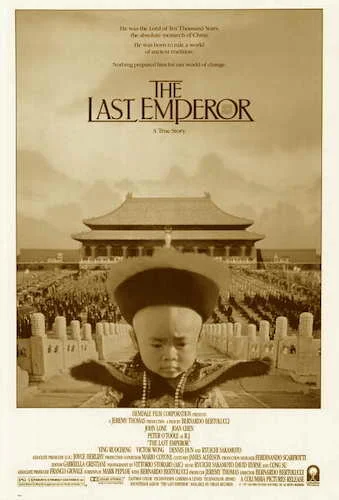

The Last Emperor

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Last Emperor is the sixtieth Best Picture winner at the 1987 Academy Awards.

Never has a film this arthouse won Best Picture before, or since. Like the main character Puyi, The Last Emperor is highly idiosyncratic in the Academy Awards canon. It feels so unusual to even be where it is, but alas it is the sixtieth Best Picture winner. It barely dictated what films would come after it, and it hardly reflected which films won in the earlier years. Puyi was — as the film’s title mentions — the last emperor of the Forbidden City in China. He lived in an enclosed civilization, tucked away from the rest of the world and hanging on to the ways of the old. As an adult, Puyi finds himself out in the open, and taking in all of the conflicting political sides, particularly in an era when China was turning into a Communist nation. He does not affect the history of the Forbidden City (outside of being the last ruler of it), and he leaves no mark on the societal changes of the world he has now entered.

Rarely does the Academy go hog wild over a film with any semblances of arthouse, let alone crown the film the greatest of the year. Would Bernardo Bertolucci’s legacy have anything to do with this? Who knows, but the end result for The Last Emperor is still an out-there affair. Bertolucci holds no punches with what we see, probably because he wasn’t trying to make an Oscar winner here. In the Forbidden City, Puyi oversees ceremonial eunuchs, maids that follow him around to collect his excrement, and his practices with concubines. That alone makes The Last Emperor a highly daring pick for Best Picture; none of Puyi’s history gets sugar coated. What turns The Last Emperor into an even more magnificent film, and a riskier Best Picture winner, is how well it strays into different moments in history without ever feeling too ambitious, or poorly balanced.

Puyi is crowned an emperor at an exceptionally young age, considering he is to hold the remains of a fading society.

The Last Emperor leaps through time, and not every moment is featured in chronological order. If anything, we start the film off with a fifty year old (or so) Puyi trying to commit suicide while in prison; this is in 1950, well after Puyi’s reign in the Forbidden City had come to an end. We bounce between Puyi’s childhood and adolescent years in a hidden, artifactual civilization, and his integration into various movements as an adult (including the invasion of Manchuria by the Japanese, the rise of the Communist Party of China, and World War II). These moments in time clash with one another, and the drastically different sides of politics turn The Last Emperor into more than just a biopic. These are coursing rivers all zipping past each other, spilling some of themselves into the same bank. I still have no idea how The Last Emperor remains uniform, because it honestly shouldn’t.

Amongst the many events happening in The Last Emperor, there is one steady notion: Puyi representing the lack of freedom. As a child, he was thrust into power, and you’d imagine that this would render him truly free. Not so. He had an entire society to be in charge of, all while being secluded from China outside of these walls. Puyi even likens the Forbidden City to a prison at an older age, and yet it is one he is still anxious to leave, because he knows nothing else. Eventually, he becomes an individual of the world, and he experiences the strangleholds of war and political turmoil, including the repercussions of not thinking the way a higher power wants him to think. The mission throughout becomes an effort for Puyi to see if any part of life, for any citizen of any system, truly can experience freedom. As royalty, a prisoner of war, or a neglected stranger, Puyi faces the same damnation everywhere.

An older Puyi telling his story as a testimony.

The one small gripe I have is that everyone in this film speaks English. It was a major adjustment I needed to make the first time I watched The Last Emperor, because everything else is so authentically detailed. It just seemed almost silly that all of the characters here spoke entirely in English (including Reginald Johnston, who was a Scotsman who spoke English, but was fluent in Mandarin). Only Puyi and Johnston, according to records, conversed with one another in English, as Johnston tutored the emperor while he was in power (and was one of the rare instances of a foreigner being allowed into the Forbidden City). Otherwise, Mandarin was the language of those that resided in the Forbidden City. While jarring at first, I’m not sure how many times I’ve watched The Last Emperor, so I suppose that artistic choice hasn’t hindered my love for the film all too much.

It’s only because of the rest of the film’s accuracy that I even notice the large amounts of English to this degree. For crying out loud, this is the first non-Chinese film to be granted access to be shot in the actual Forbidden City. Then we have all of the intricate costumes, the nuanced sets of locations outside of the City, and the large amounts of different makeup styles used for Chinese commoners, the political elite, and all of those residents during Puyi’s reign. That is a vast amount of complicated, demanding elements to pinpoint. With that said, every single image in The Last Emperor is frame-worthy, and not a single second of this near-three hour opus is wasted.

With the slight arthouse angle that The Last Emperor takes, this biographical tale becomes a sweeping, spiritual-political masterpiece.

How could a film look bad with the legendary Vittorio Storaro behind the camera? It’s simply impossible. You may know his work on Apocalypse, Now or Reds (amongst many other films). Please let The Last Emperor into your life. The cinematography is one of the very best you will find in any Best Picture winner, perhaps ever. When Storaro isn’t setting up breathtaking artistic shots, he’s conveying visual movement through even the more dialogue heavy scenes. Not one moment feels glossed over. The colour palettes for the different stages of Puyi’s life also make a major difference. His youth is full of burning yellows and deep reds. His entrance into ‘20s China is met with olives, obsidians and pearls. Grey enters the mix during the ‘40s. During Puyi’s later years in the ‘60s, all is let go. There is a balance even in the colour schemes. No more need to cling onto a moment in time.

The score is a more collaborative effort, stemming mostly from Ryuichi Sakamoto’s bold exploration of varying musical styles (including the implementation of ancestral instruments). He is joined by classical composer Cong Su, and new wave legend David Byrne (known for his solo work, or for being a member of Talking Heads). The three different universes collide here for a score that is as textbook as it is explorative. Moments intend on gripping you right away (string sections pulsating away), while others go a more experimental route (ethereal synths mixed with ancient strings being plucked, or percussive instruments of old and new). This concoction manages to fit Bertolucci’s blend of visual artistry and historical focus, as an ‘80s fixation on this tale of yesteryear becomes a reality through each and every song.

The Last Emperor is a highly artistic film, through and through.

When I sought out every Best Picture winner years ago, I was hoping for more films like The Last Emperor. I say that, meaning I had already seen this film before my experiment. I longed for awarded films that unfortunately have been lost in time, for whatever reason. Look. I know The Last Emperor still isn’t everyone’s favourite film ever, as contemporary critics either adore it (like I do) or find the film a bit of a mess (I don’t see how). I’ll go on record and say it is beyond the most underrated Best Picture winner ever. It remains a staple in Bernardo Bertolucci’s stellar filmography (and that is saying a lot), and one of the Academy’s most significant steps outside of its comfort zone. The Last Emperor is endless in its spiritual scope, its creative ambitions, and its depictions of differing civilizations through varying eras. For the aspirations alone, The Last Emperor demands your attention. Who knows. You may find yourself like me, wondering where the love for this film is.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.