (nor do they bring forth similar solutions). Even Bergman’s worst films are full of passion, quests for artistic and narrative experimentation, and fresh ideas. With the pummelling, distressing, depressing visions Bergman placed on the big screen came a catharsis for the rest of us: we felt seen within the cinematic vulnerability, and our inexplicable feelings and thoughts somehow became labelled and figured out. As a soul-searcher, questioner of the inner workings of the human mind, and challenger of the perceived and real national identities of Sweden, Bergman forever pushed himself. In his endless missions, he became one of the greatest directors of all time. Here are the narrative feature films of Ingmar Bergman ranked from worst to best.

Note: for the films that have multiple versions (theatrical and television), I always consider the fuller, longer, television versions to be the definitive ones in Bergman’s career, and those are what I will be ranking here.

44. This Can't Happen Here

All but disowned by Bergman himself, not included in the Criterion boxset, and hard to find (outside of its wide availability on YouTube, mind you), this film about refugees is a rare thing in the Swedish master’s filmography: forgettable. Not the worst film ever but easily Bergman’s least interesting film, This Can’t Happen Here is as watered down artistically, narratively, and creatively as he’s ever been. For Bergman obsessives only.

43. Crisis

Bergman’s feature-length debut, Crisis, is a noble but highly flawed work of passion. With enough artistic ideas to feel like it should matter, you’ll find that this first film possesses many of Bergman’s latter traits (complicated family dynamics, a disassociation from his motherland, psychological fragmentation) which may make this film feel like a trinket for Bergman superfans, but you’ll also quickly find that Crisis just doesn’t hold up to most of his other films. Still, there’s at least some slight value here.

42. A Ship Bound for India

I feel like A Ship Bound for India, which was up for the Grand Prix at the 1947 Cannes Film Festival, likely felt better upon its release as opposed to now (it feels a bit of its time and stale). Still, there’s a hungry filmmaker striving for greatness with his third feature film here, even though this ship seems to take its time (it’s only one hundred minutes, so lethargy is not a good thing to have with such a short run time, if ever). A bit more traditional and safe by Bergman’s standards.

41. It Rains on Our Love

Bergman’s second film, It Rains on Our Love, feels like the blueprint of so many other Bergman greats like Summer with Monika or From the Life of the Marionettes (all experiments on what a troubled relationship look like in Bergman’s mind). Furthermore, the concept of the “Man with the Umbrella” representing a higher being watching over these plagued lovers reinforces Bergman’s permanent tug-of-war fascination and frustration with religion, albeit presented a little clumsily here. A nice effort but nothing more.

40. The Serpent's Egg

One of the only English language films in Bergman’s arsenal, The Serpent’s Egg feels like one of Bergman’s greatest misfires (it is incredibly dull and uninteresting by his calibre). The saving graces are Bergman’s expertise as a director bringing out the artistic and psychological potential from within this unfortunate dud of a film. I’m being harsh with this one compared to some of the lower-ranked films because Bergman was still trying to figure out where he stood before (so their imperfections are understandable). With The Serpent’s Egg, he had already made many great films, so how he missed the mark so greatly here is puzzling (especially since the subject matter of one man’s struggle in a suffering Weimar Republic seems so fascinating).

39. Port of Call

Bergman’s answer to Italian neorealism, Port of Call, is a well-intentioned look at melodrama and hardship, even though the sugar-coated ending kind of nullifies much of the experience for me; I don’t expect Bergman films to solely be miserable, but I think he would find how to better handle optimism later on in his career. A decent film to watch for the curious, but definitely not a starting point for Bergman newcomers.

38. In the Presence of a Clown

Bergman’s penultimate film, In the Presence of a Clown, is a series of hits and misses, ranging from some of the more interesting ideas of his later career (especially regarding how one’s mental health can be perceived with so few resources and settings, via a psychiatric ward) to some bizarre decisions I cannot shake off. Some interesting notions about what art can be as a confessional device are present, so this concept alone makes this film feel worthwhile to some degree (but maybe don’t start your Bergman journey with this one).

37. Secrets of Women

An okay effort by Bergman, Secrets of Women feels like another uncharacteristically simple film from a director known for pushing boundaries. An anthology film in hiding, we follow the recollections of confessions via a handful of women as they gossip. It’s a neat idea on paper, but it winds up being a pleasant-yet-forgettable experience that won’t stick with you even five minutes after you’re done watching it. Still, regarding early Bergman, while there are far better films, this is one of the more cohesive efforts when discussing the weaker projects: it’s less expressive or artistic, but it’s at least solid while being undaring.

