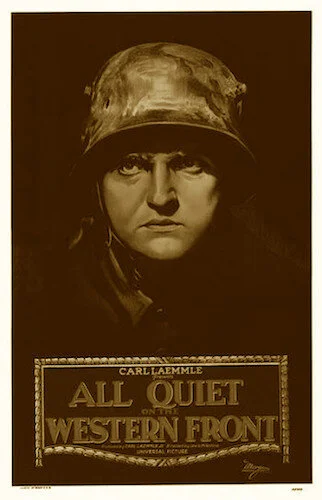

All Quiet on the Western Front

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. All Quiet on the Western Front is the third Best Picture winner at the 1929/1930 Academy Awards.

Is it any coincidence that All Quiet on the Western Front was already the second Best Picture winner to discuss war (after Wings)? I don’t think so. Clearly, the effects of the first World War was still echoing throughout the world a decade later. It almost felt necessary for this film to follow up Wings. The former film turned the first World War into a technical spectacle, with some fairly strong statements on how the war rips lives and relationships apart. Well, All Quiet on the Western Front went all in. No prioritized love stories. No apologizing. It’s straight up anti-war horror. It feels like an over-two hour lesson to know what one gets themselves into when they sign up for the war. Down to the last second, All Quiet is a foot on the throat that never steps off. It’s pre-code Hollywood in all of its unfiltered glory.

Like many films of its kind, All Quiet is a very basic story: a group of schoolboys are encouraged by their authoritative figures to join the army. They see this as a club, and a way to honour their identities by serving their country. Things get ugly very quickly, when bootcamp is already the squashing of hopes and dreams. But, that’s as bad as it gets, right? Absolutely not. The majority of All Quiet takes place on the battle field, and I do mean the majority. Like the riskiest army films that know what they’re doing (I’m thinking The Thin Red Line as one example), All Quiet tells very little, and shows everything. Not much narrative progression happens for at least two thirds of the film, but you get the bigger picture through all of its representations. The weird take way is that this doesn’t even feel excessive. Somehow, All Quiet fulfils its task of feeling like the never ending hell of being stuck in a war you were disillusioned about joining.

The soldiers trapped in their camp like sitting ducks.

One key element I adore is how the film doesn’t really have a star until a turning point occurs. You follow a whole group of men until the return back to civilization, where you are placed in the shoes soldier Paul Bäumer having to represent all of his dead associates. We’ve seen many films tackle the change one’s world goes through once they’ve faced war, but All Quiet nails this feeling so well (especially for a film from 1930). Since you don’t follow Paul by himself the entire film, you don’t quite feel inclined to know his every move. By being left with him after his first instances of war, you begin to understand what a responsibility this is: you have to be the face of the fallen, despite the fact that you want to forget it ever happened altogether.

Part of the success of this message comes from the well choreographed war sequences, that never seem to end (but that’s precisely the point). There is carnage after carnage. Some of these effects are a little dated, but still strong for their time. The rest of the effects are still mind blowing, even today. It’s not about wondering how they did these effects, but just admiring how they were pulled off. I’m talking about bombs being dropped, the amounts of soldiers turned into lifeless corpses, everything. Even today, parts of these scenes feel convincing, and like you are witnessing a bloodbath. I can’t even imagine how direct these moments were to audiences back in 1930.

Part of the film’s staying power is how well crafted the combat scenes are.

All Quiet is a part of a time in film history when things got a little confusing. Do we release a silent film, given that sound is not perfected yet, many theatres were still adapting to project sound films, and audiences were still used to how silent films operated? Sometimes, films were shot silently, and had sound included after the fact. All Quiet was shot as both a silent and a talkie film, in a way. Two cameras were used for each and every scene, side by side (resulting in a slightly-skewed second copy), with one batch of rolls intended for sound releases, and the other for “international” release for foreign distribution. This doesn’t make the biggest difference with the most common sound copy that circulates today, but you can still notice how some scenes have the theatrics of the silent era still crammed inside of them. The war scenes almost play out like silent films, where the screams and gun shot sounds play like the cacophony-spewing orchestra reacting to what they’re seeing.

So, we get it. The war scenes are soul sucking. Part of how they work is all the build up to these moments. This includes the joy found in the earliest scenes, the slightest glimpses of foreshadowing that predicted their fates, and the starkly different training scenes. Those bootcamp moments were a melody in comparison to where the film goes. All Quiet wanted to make a point, and it understood how the flow of a film could dictate that point. Just making everything gory wouldn’t work. We had to get sucked in, and invested with a lot of impressionable faces.

The horrors of war in the form of a super imposed image of an endless graveyard.

Director Lewis Milestone is the bridge between many of these elements. He knew how to transition into a sound film, whilst utilizing the best qualities of the silent era (given his experience during said era). He had enough of a cinematic understanding to know how to fire on all cylinders, yet not give away all of his tricks early on. Sure, most of the film is lodged in the war, but a lot of it is trying to simply get out of this situation. This includes being stuck in underground bunkers, trapped on the war field, and seeing the barbed wire preventing your escape.

By the end, we are alongside Paul, who is still permanently broken by the war, the lies of his community, and the monstrosities of humanity. The ending is as blunt as it can be. Paul is stuck in war, because it could never leave him mentally, and he is valued only for his services. He extends his hand out to a butterfly: the last signs of life he’s ever going to experience. Every human around him — deceptive, cold, or the enemy — is dead (often literally). Humanity destroyed nature, and it’s destroying itself. This butterfly is the first hint of life he has seen in years. That’s it. With life comes death. All Quiet is anything but quiet.

The now-iconic shot of Paul reaching out to interact with the butterfly, while both are trapped in the trenches.

All Quiet on the Western Front remains a pivotal piece of anti-war cinema, because of how high it set the bar. Unlike The Broadway Melody the year before, which opened the door for musicals and allowed better films to walk past it later on, All Quiet was relentlessly staking its claim from the first second. However, I doubt that Milestone and company were concerned with being the best film of its kind, but rather to convey a serious message in the best way possible. Sadly, the film remains relevant to this day, but its brilliance in all areas allows it to remain a strong voice in the war genre.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.