Wings

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Wings won the “Outstanding Picture” award (later changed to “Best Picture”) at the very first Academy Awards in 1929.

The very first Academy Awards actually had two Best Picture winners: “Best Unique and Artistic Picture”, which went to Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, and “Outstanding Picture”. The latter award went to the World War I romantic drama Wings, and — for the sake of deciphering what these two categories mean — it’s the perfect winner. Sunrise is a symbolic interpretation of repairing a broken relationship. Wings, on the other hand, was a fairly basic love-triangle film, told with some absolutely bonkers technicality. If Sunrise was the expressionist painting, Wings was the well-assembled matchstick sculpture that focused on precision and initial shock.

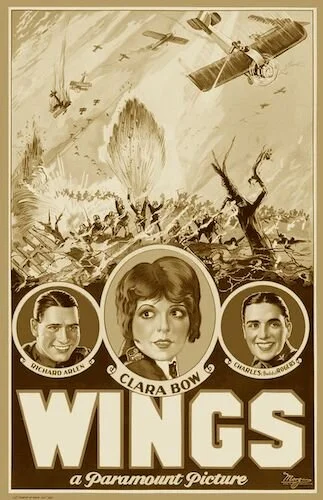

Leading up to the recession (and with America still feeling the effects of their first World War), Wings was aware of the struggles between classes. Thus, it presents two town pretty boys (played by Richard Arlen and Buddy Rogers) trying to grab the attention of their loved ones and the local woman they are booth swooning after. A fourth player is tossed into the mix in the form of Mary (played by Clara Bow), who loves Roger’s character Jack. So, we have two men of different backgrounds fighting for one girl and neglecting another, using the war to prove their worth to their country and themselves. It’s a standard plot, but still nuanced enough to keep you interested.

The three leads of the film together.

Wings boasts characters that try to make points through self sacrifice. This includes Mary, who joins the war’s medical department (and operates their ambulance). All three people see the horrors of war first hand. In Wings, presentation takes a precedent over weight. You still feel as though the war is a disaster, but it’s also so hard to only remember this during the combat scenes. The film is naturally titled after the use of aircraft battle sequences, because these are some of the film’s strongest attributes. In all honesty, I don’t care how old this film is, those flight sequences are still breathtaking. You can argue they haven’t aged well, but I would think you were being overly cynical in this case. For what they are worth, these moments will have you arrested in your seats.

That’s where the film truly excels. Its narrative is not lacking by any means, but you are compelled by how these plot points are executed. Cinema did not start in 1927, and the Academy started decades after films were even being treated as proper story telling devices (let alone the actual invention of filmmaking), but it strangely feels like Wings was built for the Academy (despite it being the first year of the ceremony, there being zero audience appeal, and the lack of standards on how to win since, again, this was the first year). Wings is a display of technical prowess that never lets up.

A snippet of what some of the flight sequences look like: well choreographed effects that still hold up rather well today (all things considered).

I talk a lot about how the film is presented, but I’m not even talking simply about the war scenes at this point. Even the sit down moments are presented in a rather interesting way. This includes one of my favourite deep-focus shots of early cinema: a “zoom” that coasts past a number of dinner guests, until the picture fixes on the focal points at the end of the room. For 1927? That’s pretty damn impressive. There are also little treats, like the bubble effects to imitate a drunken stupor. Again, Wings feels as though it was crafted to win awards, when that clearly isn’t the case, since an understanding of how to win over an academy simply didn’t exist back then. I’m not saying Wings is the only well crafted film of this time (not even close: the silent era is remarkable), but this particular film just screamed “Oscars” before they even existed. Perhaps this first Best Picture win set the standard?

Well, Wings was progressive in other ways as well. Believe it or not, it is the first Best Picture winner to include nudity of any sort: not only that, but it was one of the very first feature films to include nudity period. Wings also was the very first instance of any feature film featuring two men kissing, and two women holding hands (with the implication of a relationship). I can’t be certain of director William A. Wellman’s intentions for these moments, but the bar was still set. One last factoid: excluding Sunrise (which both counts and doesn’t count as a Best Picture winner), Wings is the first and last truly silent film to win Best Picture (The Artist is the closest second, but that’s also a debatable “silent” film). That’s pretty bizarre to think about. Wings and the Academy arrived at the tail end of the silent era. Some prints (and the remastered version of the film) have recorded sound effects and music, but otherwise, this is it. Everything else from here on out is a sound feature.

The iconic deep focus shot.

For a relatively standard story, Wings is presented with all of the intentions of progressing how stories are told. Again, it’s so appropriate that Sunrise won the more artistic based Best Picture award (considering its aesthetic nature), and Wings won what feels more like the “best produced” film award. Sunrise knew how to fine tune the elements of filmmaking, but Wings hunted for ways to challenge how these elements even worked. As the very first Best Picture winner, it’s easy to see why this film wowed over critics over ninety years later. It seems silly, that I am so fixated on how solid this first winner is. You’ll quickly learn that not every early Best Picture winner is good. You’ll learn that a lot sooner than you think. Luckily, Wings is not one of those films.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.