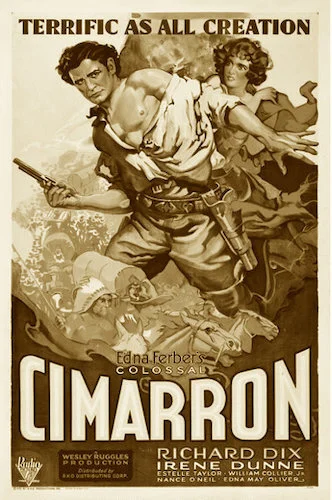

Cimarron

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Cimarron is the fourth Best Picture winner, and won at the 1930/1931 Academy Awards ceremony.

Whenever anyone wants to complain about Crash, Driving Miss Daisy, or, most recently, Green Book when it comes to what films win Best Picture, I feel like people are missing the bigger picture. Not that these other films are amazing by any means, since I would agree with their substandard quality. Rather, I feel as though these proclaimers are not familiar with some of the even worse films that won. Case in point: I can guarantee that they have not seen Cimarron: without question the worst film to ever win Best Picture. Even trying to put myself in the shoes of the early ‘30s public or Academy does not help. I have zero idea as to how this film won, unless the nominees were the worst in history.

Looking at the other nominees, we get a bit of a clearer idea as to how Cimarron won. Every single film has been rated rather lukewarmly by modern viewers. These include the comedy Skippy, the dramedy The Front Page, the now-insanely-insensitive Trader Horn, and East Lynne (which I have not seen, given that very few copies of the film exist). However, despite all of this, Cimarron still ranks the lowest ratings wise. Maybe this is because more people have seen it. The Academy couldn’t have given it to The Front Page (and given Lewis Milestone a two-in-a-row deal) or Skippy (which director Norman Taurog won an Oscar for)? Really?

The opening scene of the Oklahoma land rush is the only reason this film is worth watching.

My guess is that voters were hypnotized by the opening scene of the Oklahoma land rush of 1889, which, admittedly, is a fantastically shot and orchestrated sequence. I remember being extremely excited myself. I love a good western film, and knowing this was the first of a class of very few western films to win Best Picture had me champing at the bit. The amount of action going on is almost like you are in the middle of a circus, where every single direction you stare is worthwhile. And, just like that, the entire film comes crumbling down very, very quickly. We could have joined the stories of any of these settlers. We had to settle with the Cravat dunces. These include father figure and his holiness Yancey, his uncredited real-hero wife, and their barely noticeable son Cim (and later on his sister Donna).

We sit down with the privileged family, as their African-American slave (let’s be real here) fans them whilst hanging from the ceiling, and we already know this film is not going to age well. So, most of the film is how Yancey tries to adapt and take on a leadership role in the town of Osage. What we don’t know until later, is that this Yancey character is such a coward that abandons the family, town, and the film whenever he damn well feels like it. Much of the last third of the feature rests on Sabra’s shoulders, until Yancey sees fit to come back, save the day, then leave again. The film ends off with some dramatic nonsense to make us feel sorry for Yancey, and then he is crowned a hero. The hero of what? Leaving your family to die?

The look Yancey gives here is all you need to know about the film. The donkey male character is championed, and his relentless bride is not.

So Cimarron is blatantly racist, unknowingly sexist, and just a terribly made film that the “age” debate just cannot save. Excusing the backwards politics, Cimarron just makes for a lousy story. The hero comes and goes, and never really changes as a character. Any threat is quickly dealt with, or left for the wife to battle (and not get her dues for). Nothing comes close to matching that Oklahoma rush opening. There’s one moment of gunplay where Yancey strikes to save his own skin, and it’s honestly a breath of fresh air. Otherwise, this is a boring, insulting film that has a few minutes of saving graces; the rest of its duration is maddening. This truly is the worst Best Picture.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.