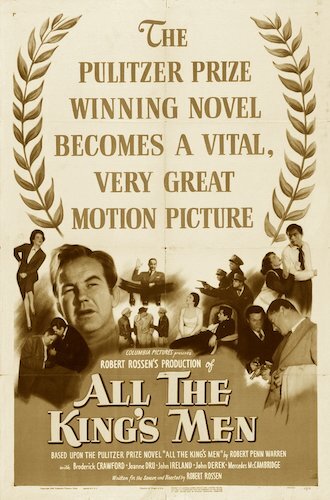

All the King's Men

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. All the King’s Men is the twenty second Best Picture winner at the 1949 Academy Awards.

Robert Penn Warren’s classic novel All the King’s Men foretold a world where almost every governed area (a town, a state, or a country) was to experience suffocating corruption. This was far from a new problem in the mid ‘40s, but it presented an ongoing problem with a solution that would only turn out to enhance the problem even more than before. This comes in the form of a concerned citizen-turned-politician that gets sucked into the game of power, and all of their promises turn into fodder for control. Named after the timely cautionary tale of Humpty Dumpty, Warren’s narrative involves a heart broken by greed, and it is never able to be mended again.

Robert Rossen came out with a cinematic adaptation of this novel a few years later. He channeled the noir genre by turning the lead character Willie Stark into a different kind of an archetypal “detective”: a community man trying to do what’s best for his people, only to get more monstrous the deeper he gets into politics. What I like about Rossen’s angle, is that you can still identify Stark as a fallen hero, but you can also understand that this may not entirely be his fault. Can you even easily change a corrupt field without getting tainted yourself? We’re at a point where industries, companies, and careers are warped enough that they are almost out of the hands of humanity. You are shaped by them, and not the other way around. Thus is the story of All the King’s Men: a martyr that meant to do good, but became the despicable image he so hated before.

The beginning of the film is concerned with Stark’s attempts to better his county.

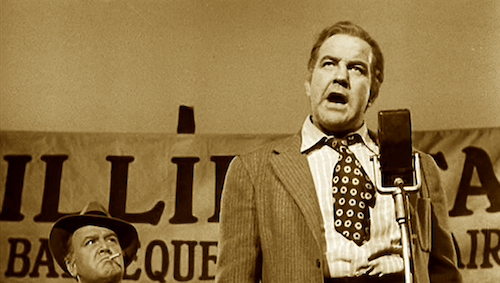

Broderick Crawford plays Stark with the type of character development that somehow predated acting innovators like Marlon Brando. You may not even notice Stark’s change of heart at first, because his transmogrification is so gradual. You’ll feel as if it’s too late, by the time you finally catch on. This is how easy it is to be misled. It’s not so difficult to judge a politician face on, but All the King’s Men is an argument that anyone can be fooled if it’s someone you know going into office. You’re good friends with this guy! How could he become the very type of goblin he is rallying against? There’s just no way.

The climax is relentlessly dark for a 'late ‘40s picture. There’s no hand holding with the content revealed, nor in the way it is presented. The first time I watched this film, I was actually stunned (especially when comparing it to the other Best Picture winners or nominees around this time). Technically, Stark is a villain, so no Hayes codes are actually broken, you could debate. Perhaps it is the popular source material that granted All the King’s Men carte blanche from being changed into a more sugary narrative. Either way, the film ends off on a bombastic note, that is only fitting with the message of heightening toxicity. A twisted leader can result in a twisted society. Chaos invites chaos. No one is a “good guy” in this intense sequence. It’s an even playing field, and it makes you think (rather than being spoon fed). It’s a great change of pace, given the year this film came out.

Stark begins to command each scene more and more, as the film continues. He shifts from being the voice of his class, to being the shouts of authoritarianism.

In 2006, Steven Zaillian gave it his own shot, by releasing his own All the King’s Men adaptation. It’s shallow, melodramatic, and imbalanced to the point of being incredulous. If anything, it should have made more of a stink in the new millennium, during the rise of social media and the dawn of conversational online forums. It tried way too hard to make a large statement. The 1949 version knows its source is strong enough, and that its message can do most of the heavy lifting. All it needed was the right Willie Stark (which it had in the form of Broderick Crawford). Everything else was left to churn on its own. It’s a much more humanistic approach, and it has aged better seventy years later than Zaillian’s attempt has in just thirteen years. Its cautions about politics, unfortunately, only get stronger as each year passes by. It’s easy to hate the figurehead of any political office, especially when the protocol will never change. The human gets blamed for the majority of a system that is beyond faulty, because it’s easier to hate a face than change how politics work.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.