36. The Devil's Eye

I know Bergman has a prickly relationship with his spiritual side, but his representation of Satan in The Devil’s Eye is a rather buffoonish one (which may be good news, depending on who you ask). One of the sillier and more whimsical films in Bergman’s career, The Devil’s Eye is not meant to be taken too seriously; it’s also rather impossible to even try to, if I’m being honest. Bergman doesn’t always handle comedy extremely well. On that note…

35. All These Women

Most would call this satire of Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 Bergman’s worst film, and it isn’t hard to see why. For me, I think All These Women is overly hated not because I think it’s good, but because it’s clearly meant to not be good. If you allow the film’s stupid antics to stun you (in ways) amidst the cinematographical choices by Sven Nykvist (which, quite frankly, are far too great for a film this silly), then Bergman’s first colour film won’t seem too bad. Don’t expect anything, and All These Women won’t offend you as much as it has others. Just expect nothing at the same time.

34. Thirst

Bergman’s last film of the forties, Thirst is yet another noble early effort that has some strong ideas regarding the problems in one’s marriage while also relying a bit too much on that promising ending (perhaps as to not dive into despair too early in Bergman’s career). A bit more balanced than its peers, Thirst is a bit more spicy and colourful than the films that preceded it.

33. Dreams

An anthological film (of sorts), Dreams has a handful of dream-like stories (given the title) that all feel strong enough on their own, yet amount to very little when combined together outside of being a nice idea. Still, what helps Dreams a bit more than Secrets of Women is the subconscious, spiritual understanding of what is going on in each story, as Bergman was exploring himself as a human and an artist a bit more with each and every film.

32. The Touch

Bergman’s first English language film, The Touch, was hated so much that even Bergman distanced himself away from it. I don’t think it’s quite that bad, while not being up to the bar that he set for himself by this point. An honest attempt at the romantic, historical drama, The Touch indeed falls flat as many will tell you, but these naysayers are also missing the glimpses of heart and perseverance found within. I won’t pretend that it’s a masterpiece, but The Touch is needlessly flogged when he for sure has worse films.

31. Music in Darkness

Perhaps the earliest point in Bergman’s career where the director finally had a spark that was noticeable enough, Music in Darkness incorporates the common ground between passion and musical artistry in this fascinating drama about a blind pianist’s love with a servant girl. While Bergman would go on to do greater things, I think Music in Darkness is slept on and would easily be his best film of the forties, if it wasn’t for…

30. Prison

It feels like Bergman was already turning the camera on himself with a film like Prison, as we follow a director on an impossible quest (who picks up on the disdains and devastations of others). While a bit muddled with too many ideas, Prison is mostly successful by early Bergman’s standards, as we see the filmmaker already questioning the means of film as a narrative and artistic device (and how much it can perceive the human experience). Of course, Bergman would get far more experimental with his meta-commentary, but Prison is a neat early experiment of the same hypothesis: what can a director say about film using the very medium?

29. The Blessed Ones

One of the most stripped-down films in Bergman’s career, The Blessed Ones is a late-stage drama and the last time the director would adapt a screenplay by Ulla Isaksson. A television production which feels like a stage play, The Blessed Ones is Bergman’s umpteenth examination of an ailing mind. By this point, this was old news and derivative, but The Blessed Ones is still a moving film where an older Bergman was clearly still plagued by these fears and needing to cleanse himself of these demons.

28. Brink of Life

One of the better “anthological” films in Bergman’s career, Brink of Life has three mothers-to-be questioning whether or not they wish to keep their babies (or if they should allow them to be adopted by other budding parents), and each woman’s concerns and thoughts pose a different perspective on the dilemma. A more thoughtful take on why a film should be this divided into subplots while clearly a finger pointed at the Swedish government at the time.

27. A Lesson in Love

A straightforward look at the romantic drama, A Lesson in Love has Bergman trying his hand at something a bit more digestible and simplistic while succeeding decently enough. It almost feels like Bergman is acting like his own William Wyler here, trying to extract a great amount of passion and heartbreak from this onscreen love with enough of a self awareness in scope and drama to make most points matter.

26. Saraband

Bergman’s final film is a return to the characters of Marianne and Johan from 1973’s Scenes from a Marriage, almost like his answer to Richard Linklater’s Before series. Decades after their divorce, we catch up with these two drifting souls and what their lives are like now (and we question how happy either of them truly are at the same time). A sublime television film by Bergman that seems to put a full stop not just on this ongoing story between Marianne and Johan but on his career as well; I can’t think of a more fitting swansong.

