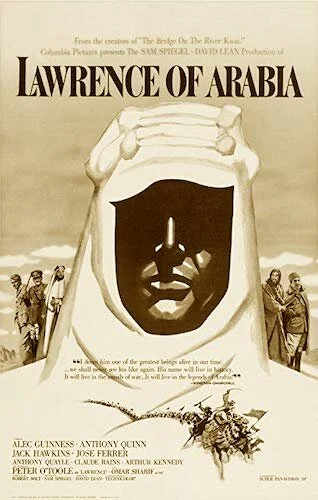

Lawrence of Arabia

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Lawrence of Arabia is the thirty fifth Best Picture winner at the 1962 Academy Awards.

In 1957, David Lean helped push what a historical epic could be with The Bridge on the River Kwai. The scope of the film framed the large base, the feuding personalities, and the countless amounts of motives going on at once. That was the perceived level of perfection that an epic film could fulfill for that era. Shortly after, Lean bested himself. Other films caught up to Kwai, but there came a film that not even Lean could match. To this day, the follow up film Lawrence Of Arabia remains, perhaps, the zenith of all cinematic epics: a technical display of directing prowess, with every single element being the utmost best that they can be. While a completely different beast to Kwai, Arabia acted as an enhancement on many fronts. Kwai is a gem in its own right, because of how it captured chaos. Arabia channeled political and personal evolution through similar set ups, only they were downright perfected this time around.

Before Arabia, I honestly don’t believe cinema had ever seen a better form of character development than the title role of T.E. Lawrence (dubbed “El Aurens” and other variations by his Arabian compatriots). A then-unknown Peter O’Toole — essentially billed last as an “introducing” credit — was hired for his ability to perform buffoonish humour, whilst unleashing his theatrical capabilities at will. Instead of going with a well-established star, Lean and producer Sam Spiegel opted for the riskier option of finding a new talent to lead this four hour journey. What we got was arguably the finest performance in any Best Picture winner ever, and debatably the greatest performance of all time (one of my own personal favourites, as well). It was essential to making Arabia work.

The bar scene back at the British base is one of the finest acted scenes in film history.

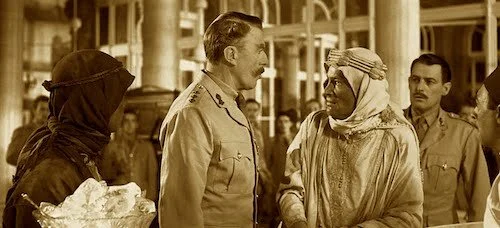

O’Toole begins Arabia as a clumsy, distracted loner: a cartographer that no one really gets along with, because of his quirks. He purposefully burns himself with flames, ignores people to discuss artwork, and walks around so stiffly. This is our leader, folks. We know there will be a tweak to his image very soon, because we start the film off at the time of Lawrence’s death. We also quickly find out how polarizing he is, as he is both crowned a hero and a monster within the same crowds. Back to the original state of Lawrence. We can easily see why his early qualifications may be dubious.

Alas, he is sent on a mission to find Prince Faisal of Syria, during the World War I Arab Revolt movement. From that moment on, we slowly see Lawrence shift. He talks to his own echoes in the vast deserts. He loves his new items of clothing gifted to him. Gradually, this spark begins to fade. It turns into power. As Arabia moves along, Lawrence himself becomes more confident, but his eccentricities become callousnesses. There was nothing wrong putting T. E. Lawrence on this mission, but ensuring one person is in charge of so much is destined to mutate them for life. This is where the controversy comes from.

T. E. Lawrence when he was still a curious misfit.

Well, there are also the horrors of war that Lawrence succumbed to. Seeing the death of the innocent, the mass amounts of bloodshed, and having been a survivor of military torture himself, Lawrence also began to fade, because he realized just how bad the world was. His demand for leadership is his means of trying to rectify his surroundings. Again, this can lead to carelessness, but in Lawrence’s mind, this was all for the greater good. War changes someone, and Lawrence of Arabia is the documentation of the many ways T. E. Lawrence was affected (and how this affected the British-Arab connection during the war).

