My Fair Lady

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. My Fair Lady is the thirty seventh Best Picture winner at the 1964 Academy Awards.

I firmly believe that everyone has that one musical in their heart that has the healing power to make every problem of yours temporarily disappear. I'm talking the typical show stopping musicals that act as an escape but are only profound to some degree. For me, this is George Cuckor's My Fair Lady: a three hour departure from the woes of life, while also being an interesting statement on music's relation to the science of the human voice, and commentary on the double standards of societal gazes (particularly from the upper class, and men's unrealistic expectations of women). All I know is that I get sucked in to this theatrical world every single time I watch it.

So we follow the experiment Professor Henry Higgins performs on Eliza Doolittle: a poor flower girl from off the street. Higgins cannot stand the sound of her voice. Because of his ego, and his want to boast about how important he is to the life of another (particularly a woman he deems unworthy), he vows to turn her into a socialite that can fool the highest of the elite of England. Right away, I side with Doolittle, who has only been treated kindly (cleaned, fed, sheltered) for a stupid, one-sided bet. Despite this, Doolittle does not want to be turned into a lab rat (gee, I wonder why).

Eliza Doolittle begins the film as a Cockney flower girl from the street, used as a pawn in a pompous professor’s self entitled bet.

The mirroring of phonetics coaching and music makes My Fair Lady an instantly recognizable film for me. Comparing this to Gigi (the other film based on Pygmalion), we can see that the toxic standards of powerful men is not necessarily rewarded here, unlike in the Vincente Minnelli film six years prior. We are happy that Doolittle is doing well, not that Higgins is winning his wager. Because Cuckor (and the screenplay by one of the stage production creators Alan Jay Lerner), we see more of Doolittle’s life as a person: her struggles, her connection with her father, and why this experiment can actually benefit her, even though that isn’t Higgins’ intention.

So, Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle belts out an obnoxious drawl, to create cacophony amongst the film’s tender songs. Even though she herself can sing (see Funny Face), most of her songs were dubbed by Marni Nixon; outside of the number “Just You Wait”, and some leaked outtakes online, this decision results in a major “what if” surrounding the marriage between Doolittle as a speaker and as a singer. Either way, the dubbing is hardly noticeable if you didn’t know it was there, so the point still comes across. Doolittle begins her singing by punctuating her words like a percussive instrument: a chaotic pulse that still manages to get by despite its intrusions.

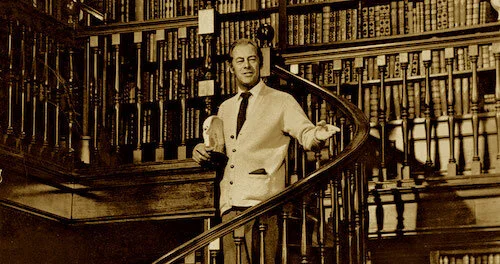

Henry Higgins, being the chuffed narcissist that he is.

Henry Higgins is reprised by Rex Harrison, who also played the professor in the original stage version of My Fair Lady. Even though he isn’t with his original Eliza Doolittle (Julie Andrews), he is able to turn his despicable arrogance into fluid on-screen chemistry, especially with Hepburn. When he gets proud of himself, Doolittle gets proud of herself. Their combatting missions still result in shared successes, and it makes for an interesting contrast. So, Eliza Doolittle is starting to annunciate better, and speak with a softer tone. Great! Whose separate mission will be fulfilled first? Higgins with his showcasing of his capabilities, or Doolittle with a better life for herself?

My Fair Lady is also very aware that it is a theatrical adaptation. It functions similarly to West Side Story of a few years earlier, but with less reliance on that feature, and more magic created in fewer moments. This includes a one-off sequence, of townspeople stopping their errands in their tracks on cue, as if they were creating tableaus on stage. On the big screen, this feels like an establishment of the many individual stories happening in London on a day like this. As the film has strength in all of its departments, these surprise decisions don’t hinder the film in any way (like they did in Gigi, where each move felt out of place in an otherwise bland feature).

Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins feuding.

When we reach the third act of the film, and Doolittle is now a transformed character (with the odd slip back to her roots), My Fair Lady similarly takes on a completely different tone, as if it too is trying its best to appear regal. Outside of the horse track scene, the illusion begins to blur into reality. Doolittle truly is a different person, whether it be for her own sake or for Higgins’ bragging rights. Seeing her ability to depart from him is a fantastic moment, when someone recognizes she is not an object, but a human being with all of the rights she is deserving of. My Fair Lady begins to straighten its back, and walk more confidently. It is no longer the slightly silly musical of the first two hours.

We end off with a highly divisive scene; one that seems to leave a sour taste in the mouths of even fans. Doolittle and Higgins agree to stay in each others lives, and she is fine with fetching his slippers. For many, this is two steps backwards: a free woman feeling okay with being treated as a servant by the man that ignored her true wishes for the majority of three hours. For me, it signals a hopeful future, of a now-commanding Doolittle having to brush Higgins up, and turn him into an upstanding individual. She is okay — for now — because this is going to be a lengthy process. She is more understanding than he is, having been in the same position before. Maybe a more definitive revelation of this mutual agreement wouldn’t have hurt, but I see this scene going either way.

Doolittle after her transformation: she blends in with the rest of the upper class folk around her.

Within its long-enough time frame, My Fair Lady coasts through so many sensations and moods. As I said before, there is at least one musical that everyone holds dear to their hearts; a portal into the minds of musical fanatics, and what they experience with the genre as a whole. While I love a good musical (Singin’ in the Rain is the best place to start), My Fair Lady feels like the archetypal, theatrical musical that defines the genre in a nutshell, and is my personal example. The merging of dialogue, music, and vocal training never ceases to spellbind me. The gradual tonal shift of the film is similarly hypnotic. It can’t get any better than turning tongue twisters and vocal warmups into songs (well, Singin’ in the Rain did that too, but I digress) when it comes to this narrative. My Fair Lady is as extravagant as it is elegant. As sensational as it is silly. As lush as it is “loverly”.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.