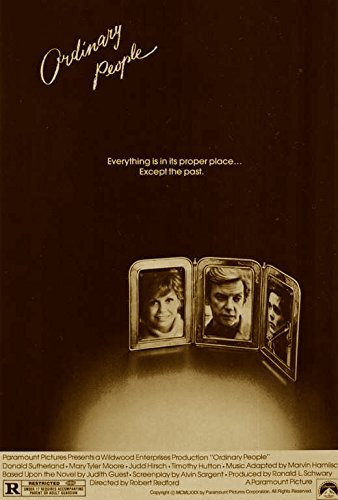

Ordinary People

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Ordinary People is the fifty third Best Picture winner at the 1980 Academy Awards.

Look. I know Ordinary People beat what may be the greatest film of the ‘80s (Raging Bull), likely because of fear surrounding John Hinckley Jr.’s obsession with Jodie Foster (before his assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan, too). That’s a theory, anyway. Yes, Raging Bull is one of the highest achievements in cinematic history, and it’s a shame it didn’t win Best Picture. However, I am also sick to death of Ordinary People getting the short end of the stick when it comes to this discussion. Should it have won? No. Is it a great film that managed to win Best Picture? Absolutely. It’s not as though some terrible film won instead. Ordinary People managed to capture the essence of ‘80s cinema right at the very start of it, through its softer edged takes on very real problems (without sugar coating too much either).

First-time director Robert Redford clearly knew how to work with actors (being a strong performer himself), and he used his knowledge to drive Ordinary People into becoming a very strong analysis of a mangled family, still suffering from the death of one son, and a suicide attempt of the other. Another newcomer (in the form of Timothy Hutton) steals every single moment he is on screen, as the conflicted Conrad Jarrett; a guilt-stricken brother that survived his own efforts to kill himself, and is trying to mend both himself and his parents. He hates being tangled up in anything. He just wants it all to end. It’s a lot of responsibility coming out of such a young actor; it’s no wonder he ended up being the youngest male performer to ever win an Academy Award for acting. For this then-young star to step into the unknown, with an actor-turned-filmmaker, is a huge undertaking. To watch both succeed is fascinating.

Conrad’s relationship with his psychiatrist is a major focal point for Ordinary People, as Conrad is usually uncomfortable opening up to anyone else.

When it comes to some of the other veterans, Ordinary People loves to place talented people in roles against type. Judd Hirsch went from everyone’s favourite television comic to having a fantastic dramatic turn as Dr. Tyrone Berger (Conrad’s psychiatrist). Not only is his role anatomically correct (he has been championed for having a more authentic approach to being a cinematic shrink), but he also has the goods to deliver a flat out strong performance (especially as the main nurturer of the film). We also have Mary Tyler Moore turning from everyone’s favourite television leading lady, to being a tortured mother, stricken with grief, who holds a resentment against her son because she doesn’t know how better to deal with the death of her other child. I wish we saw more work like this by Moore, who clearly knew how to command scenes as a difficult character (and not just a charming one).

Donald Sutherland plays somewhat of an anchor: a more quiet parental figure, who has to take a step back to try and cope with his family falling apart. He may be more passive, but his presence is still abundantly clear (especially when he cannot hold on to so much anguish anymore). Putting all of these characters into one film guarantees conflict, and Ordinary People has it in spades. While there is a forward-moving plot (Conrad trying to heal, the Jarrett parents trying to find peace again, amongst other threads), a lot of Ordinary People is based on vignettes that happen to correlate to one another chronologically (holidays, major events). You can observe how the family is doing through these moments, and the result is usually not so great; in fact, you usually find a whole new slew of problems within the Jarrett household with each new attempt to fix these woes.

The struggle between the Jarrett parents to repair their happiness becomes a major problem in Ordinary People.

Once you reach the final scene, you will most likely feel absolutely empty. Ordinary People is based heavily on the readjustments necessary to continue living through trauma, and so it has a conclusion that is tossed up in the air. I dare anyone to feel snug during this film (especially once it finishes). It’s simply impossible. As a moving take on familial survival through mutual devastation, Ordinary People is a stellar example of how such an approach can be done. It’s incredibly basic conceptually, but it goes through extreme lengths emotionally. Don’t dismiss this film simply because of the asterisk near its Best Picture win that so many journalists use as a means of hiding the film’s existence. I insist that you give the film a try, because laughing it off because of its controversial Academy Award win is to be foolishly ignoring a gripping drama that started the ‘80s off with a bang (and a bunch of tears).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.