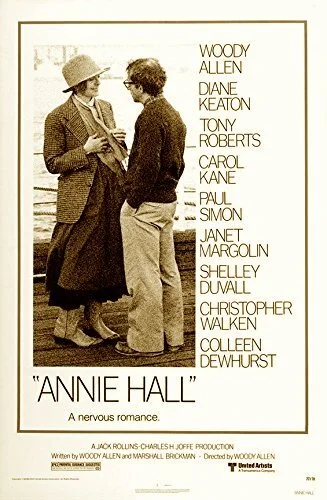

Annie Hall

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Annie Hall is the fiftieth Best Picture winner at the 1977 Academy Awards.

Never has a rom-com been like Annie Hall, before or after its release. Like the girl Alvy Singer fell in love with, Annie Hall stands out on its own as a rare irreplaceable film. Woody Allen — one of cinema’s most prolific filmmakers — was able to make a work as indescribable as the best (and most doomed) relationships we all go through. By turning this part-memoir into a series of jokes (conventional and obscure), Allen captured an experience that I honestly feel most directors barely even attempt nowadays (not when it comes to rom coms). Were ideas taken from Annie Hall since? Absolutely. Has the entire operation been ripped? Barely.

Tom Jones loved breaking the fourth wall, to cheapen the aristocratic experience. It… kind of works… somewhat. In Annie Hall, the gimmick is done so often and with so many different angles, it becomes the picking-apart of a neurotic mind. These gags are barely for our benefit; more so, they are to allow Singer to spill all of his woes onto us. We’re just lucky that we get to enjoy all of these crazy observations. Since Annie Hall is non-linear as well, these sequences never feel out of place, or forced. Each execution is a breath of fresh air, in a genre that can easily be beaten to death, and at every instance you worry Annie Hall is about to sell out.

The way Annie Hall involves the viewer makes it an even funnier tale.

In a lot of ways, Annie Hall is the wish that certain achievements could be pulled off in the real world: the reliving of certain memories, the ability to have famous directors tell academics they are dead wrong about their analyses, and the coursing through dimensions to see if life in parallel universes would be better. We’re talking about out-of-body experiences, living through a childhood with an adult lens, and even entering the animated galaxy. In every single iteration of Singer’s life, he is bitter, anxious, and his own enemy. He still bickers with Annie Hall, and nothing seems to work out. With all of his cinematic might, Singer cannot get him and Hall to work out. It’s hilarious, but also quite sad.

So, why is Singer such a pain to live with? Well, we enjoy all of his jokes (his fast, quit-witted quips), but Hall has to deal with this whining every single day. We put up with this for an hour and a half, not an eternity. We can maybe see where the initial charm came from, but we can tell through Hall’s responses as time goes on that things are not as lovely as they appear when you first fall in love. Sometimes, our favourite parts of a person become their vices. The magic wears off. With Annie Hall being shown out of order, we don’t get a chance to see her slowly fall out of love. We just know she does, and we are reminded that there was a time she was in love with Singer to begin with.

The many sidesteps Annie Hall takes are miniature worlds of their own, including this brief excursion into an animated depiction of Singer and Hall.

As funny as Annie Hall is, it’s not just about receiving these moments of hilarity. It’s about the clarity as well. Not many works capture the butterflies and nausea created by adoration and heartbreak. We dip outside of the possibilities of the real world often (the thoughts of each character being subtitled is a gift we all wish we had). Sometimes, it’s just about experiencing memories. The first time Singer heard Hall say “La-dee-da” and be her quirky self. The uncut moment of Hall singing to a crowd on stage. The time when Hall moved on and had herself a new partner. A lot of these experiences are left as is. We don’t need Singer’s angst to crowd these scenes. Even Singer himself knows this.

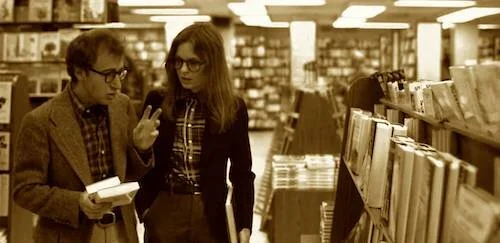

This all leads up to one of my all time favourite scenes: the lobster sequence. I didn’t get it on a first watch, as a freshman in film school. I liked the scene, but why was everybody talking about it? Unlike some other films that have grown on me the more I study cinema, Annie Hall was about life experience. Once I had had a few relationships, and have now secured myself with a loving partner for over five years at this point, a scene like the lobster scene just makes more sense to me now. Whether it was remembering the good in a bad relationship, or knowing why I was happy with my parter now, it all came together. This is an unfiltered moment in Singer’s life where he and Hall were at their happiest. His fears and her spontinaiety all came together while they were trying to cook lobsters. They were having a tough time, but they made the most of it. This is it. This is a memory untainted. This is the kind of thought that only makes sense to Singer. Why would he want to cling onto this image of him and Hall cooking lobsters? We all have our own memories that make little sense. It makes us human.

The lobster scene remains one of the finest in the history of romantic comedies: an encapsulation of the enigmatic events that can happen when two partners are happy and experiencing the oddities of life together.

As we all know, Annie Hall is quite depressing as well. We end the film with a quote only Woody Allen could turn into a piece of prose: the chicken joke. Singer can’t think outside of punchlines. It’s all he knows. So, he wraps his head around his separation as best as he can: by comparing the memories he has with Hall with batches of eggs. Even bad eggs are a part of the batch. It’s those good eggs we wait on. According to Allen, we date for the memories, even if we wind up being hurt in the end. As a result, we get a mental moving picture like Annie Hall to hold in our cerebrums for eternity. Even on our death bed, we relate to memories to live our final breaths.

Annie Hall is Singer’s attempt to salvage the good moments of a bad relationship (and, perhaps, Allen’s own mission, given his history with Diane Keaton). Keaton shines better than ever before here. Most of that comes from her own ability to inhabit the characteristics of a living, breathing puzzle of a human being. Part of that comes from Allen letting her steal every single moment that she is on screen. It’s the right thing to do, in a film where the images and sounds of a former lover make up the entire premise. To make up for these substitutions, Singer talks to us, like we’re his shrink or best friend. We’re neither, but we’re willing to listen to see why he loves Annie Hall.

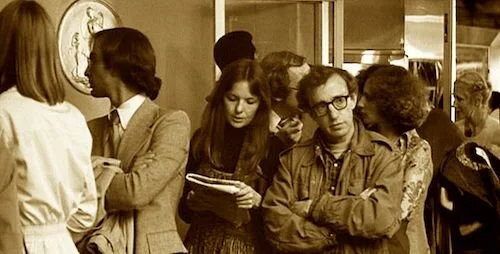

The positive and negative moments between Singer and Hall are all of the pieces of the film.

It’s strange to see where Annie Hall ended up amongst the Best Picture lore. It’s the fiftieth film to win it at the Academy Awards. From there on, we haven’t had many straight-up comedies win. If anything, Annie Hall is proof that you can’t just wing it as a comedy to get a Best Picture award. We’re past the halfway point so far, as well. We don’t have one hundred winners yet (although that milestone will be reached in a short amount of time). Comparing Annie Hall with some of the earlier comedic winners (You Can’t Take It With You, for instance) shows just how much cinema has changed, even at this point. Looking back at the film now, not even Woody Allen himself has pulled off a film even remotely similar. Annie Hall is the product of a shattered heart that needed all possibilities to mend, and the best results were committed to film. The best tragedies can be comedies if skewed enough, and so Annie Hall is a riot for all, and a disaster for Alvy Singer.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.