25. To Joy

Bergman’s first film of the fifties is far better than the release of This Can’t Happen Here in the same year. To Joy questions the correspondence and cooperation of two violinists in the same orchestra, in life, and in their own respective marriages. It’s a powerful statement on the importance of cohesion in society and in art made by a director who had a half-dozen films under his belt by this point and was starting to recognize not just the hardships in making films but also the capabilities that he possessed.

24. From the Life of the Marionettes

From this point on, consider every entry great to excellent (yes, Bergman has this many hits). An underrated psychological drama and an eerie, uncanny film that must be seen by the biggest Bergman fans, From the Life of the Marionettes is an aesthetically and narratively unsettling affair which takes the concept of a failing marriage and dials it up to ten (while the rest of the production is boiled down to a minimalist state). Of the many Bergman films that get their share of adoration, Marionettes is criminally slept on by all but Wes Anderson who has praised it as Bergman’s best. I wouldn’t go that far, but it is a terrific film that deserves more; it may become your favourite, too.

23. The Magic Flute

While the thought of an opera film isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, Bergman’s attempt at the genre is one of the finest you may ever find. His adaptation of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute is one that is both faithful and progressive, as Bergman turns the point-of-view on the audience of the late composer’s masterpiece enough times to make us feel as though we’re a part of this spectacle (one which is always knowingly a production, and yet we get swept away nonetheless).

22. After the Rehearsal

Released late in Bergman’s career, 1984’s After the Rehearsal is his most stripped-down film, but its brilliant concept carries it from start to finish. After so many years dealing with stage productions, it makes perfect sense that Bergman would make a film about the after-hours period during rehearsals, and the sense of what devotion can be (to the stage and to one’s craft, as well as to life and relationships). Tethered entirely to conversations, mainly by Erland Josephson and both Ingrid Thulin and then-newcomer Lena Olin, After the Rehearsal is a masterclass in dialogue-driven tension.

21. The Rite

Easily Bergman’s most overlooked film, The Rite deserves to be in the same conversation as his other experimental works; while not being quite as strong, The Rite is easily as daring and shocking (especially considering this is a television release, and Bergman’s first at that). A relentless look at cultish acts and psychological breakdowns and horror, The Rite builds up to a highly unsettling climax that will be impossible to ever shake off. It is a terrific film that was shrugged off as bleak and confusing upon its release, and I think it’s time to give The Rite the proper reevaluation it deserves.

20. Shame

A harrowing look at love, war, death, and abandonment, Bergman’s Shame has grown to become a beloved film nowadays (and rightfully so). The characters present here — a happy couple to be tested by the events of a civil war — are given so much depth as people and as individual thinkers that Shame’s eventual collapses make their downfalls feel so much weightier. The final images here are ones full of desperation and hopelessness; they’re guaranteed to leave you cold. A devastating film, but what else is new when Bergman was working at peak level?

19. Face to Face

While Bergman has always worked with great actors and has been able to bring out the best performances out of them (for the most part), I’ll go out on a limb here and state what’s already been brought up many times before: Liv Ullmann’s performance in Face to Face may be one of the greatest of all time. As we watch a psychiatrist swap places and be on the receiving end of care for her mental decline, we stare despair straight into its eyes. An anxious, tumultuous affair, Face to Face is obviously relentless but an essential look at psychological turmoil and representation in film (around the time that the stigmas surrounding mental health were beginning to pivot).

18. The Passion of Anna

One of Bergman’s boldest choices — to polarizing effect — was to split up his 1969 melodrama, The Passion of Anna, with interviews with the stars of this very film; this was to pick their brains on what they perceived to be happening to their characters in The Passion of Anna. This is a move that would make Abbas Kiarostami proud well before the Iranian auteur was making similar decisions. Otherwise, The Passion of Anna is a hectic, constant wave of tension made by a director who was beyond done with playing by the rules, and it holds up tremendously.

17. The Magician

The last Bergman film of the fifties, The Magician, is an askew look at religion and spirituality through the guise of the titular showman and his touring illusions (and how they are picked apart by non-believers). What helps make The Magician work so well to the point of being a cult favourite within Bergman’s works is how deeply into your soul and under your skin the film drills itself, making you feel both uneasy and uncertain at almost all times. He would perfect the concept of what a Bergman horror could be later, but The Magician is a terrific early attempt to close out his first major decade.

