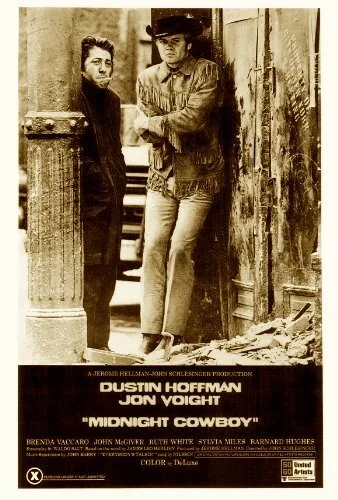

Midnight Cowboy

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Midnight Cowboy is the forty second Best Picture winner at the 1969 Academy Awards.

After that quick Oliver! detour, the Academy turned right back around, and booked it down the newly paved highway In the Heat of the Night created. It sped for miles upon miles, until it reached Midnight Cowboy: the undeniable proof that the Academy was now accepting unconventional works. Let's rewind a little bit. The Best Picture winner released in 1959 was Ben-Hur. In 1949, it was All the Kings Men. 1939, Gone With the Wind. The Broadway Melody was obviously 1929. Every other gap between each era feels like a stepping stone. Just try comparing a clean-cut, Old Hollywood staple like Ben-Hur with the rebellious Midnight Cowboy of the New Hollywood movement.

So, Ben-Hur compared the solo odyssey of one man to the tribulations of Jesus Christ. Ten years later, we have the tale of Joe Buck: a cowboy that travels to New York with the dream of becoming a male prostitute. That's what I'm talking about. John Schlesinger goes beyond this story by tossing in a number of borderline experimental decisions, like he was influenced by the kind of underground art parties, like the one featured in the film. Midnight Cowboy was amongst friends in this department, including works like Easy Rider. For the same of its Best Picture win, it's interesting to see just how off-the-rails the film is willing to go (and how it steered the Academy down the same path for at least ten years).

Joe Buck is a cowboy venturing out of the west, and into a life of prostitution: a symbol for how Old Hollywood was making the leap into new territory.

In 2019, Midnight Cowboy feels a little strange. Joe Buck and Enrico Rizzo aren't heroes by any stretch, especially with their highly problematic beliefs. I don't believe we were ever meant to root for them. Rather, I think both characters are examples of a failing society: two chasers of a dream that wounded them. From polar opposite parts of the country, they are facing similar fates. Rizzo is a warning sign for Buck: things aren't that much better here. Substituting a quiet yet uninteresting life for excitement and suffering is a silly sacrifice when observing it from afar. In Buck's position, he just wanted to have more; he ended up with less.

You're not really supporting these people, but you are interested to see where they wind up. When America gives them a hard time, how much of their issues are caused by their own ineptness? A lot, actually. Buck aspires to be a gigolo out of his fantasies: the abuse of reality because of the refusal to accept things at face value. Like the adult film industry, fictitious images are conjured up, and cloud the sincerities of human experiences. Midnight Cowboy is not the revelation of these tender moments, but the addiction of projected desires as a means of dismissing the worst aspects of life. Buck and Rizzo are beyond stumbling upon warmth. They're freezing their limbs off in their own private hellhole.

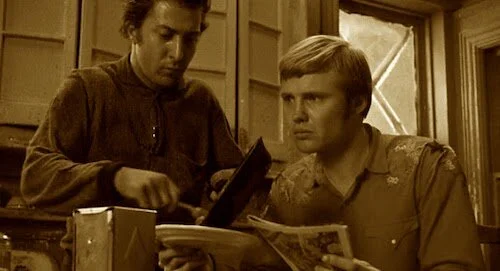

Buck and Rizzo living in an abandoned apartment, struggling to get by.

They begin to abuse others as a means of getting ahead, mainly because they were abused themselves. In fact, Rizzo starts off his relationship with Buck by conning him. There is no love found in this film (except the flashbacks in Buck's memories). Again, there is no connection to these characters worth finding for most of the film. It's the final stretch of the film, where the fading away of a person drives home the severity of this kind of situation. Seeing the only person you know drift off reminds you that dreams are temporary, and so is life. Life is to be lived, not spent driving yourself sick for some sort of aspiration. In the case of Midnight Cowboy, you're looking at the poisoning of an entire community, and of the dreamers themselves through self infliction.

Whether these awful outcomes are the result of one's own choices (Joe Buck), or of sheer back luck in an unforgiving world (Enrico Rizzo), Midnight Cowboy rubs our noses into the dirt caused by disheveled capitalism, a dog-eat-dog nation, and the monstrosities created by our own personal ambitions going up against billions of other participants with the same game plans. Ironically, Midnight Cowboy plays by its own rules, and goes against so many regulations that would have made it a commercially viable, guaranteed crowd pleaser. It's stuffed with avant-garde cuts and sequences meant to stray away from the mainstream norm. It features two highly unlikable leads. All of its graphic details are dealt with head on.

Joe Buck making an attempt with one of his clients.

Look at it now. It's the only X-rated film to win Best Picture. The film is iconic in a counter culture movement. Midnight Cowboy was enough of a moment in pop culture to be referenced and parodied endlessly. By exposing the faultiness of everyone's chasing of the American dream, Midnight Cowboy became a beacon signaling a major turning point in cinema. Majorly celebrated works can be art. Ambiguity can be analyzed on a significant level. Challenge could be the new convention. A controversial film about the ugly underside of capitalism can lead into an iconic Seinfeld episode. For 1969, Midnight Cowboy was noticeable enough to make a stink. Decades later, it’s beyond understood. Its X-rating seems a bit steep now. It is easy to reference amongst friends. Its theme song (“Everybody’s Talkin”) is still being used in spades. Outside of its characters being problematic (although that is a bit of the film’s point), Midnight Cowboy has never lost its cinematic relevancy, despite its efforts trying to destroy the cinematic codes of conduct.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.