O’Toole never leaps right into a commanding role. He matches the pacing of the film, and all of his turns feel genuine. As he hits each particular beat, you can sense how each moment acts as an attribute to his final character. The screenplay by Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson is also noteworthy for this impeccable development, as it is through the patience found within the text that Arabia is able to take each proper step. Together, Lawrence is channeled effectively, and we can discern how we feel about him without any conflicting biases, forced depictions, or lazy progressions.

F.A. Young’s photography was another major selling point for Lawrence of Arabia.

Once the proper lead actor was found, Lean could toss in everything he learned from The Bridge on the River Kwai and apply it here. The expansive settings are back. This time, a bridge is replaced with endless sand dunes, train tracks, and check point bases. Maurice Jarre’s score (which also bookmarked the film with an overture and an intermission segue) sets the tone exactly so. His compositions are triumphant, exhilarating, but also curious, like a newly found guide paving the way for others, and discovering a new world for himself. F. A. Young’s cinematography balanced the bright sand and the bluest of skies (and the deepest sunrises and sunsets in between). As Lawrence traverses the Nefud Desert, and coasts into Aqaba (amongst other missions), you feel as though you are placed in these scenarios yourself.

A number of Lean veterans were tossed into the mix as well, once again showcasing his expansion of his common ground. Alec Guinness has a much smaller part here, this time as Prince Faisal himself. Jack Hawkins returns as well, as General Allenby. However, like O’Toole, there are some new faces here too (either in general, or concerning Lean’s filmography). Omar Sharif was the major supporting role in the film: Sherif Ali. An enemy-turned-ally for Lawrence, Ali is another highly complex character that goes through the motions throughout the film. Anthony Quinn played Auda abu Tayi: a major foil character to Ali, who leads a similar relationship with Lawrence. All of these conflicting forces only add to Lawrence’s tough decision making, and not a single performer feels out of place or lazy.

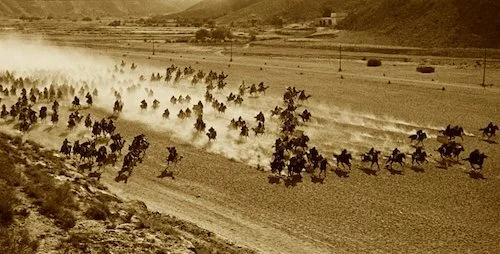

David Lean’s direction remains unmatched, especially in an industry now driven by CGI.

To make all of this work, Lean had to pull out all the stops, with one of the best cases for filmmaking you may ever find. Yes, he had a lot of help, considering the acting, the editing, the cinematography, the music, and the everything else. He could have let all of these factors pull their own weight. He didn’t. Arabia boasts some of cinema’s strongest direction, particularly the combat sequences, with countless camel and horse driving warriors charging into cities or landscapes. These long, swooping shots feel nearly impossible to pull off today, especially considering how many studios and filmmakers would rely on computer generated effects to get by.

Not a single second feels useless in Lawrence of Arabia. Not one. It’s nearly four hours, and every single moment feels right. The four minutes of darkness with only music to open the film? Keep them. The motorcycle accident that feels hokey, but is the first image we see? Love it. This is a rare case where I would not change one iota, especially the ambiguity. We are left to decide how we feel about any part of the film. We end with opposing sides bickering, having resolved nothing. So much happens, and some things remain as they were. Lawrence’s journey ends with him sent off without a perfect resolution, as he eyeballs his next thrilling escape: motorcycle riding. Not once does Arabia hold your hand.

The practical effects are still jaw dropping.

David Lean mastered the middle ground in a Hollywood juggernaut, during a time where most filmmakers felt forced into having their films hold you along the ride. Lawrence of Arabia, like its title character, plays by its own rules and does anything to get the job done. Unlike T. E. Lawrence (as shown in the film), Lawrence of Arabia appears to have made every correct decision. It signified the future of films far ahead to the point that cinema itself just turned back. Effects changed. Shooting was different. Filmmaking reached a crossroad, where it slinked into new methods and means. The films created like Lawrence of Arabia were no more, thus it remains the best of its kind. Even David Lean’s subsequent — and notable— efforts paled in comparison. Lawrence of Arabia is a one-in-a-million effort, where any differences would have tampered with the final result. Every separate piece is a highlight in filmmaking, so Lawrence of Arabia remains a benchmark moment in an always-changing industry.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.