The Apartment

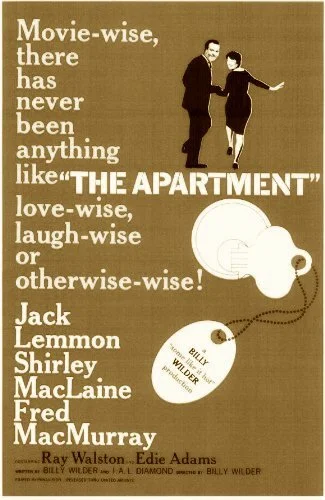

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Apartment is the thirty third Best Picture winner at the 1960 Academy Awards.

Amongst all of the classic films Billy Wilder made, there are a few particular standouts. Sunset Boulevard is his all around opus, especially in regards to its love-hate relationship with Hollywood. Double Indemnity is a staple noir statement that never quite got topped. Some Like it Hot was one of the last great screwball set ups. From there on out, we can get into particulates, and subjective selections: a must-do for another day to celebrate the works of Wilder.

One film compartmentalized many of Wilder's classic tropes, and it ended up being his second Best Picture winner The Apartment. It unloads the laughs, sadness, existential darkness, and calamity of every top Wilder film, with precise cohesion. It almost feels like a greatest hits reel of his most talented types of writing (with help from frequent collaborator I. A. L. Diamond, of course). Within it's two hour duration, you will go through all of the motions that Bud Baxter experiences empathetically.

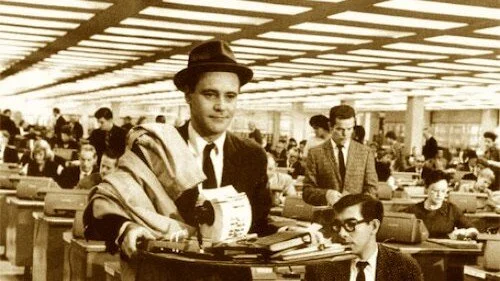

Bud having to deal with the limbo known as “work”.

Bud is a pushover that lets life dictate all of his moves: what his career is, who can use his own living quarters for their own reasons, and who he can associate with. He tries to let all of these outside forces correlate for his own benefit: why doesn't he allow higher ups in his company use his apartment to commit private affairs, while he gets in their good books and then gets promoted? He gets sick from being outside (since he can't go home like he wishes), but who cares when this is all in the name of job security?

When Bud falls in love with the elevator operator Fran, that's it. He wants change. He knows he deserves a better life than what he has. However, he continues to let others push his buttons, and even falls into a deep depression. Little does he know that Fran is just as manipulated and stuck as he is. They crossed paths because they were following the courses others demanded them to take. It was bound to happen.

A shattered self-reflection. A realization of the fragmented and underutilized now.

The Apartment is far from afraid of the darkness that mental health issues can turn to. As charming and fluffy as the earlier moments are, much of the second and third acts are incredibly grim. Wilder had to go to these places, and The Apartment benefits from these choices. Otherwise, the brevity of someone who lets society yank them around can't be felt. The message has to be clear: you can hit rock bottom if you don't look out for yourself. You can lose sight of what is yours if others take ownership, whether it be your job, your apartment, or your own life.

The actual apartment plays its own character in a strange way. It is the walls containing infidelity, like a threatened witness blackmailed into not telling. When Bud tries to reclaim this space as his own, it almost feels like the apartment is wounded and in need of help: messes need to be cleaned, and stuffiness needs to be let out. This apartment is where Bud lives, but everyone else (with their own homes, I might add) lives in it themselves. This apartment is an apartment, because it represents perceived individuality, and distances itself from being a home that can be broken by lies and mistrust.

The monotony created by the repetition of desks sets a tone of despair in The Apartment.

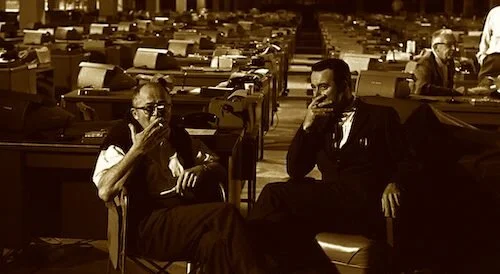

To lead the show, Jack Lemmon and Shirley Maclaine are the best they have ever been in this film. Both are funny, enigmatic, and saddening. Both make detrimental moves out of feeling cornered to do so. Both destroy themselves, as an attempt to get out of their predicaments. Following either tale of self sabotage is due to depress you, because nice people don't deserve to finish last. It is rough to see both characters receive each blow, and how their souls take a toll again and again and again.

Bud and Fran finally dealing their own cards, rather than working with what they’re dealt.

The Apartment shows promise; with determination, self care, and a little bit of patience, any stunting situation can be worked out of. We see enough romantic dramas or comedies, where a person is trying to change or better the other person. Part of The Apartment's entire message from the beginning is how that same level of care has to be applied to ourselves. Bud tidies his place, but not his mind. Fran gets others where they need to go on the elevator, but not herself. Together, with the use of an elevator that can go up to a apartment, both souls can get each other where they needed to be; they had to see their worth in themselves to do so. Wilder doesn't mind getting dark, because The Apartment's resolution is undeniably fulfilling.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.