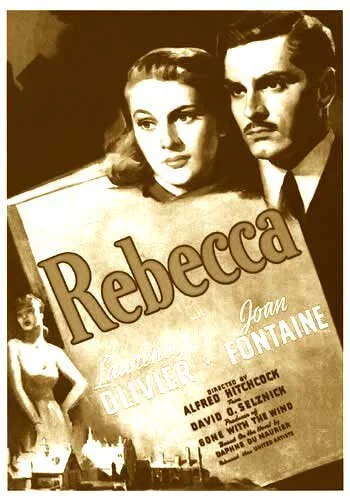

Rebecca

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Rebecca is the thirteenth Best Picture winner at the 1940 Academy Awards.

I have no idea what was going through the minds of Academy voters during the process of picking out the best film of 1940. David O. Selznick lit the world on fire (even literally) with his box office breaking Gone With the Wind. He was clearly the hottest producer in town (albeit a highly problematic person). Nonetheless, he was bound to strike gold again. Little did anyone know that he was going to be a part of a Best Picture winner literally one year after. If Gone With the WInd is a film based on heat, Rebecca is the cold antithesis: a mind bogglingly frigid film that remains one of the most intentionally lifeless films to win Best Picture. Usually, Oscar bait films are pedestrian, receptive, and inviting. Not this film. Rebecca is gothic cinema done perfectly. And it’s not entirely David O. Selznick’s doing.

That’s right. This is Alfred Hitchcock’s show, despite the overwhelming anomaly that this film came out when producers still had more of an impact on a film than directors, and this is very out of left field for even a Hitchcock film (so O. Selznick still had enough of a say in this film). What works the most is how unrelenting Hitchcock was to listen to O. Selznick. At the time, Hitchcock was beyond transitioning from silent films to sound (he clearly made the leap effortlessly), and he was establishing himself as an early auteur. As a result, much of Rebecca’s magic was Hitchcock refusing to give in: dark climaxes, grim sequences, and brushes with death galore. You can say that the Hollywood ending was a sign of weakness, but this was the 1940s. Chances are Rebecca wouldn’t have even sold if it wasn’t for some sort of easing up.

Rebecca’s fascination with ghostly imagery is an enduring quality that still takes breaths away today.

For most of the film, we are presented with a life of living mannequins: a marriage that feels lifeless, and plagued by morbidity. This is a theme that is blatant before you even start the film. It’s titled Rebecca. The lead character (played by Joan Fontaine) doesn’t even have a name. She is living in the shadow of a deceased loved one from the get-go. She falls in love and marries Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier): a man of luxury, class, and great fortune. He lives in Manderlay: a mansion that feels like its own character. As soon as the leads enter it as a new couple, it’s as if you watch architecture devouring human flesh.

The inside of Manderlay is also untrustworthy. Signature gothic, angular architecture cradles the spooky rooftop from caving in. Paintings loom over inhabitants. There is life in here, but you could swear you were in a barren wasteland. No one inside is receptive to anyone (not in any humanistic way, anyway). Being titled Mrs. de Winter feels more like a designation and not a familial sign of honour. The opening fifth of the film has some charm to it; naturally, Maxim and his loved one were swooning over one another. The rest of the film, you can forget about it. It’s like feeling suffocated, and losing all of the heat in your head.

The film is through the eyes of the unnamed woman, as if you were to experience a dead relationship through one of the partners.

That’s the appeal, though. You feel invasive, taking part in a corpse of a relationship. Rebecca feels partially like an allegory of a marriage that went south, and the mundanity of life that followed suit. On the other hand, this film is so engulfed in its own world, and it feels like a melodramatic partnership that is exactly as it should be seen. Hyperbole or not, Rebecca is effective. You’ll feel miserable in microseconds.

The film is obviously more than a pity party. We start to learn that Manderlay is a house and not a home. Everything from the darkest of corridors, to the coldest of housekeepers (Mrs. Danvers, played brilliantly by Judith Anderson) is saying the new Mrs. de Winter is not welcome. Despite all of the fond memories found earlier in the film, none of that matters when an entire establishment hates you. But, why is she despised so much? Is the world threatened by her? Is she trying to replace the dearly departed Rebecca de Winter? All she was doing was following her heart. The more she tries to continue her life, the darker her world gets. We’re talking very dark. Hitchcockian dark. A lot of this anguish leads up to one of the more shocking moments in early Best Picture history: the opportunity to face an early grave by one’s own hand. It isn’t done in a typical, good-old Hollywood kind of way either. Rebecca gets disgustingly sinister, and it’s spine tingling.

This confrontation between the new Mrs. de Winter, and Mrs. Danvers, is an unforgettably unsettling exchange.

But, alas, we have to go darker. I won’t spoil anything, but Rebecca most certainly does not hold back. I will be honest, though. You may predict the twist a mile away, and that is okay. It is 2019, after all. We have had decades of films that have touched upon similar topics since Rebecca, and I would argue the twist wasn’t entirely inventive even when it first came out. It isn’t about being caught off guard. It’s about embracing the truth, and knowing that your darkest fears can indeed come true. That’s Rebecca’s staying power. The climax is stronger than its cheap thrills, since it encourages all of your lingering worries to come to fruition. In a film this void of life, all you want is some sort of joy. Rebecca says “not today”, and it kicks you over.

I’m building this film up, it seems. By 2019’s standards, Rebecca is hardly disturbing. You have to take yourself back to 1940, though. Suppose someone avoided horrors, mysteries, thrillers, or anything evil in nature. Rebecca wins best picture. Miraculously, some movie house is fortunate enough to be playing it again (not quite how the ‘40s worked, but I’m just saying). You’ve always been curious to finally see how this won Best Picture You sit in the theatre, and you were so moved by Our Town. Then, this comes up. This film beat out The Grapes of Wrath, The Great Dictator, The Philadelphia Story, and other classics of the ‘40s. To this day, I am astonished as to how it won, but I am glad (and I love every single one of the previously mentioned films, even enough to rate them perfect scores). This is a very bold early Best Picture win. Believe it or not, it’s also the only Alfred Hitchcock film to win Best Picture. You read that correctly.

Maxim de Winter deteriorates from an object of affection, into a soulless husk with dead eyes by Rebecca’s end.

The Academy was back to its safer ways one year later, when How Green was My Valley beat Citizen Kane (more on that tomorrow), but it’s nice when the Oscars just surprise you like this. It’s tough to even rate this amongst Hitchcock’s own films. Rebecca isn’t Vertigo, Rear Window, Psycho or Strangers on a Train, but it’s Rebecca. A number of Hitchcock purists may dismiss this film, especially because its nature may seem self aggrandizing. There’s also the insistence that this is more of a David O. Selznick picture (which, let’s be fair, it kind of is in ways). There are some of us that adore this film, and I am most definitely a part of this group. Rebecca was an unforgettable experience ten minutes in. It only gestated into being the staring contest with demise that I remember it as from that first viewing on. With every revisit to Manderlay, I feel like I am tempting fate. Not many early films capture the dimmest signs of life like Rebecca does, and it still is impactful so many years later.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.