Memento: On-This-Day Thursday Review

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

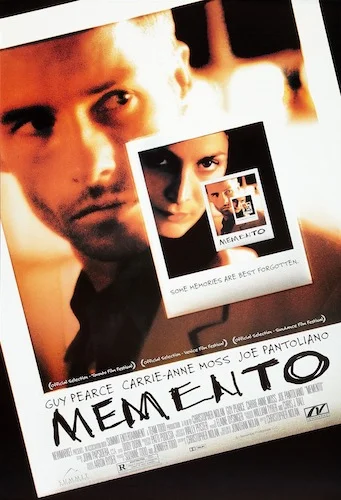

For March 14th, we are going to have a look at Memento.

How much is a memory worth? The value of your thoughts can change depending on where you place the weight in these recollections. If you won the track meet back in fifth grade the day your first crush embarrassed you, how does it play back? Is it a day ruined, or perseverance reigning triumphant? In a noir film, one of the biggest regrets any lead has is the ability to long. It consumes them. Shrouds their world. Suffocates their minds. In the neo noir Memento, a curse becomes a blessing: a chance to do it all again. It is in full colour when played "live", yet all of the fragments of Leonard's past are grey; one storyline is an escape from the depths of noir hell, and one is halfway there.

Christopher Nolan broke through with Memento, and he has not quite achieved the same level of brilliance since (while he has occasionally come very close). There aren't any gimmicky reasons to have two films running at once (not in the insulting sense, anyways); this is an understanding that time does not play its usual role here. Tattoos dictate exposition. Polaroid images are narration. Leonard remembering it all is the plot. The idea of an unreliable narrator is so uniquely bastardized here, because the narrator is no longer aware that he is even telling his version of a story, let alone acknowledge that he has an audience.

Leonard Shelby has short term memory loss due to an unfortunate attack; the same break-in resulted in his wife's death. He vows for vengeance. He makes his mark. He finds a way to kill these criminals for what they have done, despite not remembering anything since the attack happened. All he has left are the screams of his wife, indicating her final breaths were ones of agony.

Leonard Shelby in Memento, played by Guy Pearce.

It is a challenge to discuss Memento without spoiling any of its many twists and turns. What I do know is that its unconventional delivery of story only ages better as the years go on. On a first watch, Memento is a game you try to play at home. You have to do a mental play-by-play. The second viewing is trying to see where you slipped, because you did not piece the story together quite right. The third watch is an appreciation of it all: the dive into the mind of a criminal, and the panic of the innocent grasping for the last shreds of life. The best part is, this point means something completely different depending on if you have seen the film or if you have not.

Nolan tapped into his signature style here: ambitious blockbusters. There is enough philosophy and psychology here to wrack your mind, but enough thrills to entertain the easily bored. Nolan now is a divisive filmmaker; one who does not fit squarely within the most mainstream works, or the distinguished art house pictures. He is seen as either a snob or misunderstood. Like half of Memento, I see Nolan in the grey area: overly appreciated when he is called the greatest of all time, and under estimated when he is left out of the conversation altogether.

An example of a flashback.

Memento is evidence of his importance. The likeliness of attracting both the entitled elite and the distracted masses is very slim, yet Nolan pulls off the impossible time and time again. Practical effects are favoured. A complicated execution of a basic story spices things up, yet renders his tales understandable. The epic scopes of his mind games at least make all of his works linger with you. With Memento, there was no major budget, star studded panel or expectations. There was only drive: drive to make a new type of thrill in the way Hitchcock or Towne did.

The idea of a human heart getting in the way of sensibility is done so differently here. There isn't any sappy syrup or tired morality. There's only human error. Nolan's coldness has been interpreted as inhuman, but it works so well with Memento, because every scene is a battle to remember. Leonard feels he has lost all that is human about him; this time, it makes sense.

Leonard and Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss) together.

Memento started off as a challenge nearly twenty years ago. It now sits as an expectation. Not many films have even attempted its plot delivery. Memento wasn't even the first film to be unorthodox with its sequencing. It's just idiosyncratic: of its own kind. It has been mocked and parodied, but otherwise it has been left alone. Maybe Nolan himself could never pull off this exact narrative stunt ever again. Memento is a rare instance of a film having worked once and exactly once, mainly because no one wants to see what happens to a beautiful risk when it completely fails.

The film ends in such a way that its entirety turns into an unstoppable nightmare. Memories are images and sounds we cling on to, but that can also get in the way of our current reality. In Memento, it does so in such a way that reality is a complete and utter mess. There was something about the early naughts that had filmmakers interpret how we long for our past. Charlie Kaufman saw our pants as tangible in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Sofia Coppola turned memories into a state of chaotic limbo where the present is a harsh reminder in Lost in Translation. Nolan turned the shards of one's past into the daggers that pierces their current state. Maybe the turn of the new millennium had everyone looking back. Maybe the future had us all concerned enough to not look ahead. Maybe cinema got to the point where home videos merged with fictional tales enough to know that cameras were the receiving end of moments. Either way, Memento is an untouchable product of its time, which is strange because it despises the very idea of time being reliable.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.