16. Sawdust and Tinsel

As we’re creeping towards the top of this list, this will likely be the last time I feel comfortable calling a Bergman film underrated, but I do believe that Sawdust and Tinsel deserves this designation. A strange look at what a love triangle and existential crises can look like via the symbolism of a travelling circus, Sawdust and Tinsel is a reminder that our tragedies become the fodder of cynics and society and that life is only what we make it. The film also boasts one of the stronger uses of a clown in film history via Frost, whose performance by Anders Ek is sure to break your heart despite the perception of patheticness by those around him who only mock and never help him in his darkest hour (it’s truly Pagliaccian in nature).

15. The Virgin Spring

While an early influence on the revenge genre (and Bergman’s first Academy Award-winning film for Best International Feature Film), The Virgin Spring is wrongfully perceived just as a tale of comeuppance when it is so much more complicated than that. As a broken father seeks vengeance, we are tasked with scrutinizing his actions and questioning how they hold up in the eyes of God (a debacle of morality Bergman often posed). Of course, we will side with reason here, but The Virgin Spring is pure tragedy that pulls us through the mud before making us grapple with how we respond to monstrosities and grief.

14. Summer Interlude

Given the number of early Bergman films we sifted through before reaching his strongest works, it’s as clear as day that his turning point as a director is the blissful yet monumental Summer Interlude of 1951 (curiously released right after his worst film, This Can’t Happen Year, as if he savoured all of his ideas and inspiration for this film instead). Using the art of ballet to portray the crescendos, rises and falls of a ballerina’s life, Summer Interlude is pure cinematic poetry. It also remains one of his more accessible films to the masses; despite how deep the film gets, Summer Interlude is not challenging or provocative by Bergman’s standards, but rather human and beautifully universal.

13. Winter Light

An earlier film where Bergman aimed to bring the vulnerability and closeness of stage productions to the big screen, the existential, frigid drama, Winter Light, brings us right into the comfort zones of those who are hurting. Whereas Bergman often portrayed his difficult relationship with religion via symbolic means or through narrative tangents, Winter Light sees this conflict as directly as Bergman’s ever been, as we are placed in the cold and dark and asked to face our own spiritual strength amidst those who are on the verge of cracking. Winter Light has become a fan favourite for many Bergman super-fans and it is easy to see why.

12. Hour of the Wolf

One of the cases where a Bergman film wasn’t necessarily cared about upon its release yet has gone on to become a cult favourite, Hour of the Wolf is the finest instance where the auteur went full-on horror. What drives these nightmarish images and sensations? Claustrophobia and sleeplessness, of course (the kinds of fears Bergman battled daily). As we are brought to a point of psychological delirium, we are also introduced to the depths of Bergman’s anxieties; his vulnerability being so open allows us to fully understand and feel the nausea he intended for us to wrestle with.

11. The Silence

While some other Bergman films may have dealt with surreality and experimentalism more abrasively, I adore how sporadic and seamlessly The Silence deals with its abnormalities, as if we are coasting in and out of consciousness. Perhaps a precursor to Persona, The Silence has us seeing two sides of one woman via a pair of sisters and their uneasiness with each other and a nation in crisis. As we question what we see at any given point, The Silence reveals itself as an unusual cinematic experience that will leave you stunned upon your first watch and unsure of what will transpire next.

10. Autumn Sonata

Autumn Sonata is pivotal for Bergman. It’s the only time he worked with the similarly named Swedish superstar Ingrid Bergman (no relation), in her final performance no less. It’s the last time any of his films were released strictly for movie theatres, as he grew an affinity for making television works after Scenes From a Marriage. What we get is an acting masterclass between Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann via a stripped-down study between a strict, perfectionist mother and her sheltered, fragile, grieving daughter. Using the art of music (technicality versus meditativeness) as a means of bringing both women together while also causing them to drift further apart than ever before, Autumn Sonata is a sensational drama that needs very little in order to permanently shape you.

9. Smiles of a Summer Night

While Bergman wasn’t a constant practitioner of comedies, Smiles of a Summer Night was the rare instance where he nailed the genre and its conventions (oddly enough, it was at an extremely low point of his career that he joked about ending his own life should this film not succeed). A wonky look at what a sex comedy can look like (with some major stakes to boot, including a game of Russian roulette, no less), Smiles of a Summer Night almost feels like Bergman’s answer to Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game: an exhibition of privileged humans acting like absolute idiots in the name of pride, love, and obsession. Bergman’s best films don’t get lighter or funnier than this, folks. It’s an against-type miracle.

