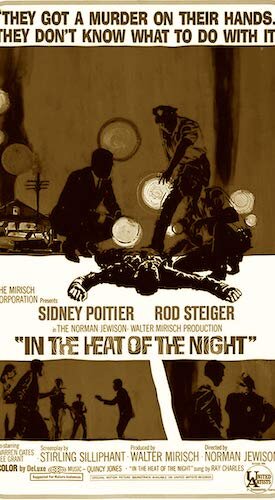

In the Heat of the Night

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. In the Heat of the Night is the fortieth Best Picture winner at the 1967 Academy Awards.

Take a good look at the 1967 batch of Best Picture nominees. Really have a good stare at these five films.

Guess Who's Coming to Dinner

Bonnie and Clyde

The Graduate

Dr. Dolittle

In the Heat of the Night

Outside of the outrageously mediocre Dr. Dolittle (which was only given the time of day thanks to shameless promoting and campaigning), we have four other films that squashed the hopes and dreams of the stale Old Hollywood, and the filmmakers that got by on schmaltz. The Graduate (which earned Mike Nichols a Best Director win) is a taboo coming-of-age film featuring the grooming of a naive student. Guess Who's Coming to Dinner was an uncomfortable confrontation with prejudice, done in comedic fashion. Bonnie and Clyde (the best film of the batch) was arguably a B-picture that spat all over the Hayes Code, and remains a relentlessly rebellious film now.

In the Heat of the Night confronts tensions between a marginalized detective, and a highly racist community (including the evolution of his bigoted partner chief Gillespie).

The winner was In the Heat of the Night: arguably the most drastic shift in a Best Picture winner the Academy had seen at that point. Norman Jewison's neo-noir mystery felt like a combination of the previous three films (we are disregarding Dr. Dolittle's existence for the rest of the review). It features Sidney Poitier in a narrative that reveals the depths that racists are willing to go (Guess Who). It also has a variety of filmmaking techniques meant to deviate away from traditional measures (The Graduate). It lastly was as visceral and raw as Bonnie and Clyde, with a refusal to brush any detail under the rug.

In the Heat of the Night succeeds in all ways, by refusing to sugar coat any of the bigotry detective Virgil Tibbs has to face, all while decimating the clean Hollywood regulations that goody two shoe films had to abide by. Even the music -- by Quincy Jones -- takes on some drastic liberties, including unconventional percussive sounds to disorient a chase scene. Maybe not every single decision makes perfect sense in 2019, but consider how most of these choices still do. That's cinematic foresight. Not many mainstream films like this did as many risks, let alone have all of them age well. Heat is still an anomaly.

In the Heat of the Night excels at shifting gazes, from officers and criminals, to racists and an African American detective, as Tibbs is unnecessarily treated the same way as the film’s thugs are.

Heat pits Tibbs and police chief Gillespie (Rod Steiger) together for the entire film. Gillespie smacks away at his gum, because he has the liberty of speaking and shutting up whenever he wants to. Tibbs (Poitier) is forced to speak to defend himself, and yet is never listened to due to his race. Gillespie starts the film running the show, while Tibbs is immediately targeted for being a suspect, despite him only coming to Mississippi to lead the impending murder case. These many turnarounds make Heat interesting. How many ways can Jewison make the scenarios featured on screen get sidetracked by racism? Apparently, he pulled this off in numerous cases.

The fixation of a dead corpse at a crime scene is filmed the same way a marginalized person is stared at by racists: with the utmost scrutiny. Extreme close ups and smooth zooms and pans turn Heat into a series of examinations, through various sets of eyes. The tension gets dialled up to eleven rather quickly, and you can be certain that Heat is going to burst at any time. It does, and it does so frequently. Jewison doesn't view a discussion on intolerance as a gambit, but rather a necessity, not to be kept for special moments. The entire film is a message to the public; why use real world struggles as a gimmick? In a film that boldly takes on a series of unorthodox choices, it's this kind of restraint that renders Heat a wise film.

Another powerful dynamic is seeing how the Mississippi town operates differently than Tibbs’ stomping grounds in Philadelphia, including the different perceptions on how non-whites are treated.

In the Heat of the Night was unlike any Best Picture film before it, and it signalled a major turning point in how the mainstream was perceiving the New Hollywood movement. Afterwards, Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, both Godfather films of the '70s, and other unconventional films were destined to win Best Picture next. It didn't erase safe films from winning, but it proved that edgier works had a shot at changing the general public's perceptions of cinema. If something this important and different won major awards, how much longer could these kinds of pictures be shrugged off? In the Heat of the Night is a valiant look at disgusting levels of racism, the labyrinthine ways of crime, and the important of films telling stories meant to be heard in very different ways.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.