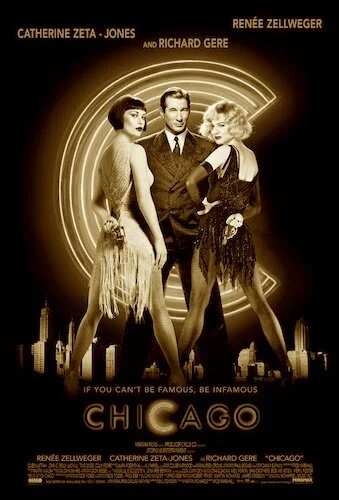

Chicago

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Chicago is the seventy fifth Best Picture winner at the 2002 Academy Awards.

Believe it or not, Chicago was the last Best Picture winner I watched when originally going through every single past winner (this, of course, excludes the current entires that are happening one at a time). Back in 2015, I had blazed through all of the past Best Pictures that I had not seen, and even revisited most of the films that I was already familiar with. Chicago was that final picture: I was twelve when the Rob Marshall interpretation came out. Now, I am highly familiar with Bob Fosse’s works. All That Jazz is a personal favourite of mine in the musical genre (top ten material), and Cabaret is brilliant in its own right. Chicago is likely what he is best known for, especially since Marshall’s resurrection of the ‘20s crime musical is still fresh in the minds of many. This is because Chicago is a major catalyst of this major revival of the good old fashioned musical; it remains the last musical to win Best Picture (for now; La La Land’s pseudo victory sadly doesn’t count).

As the final film of my initial project, I was absolutely glued to the screen for most of the film. Chicago felt so dangerous, like the unveiling of this side of the city that the silent films and contemporary music of that time most certainly didn’t reveal. I was dead set on granting this film a high rating. Then, the finale happened. All of these brushes with intensity that just seem to dissipate by a conclusion that does seem fitting for old Hollywood: obedient. Of course, this is a problem of Chicago overall and not just Marshall’s iteration, but I’m still reviewing this Chicago film as is. It’s a slight disappointment that left me sour during my first reflection of the film. I was feeling a much lower grade.

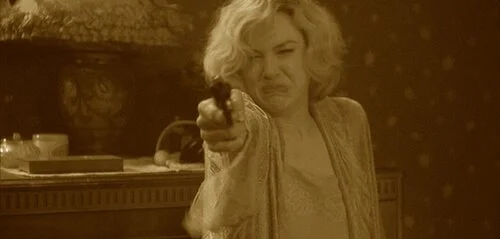

Roxie’s murder is the trial at the centre of Chicago, and all of the new characters in her life are because of this opening event.

Some time has passed, and my bitterness has subsided. Would I have preferred a louder bang as the finale? Absolutely. Chicago flirts with contrasting images and music so often, it only makes sense. While I only watched the film for the first time a few years ago, I had seen a scene or two on television many years prior. I remember being stunned during this one portion, where criminal lawyer Billy (Richard Gere) is essentially merging the wrapping up of a trial with the final number of a production (and the swan song abruptness of both). Imagine an entire film, where jailhouse pestering becomes the best musical single in recent memory (at the time), arguments are now vocal instruments, and legal scheming is percussive.

Although Chicago follows a number of criminals, Roxie Hart (Renée Zellweger) is the main focal point. Her murder of her unfaithful partner sends Hart into a downward spiral. An aspiring entertainer, the hardest time in her life is now a show for all to see, and Marshall (being the production obsessive that he is) makes great use of every single moment. There’s no wonder as to how Chicago was a major component in the revival of the musical genre, because Marshall seized this opportunity by pulling out all of the stops: an electric cast to carry out these powerful tunes, great photography to capture all of the elaborate sets and costumes, and tight editing to glue it all together. Chicago functions as a pulse amidst a troubled mindset, and an era most of us never personally experienced.

Billy with Velma in between court appearances.

Velma (Catherine Zeta-Jones) has already gone through a nearly identical path as Roxie; this feels like the veteran artist ushering in the new prodigy. The deadly duo now become a duet, along with other players in the film. This is why the safe ending bothers me. There is so much right with Chicago. I don’t expect a bloodbath, but some sort of a climax that turns the entire narrative into a gamble (rather than a predictable series of steps) would have made the whole adventure unforgettable. As a musical, Chicago is fantastic. The songs are infectious. The presentation comes from an avid fan, willing to do whatever it takes to bring the genre back. Everyone involved wants to be there. With all of its heart, new life was breathed into the genre. While we have had some standout films since, the musical genre has somewhat been rendered a niche category that you’re either into or aren’t. Chicago was crafted with complete admiration for the glory days of the musical, and with a modern outlook on an old time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.