8. Summer with monika

We all have dreams of escaping our difficult lives, and Summer with Monika tackles that fantasy head-on with some harsh acceptances of what the realistic outcomes of such excursions from civilization may look like. Featuring a breakout performance from Harriet Andersson in what can only be considered a daring role for its time, Summer with Monika pits young adults against both society and the foolishness of their own desires. Considered sexually taboo upon its release (albeit incredibly tame by today’s standards), Summer with Monika is now considered a watershed moment regarding sexual liberation in Sweden in the fifties. It’s also a reminder of something Bergman often thought about in his films: you don’t always get what you want.

7. Scenes from a marriage

Bergman’s longest affair is the six-hour television opus known as Scenes from a Marriage: a thorough analysis of a seemingly happy marriage that slowly unravels into the drifting apart of two apparently lonesome souls. Bergman takes his time with these characters and their developing qualms, mainly stemming from their observations of the unhappiness of others within themselves. Despite the hours of sadness, Scenes from a Marriage shockingly winds up concluding with an unusual sense of optimism and hope from Bergman: that there can be joy and freedom within hardship. Despite many attempts at recreating this film (down to a 2021 HBO adaptation), it seems nearly impossible to capture the rawness of Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage.

6. Through a Glass Darkly

It might seem high on this list, but I have been spellbound and haunted by Through a Glass Darkly since I first watched it many years ago. This capricious psychological drama plants us in the predicament of watching a loved one lose her mind, and in a situation where there can be no help around (as expected, we’re on location on the island of Farö, where Bergman would revisit time and time again after this first film). Through a Glass Darkly is willing to go as deep and dark as possible, to outright shocking lengths. Its conclusion may seem a tad chipper, but I find it intentionally paradoxical, as if we are responding vaguely via trauma, or if Bergman was disregarding devastation in the way many blindly religious people may. Either way, Through a Glass Darkly is as uncanny as Bergman’s films ever got, and this indescribable panic and dread it makes me feel will never leave me.

5. Wild Strawberries

What happens when we get older? Bergman’s depictions of one’s battle with death or race against time were usually involving far younger characters as if to say we waste our lives worrying about our mortality (rather than living properly and giving our lives meaning). Then there’s Wild Strawberries, where Bergman has a geriatric professor revisiting his life through the youthfulness of others, destinations on a road trip, and even nightmares. As he heads towards Stockholm to receive a degree for his hard work, he wonders where it all went before realizing where the purpose in his life truly lies. Wild Strawberries is excruciatingly beautiful with its prose on what matters most in life, made by one of cinema’s most cynical minds. It’s the kind of film that can rewire your brain into reconsidering how you live from this point forth.

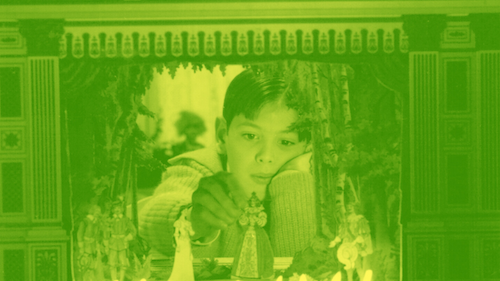

4. Fanny and Alexander

While initially intended to be Bergman’s final film (it wound up being his last theatrically released work whilst bridging his latter career television efforts), Fanny and Alexander still encapsulates his career as well as any summary could. This five-hour period epic starts with a lengthy Christmas celebration before turning to a tragedy that shakes up a family (and with horrifying ripples that affect them for years). The young Alexander represents Bergman staring at himself as a child with many autobiographical elements tossed into this harrowing, occasionally supernatural affair. As a punishing father-figure of the cloth (again, Bergman’s life is present here) stains an otherwise happy and ordinary family, Alexander tries to save both his loved ones and himself. These many hours build up towards a tremendously bittersweet ending with one of the greatest twists in cinematic history: a blessing for all that becomes a damning curse for one.

3. The Seventh Seal

Most frequently considered Bergman’s magnum opus (maybe twenty-plus years ago, before the internet got us more acquainted with other Bergman films), The Seventh Seal is nearly impossible to not feel through your bones. As we watch an allegorical depiction of death taking out people via the Black Plague — only for a foolish knight to try and prolong the inevitable via a now-iconic game of chess — we see the many different takes on distress and desperation that people experience while acknowledging that their time is wrapping up. We also witness the death of others via war and hysteria, while knight Antonius Block — and Bergman vicariously through him — ponders about the existence of God and wonders what comes next. As The Seventh Seal concludes and we get the famous Dance of Death, we realize none of it matters. We’ll never truly know what will happen once we pass. We cannot live in fear of what’s to come. Far less optimistic than Wild Strawberries, mind you, The Seventh Seal encourages us to be brave in the face of fatality, because our own strength may be all that we have.

