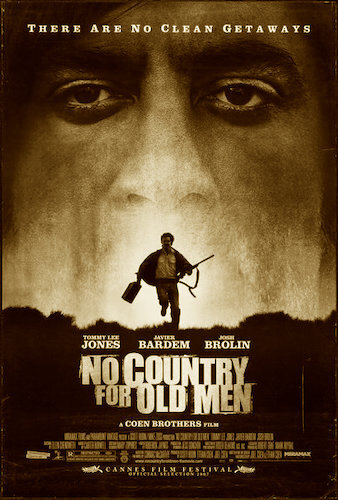

No Country for Old Men

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. No Country for Old Men is the eightieth Best Picture winner at the 2007 Academy Awards.

If there was ever a director that knew the Academy Awards through and through, despite not winning Best Picture… well, let me quickly rephrase this point. If there were two directors of this sort, they were the Coen brothers. Joel and Ethan have seen film after film pick up enough Academy recognition to consider them Oscar darlings, despite none of these films pulling off the big one (or two, considering the directors themselves didn’t win before). Whether it was their writing, or one of their stars making a big splash, Coen films are as festive as Meryl Streep’s name at the Oscars. So, it only made sense that the brothers (and one of their films) would eventually cross the finish line and reign triumphant.

That day came, and it was because of No Country for Old Men. Unlike your common sympathetic wins, Old Men is easily the greatest film the Coens have ever made (and I say this as a gigantic Fargo, Blood Simple, Miller’s Crossing… hell, just as a massive Coen brothers fan). Their adaptation of the novel by Cormac McCarthy created a match made in heaven. McCarthy’s honest-but-simplistic writing style is the kind that can tell stories of the south in such vivid detail, with no fluff to cloud the intentions of the writer (or narrator, depending on the novel). The Coens love bleakness. It’s in their comedy, their drama, and basically the majority of characters they write (how many side parts in Coen films are absent minded people just staring off into the distance, unsure of what is going on in front of them?).

This is a cat-and-mouse chase led by Llewelyn Moss, who has run off with drug money found at a crime scene.

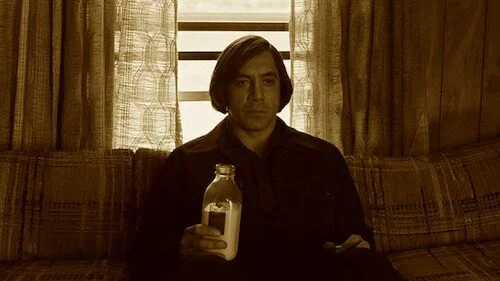

Old Men is still funny (as almost every Coen brothers film is), but it remains their darkest effort by far. Anton Chigurh is the southern gothic angel of death (or, let’s not beat around the bush and admit he is death personified). He is seemingly invincible, and life allows him to linger around regardless of his actions. He never is contained for too long, and always manages to get out of any situation he is in. With all of this success in evasion, Chigurh brings demise to all that he feels warrants it. The others, he leaves with a coin toss: a game of chance to see if you are going to die. We learn about this fate when Chigurh has a conversation with an incredibly simple gas station attendant, who has no idea that he may be killed on the spot. This employee’s ignorance is our fear. We see Chigurh flinch at nothing. We know what he is fully capable of.

With this in mind, we have to now focus on the front-and-back ends of this chase across Texas (and, ultimately, northern Mexico). First off, let’s look at the more obvious character in terms of the film’s plot delivery. Llewelyn Moss is also a bit of a gambler (a fitting role, considering Chigurh’s fascination with probability holding the fate of one’s life). He stumbles upon an abandoned crime scene (in the sense that everyone within this drug deal was killed or fatally wounded). He takes the money and runs. He knows right away that he will be hunted. He quickly finds himself chased by the police, and shortly after by Chigurh. He’s in trouble with the law and the mob. Great.

Sheriff Bell reflecting on his final case, especially after his long career.

