Gentleman's Agreement

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Gentleman’s Agreement is the twentieth Best Picture winner at the 1947 Academy Awards.

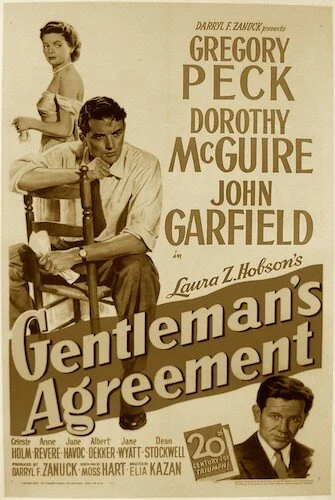

Elia Kazan would go on to direct On The Waterfront seven years from now. It’s a drama that speaks for all of the blue collared workers that have ever been limited to less than nothing by authoritative greed. It would end up being his opus. A few years earlier, Kazan won Best Picture for another film: a much less discussed work, at that. In fact, if it wasn’t just recently submitted into the National Film Registry, most of the people even talking about this film are Oscar nuts like myself. Gentleman’s Agreement was a similar mission (to bring light to oppressed voices), and I would argue it’s vastly underrated. Gregory Peck commands the majority of the film as journalist Philip Green, who goes undercover as a converted Jew to write a report on anti-Semitic bigotry in New York City.

What I love the most about this film, is how it takes its time to even arrive to this synopsis. We don’t see Green come up with this idea (or even begin to pull it off) until at least a quarter into the film (or so it feels). We learn to understand Green as a person (a widowed father with nothing to lose), his surroundings (a tainted city), and his reasons. If The Lost Weekend wanted to discuss alcohol abuse after prohibition, and The Best Years of Our Lives shed light on the return home for traumatized veterans, Gentleman’s Agreement is the third Best Picture winner in a row to tackle a then-current discovery stemming from historical shifting. World War II may have been long finished, but an embedded hatred for marginalized people (in this case, the Jewish community) wasn’t necessarily going anywhere. This was Kazan’s means of wrapping his head around that difficult reality.

Green coming to the realization that this was an important assignment to fulfil.

As you can expect, things get dicier the deeper Green goes into his assignment. Right away, many heads turned and saw Green differently, as he proclaims himself to be Jewish (despite not actually having converted). For me, it’s the little details that sell this story. Every background reaction adds authenticity to the experience. Sometimes, facing anti-Semites head on is hard enough. Sometimes, it’s the background chatter, where you aren’t even worth talking to, that becomes too much. Should you face every bigot? Why should anyone even have to deal with this at all? With Green, his experiment translates into an everyday struggle that millions of people worldwide have to face. Even his closest loved ones don’t see him the same way anymore. It’s not a challenging film by any means (perhaps why it has received lower scoring than it should on popular film websites), but that doesn’t make it any less important.

My only major gripe is the very bitter end, which was tacked on to satisfy the usual culprits (the Hayes code’s policies). It’s exceptionally stiff, and it stymies the flow of an otherwise profound conclusion. If you can ignore the final thirty seconds or so (you can even eject your disc prematurely), then Gentleman’s Agreement is a discussion whose priorities are mostly just. Many films have had these types of discussions since, and Gentleman’s Agreement wasn’t the first to tackle them at all (Crossfire came out that same year, although it replaced its homosexuality conversation with a similar anti-semite dilemma). It’s still a good-enough jab at these kinds of issues, and a Best Picture win that made perfect sense for its time. There are better Kazan films and Best Picture winners, but Gentleman’s Agreement is still sorely forgotten about.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.