2. Cries and Whispers

The aesthetic take on existential dread in Cries and Whispers is an unforgettable experience. The use of red, white, and black to represent blood, lovelessness, loss, death, sickness, guilt, and grudges will be burned into your mind. Watching a family of estranged sisters during the dying hours of one sibling is harrowing enough, but hearing their inner thoughts (in what may cleverly be Bergman’s deceptive take on anthological short stories) is a whole different level of gut-wrenching. Cries and Whispers feels impossibly invasive as if we are listening in to the prayers of the suffering, the breaths of gossipers and liars, and the agony of the broken. This world feels like a limbo — nay, a hell — of sisters who don’t even remember how to be human beings towards one another, all while the sickest of them all hopes — in vain — for times to be better again: a reflection of how we take life for granted when we still have many days and years ahead of us. Cries and Whispers is a painful masterpiece that is as effective and earth-shattering as cinema gets.

1. Persona

I will never forget the first time I saw Persona. Having seen a few of Ingmar Bergman’s other classics, I thought I was maybe prepared for this brisk, eighty-minute film that was mainly tethered to two performances (by Bergman mainstays Bibi Andersson, as nurse Alma, and her patient actress Elisabet, played by Liv Ullmann) in one main setting (a cottage on the island of Farö). Elisabet can no longer speak, and Alma is to help her regain this ability. As soon as I started watching Persona, I was ambushed by the shot of a projector warming up, a countdown featuring a “6” I never accounted for, and a parade of shocking, mysterious images, ranging from a slaughtered sheep and a crucifix to a boy waking up to ghostly faces after sleeping in a morgue. We cannot trust Persona whatsoever from this point on, even when the film cuts to its main story of a nurse and an actor. As the film progresses, Alma and Elisabet become indistinguishable from one another, blurring the line of who is who (or if they are one person [and, if so, who are they] or anyone at all); Persona as a film proceeds to break itself time and time again.

This is a post-modern masterpiece and an unflinchingly-made avant-garde opus made by a director who had all the reason in the world to release lazy, conventional films after already having so many beloved works by this point. Made right after his most goofy film (All These Women), Persona is not only Bergman’s most serious work, it is easily his most challenging, and one of the toughest films in all of cinema. Its rewards are singular. Never has there been a film like Persona, despite the many works influenced by it (many are favourites of mine, including Mulholland Drive, The Double Life of Veronique, and 3 Women) because of how it destroys itself as a film, as a story, and as a single mindset. To see a film get deconstructed and pieced back together in a way that provokes us to reassess why we love cinema is a treat I’ll never forget.

Even though Persona is all about being antithetical, it gets so many of cinema’s different elements so perfectly. It has two of the greatest performances. Sven Nykvist’s cinematography is unparalleled yet highly homaged. Ulla Ryghe’s editing helped change how films can be pieced together while still playing the part when necessary. Persona is as inviting as it is alienating, as it encourages us to peer closer before decimating itself when we have our arms open to finally embrace it. After countless rewatches, I still don’t have a perfect answer as to what is happening in Persona, nor do I want this closure. I can confidently proclaim to have seen over ten thousand films in my lifetime, and yet none are Persona. It feels next to impossible for a film to render me speechless or incapable of figuring it out through and through, and yet Persona — a film I have been all too familiar with for decades — continues to leave me questioning, leaving me out in the cold to decipher what this artist has made for us, only for him to desert us in our time of need (again, there’s that tricky relationship with God Bergman always had).

To watch Persona is to understand film as a principal medium, its conventions, its rules being broken, and its limitless capabilities that aren’t allowed to exist nearly enough throughout the course of cinematic history. Not only do I consider Persona to be Ingmar Bergman’s magnum opus (which is high praise, considering how many breathtaking and important works he has made, in my opinion), but I consider it — with quite some assuredness — to be the greatest film I have ever seen. The older I get and the less sure about life and the unknown that I am, the more certain I am that Persona is cinematic perfection. Naturally, that can only mean that it was always going to top this list, and yet I still feel so happy to place it here. Persona, to be, is the best of the best, by the best to ever make motion pictures.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.