The less-obvious character that kind of just follows along is the tired Sheriff Ed Tom Bell. Bell is more metaphorical than literal. The title of the film pertains more-so to him than anyone else. In a direct sense, Bell’s pursuit of Chigurh (and Moss) is him doing his job one last time before he retires for good. Symbolically, he cannot stop evil or death from happening no matter what. Crime will always continue, and his final case has no power over how much evil is left in the world. The amount will always fluctuate, with no help from one single person (although a man of this position is still of high worth in a community, and his deeds are noble). Evil will never ever end. In Bell’s case, death is unpreventable. He finishes the film with two dreams; perhaps his interpretations of the great beyond, and how he made-do while alive. But then he “woke up”, and the film itself ends, as if the dream is finished. However, that isn’t the case. Life continues. Films stop. Bell will die, and the world won’t stop when he does; just his world will.

Of course Old Men is exciting to watch, especially when it comes to Javier Bardem’s spine tingling Chigurh. Seeing his calculated decisions in any capacity is enough to just remind you how unstoppable this guy is. Every time Chigurh tends to his own wounds, creates a distraction, or kills the unsuspecting (or the suspecting; he doesn’t care either way), you worry more and more about Moss and what he’s gotten himself into. By the third act, Old Men transforms entirely. Like Bell’s fear of being unable to stop what exists once he is dead, the film keeps going no matter who is in it. It’s as if we have been awakened from our ignorant slump, but we only have so much capability to understand the dire situation. The film’s runtime quickly drains, as we realize life wasn’t just about one mission, and we’re scrambling to figure out what the rest of McCarthy’s narrative means.

Anton Chigurh waiting patiently to make his next move.

The word most often used for Old Men is “nihilism” (does that mean that these characters “believe in nothing”, Coens?). The only character that seemed to have any sort of good going for him throughout the entire film is Bell, but even his optimism is quickly stripped away. Anyhow, Bell still felt worn down as soon as the film started. Everyone else has a terrible life, or has a great deal of bad coming towards them. Either that, or they are too young to know any better (like the kids that help Chigurh, while you screamed at your screens for them to stop). Like life, there is only a semblance of structure in Old Men. The Moss-Chigurh-Bell chase is all that there is. Once that is finished, there is an empty void, that only McCarthy and both Coens could capture so spectacularly here.

This nihilistic approach is also found in the film’s obsession with minimalism. This means humble sets, few characters, and a lack of obnoxious ambition. Most characters are relatively soft spoken. Deaths in the film end up becoming implied (and all the more frightening) after enough bloodshed has been spilled. Piece by piece, it’s as if Old Men as a film disintegrates before our eyes. Less action. Less plot. Fewer characters. It dissipates in front of us, like a failing mind or a resolving heart fading away. Old Men doesn’t give up as much as it exposes the barrenness of life.

No Country for Old Men is shot with a focus on minimalism, allowing nature to create a bulk of the film’s beauty.

And that’s it. No Country for Old Men is a warning that your own self worth may not be fulfilled, and you can’t rely on life to do anything for your legacy once you have died. Death will happen to all, and no one can change that. We learned that by two auteurs and a novelist legend, a frightening antagonist with the worst bowl cut, and an acting veteran unafraid to show surrender in a film. Characters come and go, and they will in our real lives as well. The Academy Awards usually embraces these roles brought to life, but in 2008, they celebrated the empty husks of a mindless realm we know as reality. This deeply philosophical crisis was brought to you by common people in endless lands, in a genre that usually tells the tall tales of success and escaping death by the skin of your teeth. Instead, No Country for Old Men is a grim western that exists, presents, and concludes by its own terms. The Academy saw something in this cinematic, existential mirror, and we all continue to do so twelve years later. No Country for Old Men is an opus through and through, for the Coens, Cormac McCarthy’s ties to cinema (Blood Meridian is an untouchable novel), and all of the 2000’s. It resembles the indescribable fog of all of our lives better than most of us can even attempt to, as well as reminding us that the clock is ticking while we ponder.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.