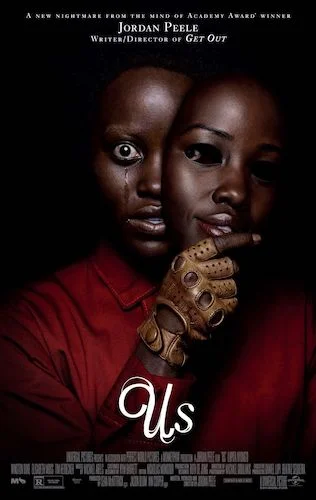

Us

Us is a very deceiving title. It is evidence that sometimes less is more. You go in wondering how an ambitious second feature by Jordan Peele could rest simply on one word. You find out it is actually two letters. The U.S. is us. Once again, Peele has created an alternate dimension that says more about society than realistic dramas do. With Get Out, Peele put together a connect-the-dots psychological thriller that placed American racial politics at the very core. With Us, we have a majestic web of a billion ideas. It may sound like a copout to say, but the current situation of the world isn’t easy to define. Peele doesn’t try to solve it. This time, he flat out just showcases it exists through a new perspective. Us can be frustrating for thriller purists that demand answers with every turn. This is the kind of film that allows you to figure it all out on your own, between the nightmarish images, and the quilt of symbols. Peele was the perfect candidate to host the new Twilight Zone series, especially seeing how Us is a never-ending Twilight Zone episode (it’s as if the big reveal at the end of the episode keeps going, because this is a marathon).

Get Out’s story is much tighter; every single question had an answer. Us is more elaborate with its ideas, but less inclined to detail everything. As a result, Get Out makes more sense, but Us expands the darkest depths of your mind a thousand times more. You can’t squarely pinpoint it down as racial politics this time around. This is hell, but it’s America. In probably the most defining moment that stopped my heart (more than any jump, any shed of blood, any scary image) was the phrase “We’re Americans” as an answer to the film’s defining question (why is this happening?). For me, that was stomach churning.

Adelaide and her two children.

Two key elements are why this film not only works, it’s downright unforgettable. As previously discussed, Peele’s directorial lens is a major factor here. It’s more than just the fact that a director and producer is working on his own screenplay. Peele has a great eye for juxtaposition, and he’s gotten even better with it this time around. We start off with an old television set blasting retro commercials at us, with a young Adelaide’s eyes reflecting. A commercial for Hands Across America plays. This innocent plug features many images of smiles and faces in different moments. Back in 1986, this was a uniting of citizens. The way Peele plays this out, it’s the damnation of a civilization. All of these blank faces and broad smiles, locked in grids. This is later contrasted with the opening credits sequence: a zooming out of a wall of rabbits locked in cages as if they were bodies in a morgue. We may smile, but we are stuck in these cells for life.

Aside from Peele’s spectacular use of references, combatting symbols and metaphors (which I will refrain from digging up to avoid spoilers), we have the criminally under-utilized Lupita Nyong’o finally being given a complicated leading part. As a regular mother, Nyong’o makes an adult Adelaide still highly relatable. Then, her fears kick in. They are so subtle but so effective. There isn’t any mugging for the camera here. There is only authentic chills. Adelaide only remembers her trauma but not the core root of her worries, and it only makes things creepier for us.

To truly get into this film’s power, we need to dissect it properly. Please avoid reading anything in this section if you wish to not have any moments spoiled.

SPOILERS

The other side of Nyong’o’s performance comes in the form of Red: Adelaide’s dopplegänger. Her voice croaks in such a way that will either terrify you, or just come off as strange. Either way, you cannot mistaken it, and you cannot shake it off. It is so alien to hear. Red doesn’t come off as a run-of-the-mill horror creep either (with the overdone head tweaking, the glossed over eyes). There’s something slightly different with Red, which makes sense once you reach the ending. How Nyong’o pulled off this feat is beyond me.

Adelaide being confronted by Red.

The clones are revealed very early on. If you include the opening sequence, the notion of the “other” is basically found in the very first moments. The actual onslaught of America’s doubles happens within the start of the second act (when most horror films would leave this kind of slaughter for the climax). We think about how far we are into the film. We haven’t even come close to an hour. We’re maybe half an hour in. We know we are going to be in this nightmare for a good while. It’s scary, but it’s actually exciting. We see the family kill their own doubles in different ways. Gabriel’s double dies by being killed by the new possession the real Gabe loves: his prized boat. Zora is keen on driving, but the double dies due to her (intentionally) careless maneuvering. Jason is obsessed with his own little tricks, but gets his double to succumb to one of his own. Adelaide kills red through a bloody dance during the film’s climax. Vehicles. Opportunities. Fun. Art. These are the privileges the tethered only wanted, and the bare exposure to them is their downfall.

The real world is clearly the upper class. The Wilson family clearly have it at least kind of good, if they are able to afford a summer home and a new boat. Their friends — the Tyler family — have it even better with their multimillion dollar smart cottage. They are the upper class, because they literally live in the upper world. The “tethered” (the clones that live in the underground subways) live below, and are the lower class. They don’t get their amusement rides, carnival snacks or other luxuries. Their actual natures being ambiguous makes everything even creepier. Are they literally tethered to the actions of the above-ground citizens, or are they only mirroring us voluntarily? Either answer is upsetting to think about.

But, let’s talk about that ending. That golden escalator that only moves downwards. The rabbits running amok. The empty hallway. The escalator is clean; without even fingerprints, never mind dust or dirt. It’s never used. It can be used to go up. Sure, it would be difficult to run in the opposite direction, but it’s doable (“Adelaide” did it, right?). It’s there, glowing for the tethered to take advantage of to visit the real world. It never was used, because they were told they couldn’t use it. They only used it to reach the surface world now. The opportunity was always there, but a higher power made it feel impossible. The rabbits, despite being the food for the tethered (probably because they can breed easily for more meals in a literal context, or there’s the million metaphorical reasons, too), are now free. The rabbits are the tethered. Tethered humans left, and the rabbits broke loose. Humans remained, and the tethered had to kill them once and for all.

Jason seeing a stranger on the beach.

Finally, there is that twist. Just like the one in Get Out, it’s actually difficult to not predict this twist from a mile away. Of course Adelaide was the clone from thirty years ago, having resurfaced as the real “daughter”. The signs are all there. Red is the only clone that can talk (the real Adelaide clearly having lost her ability to communicate well because she was strangled as a child and never properly healed, and she hasn’t had to talk the same way in the underground ever since). Adelaide also remained quiet after the traumatic incident. Adelaide also has random flashbacks that aren’t represented by images, but feelings (a strange euphoria when remembering that awful night). It’s actually painfully obvious. However, Peele never likes to rely on these twists, but rather use them as universe enhancers. We know we’re in a satirical look at our world. We can gather all of the oddities and inspect them. These twists are just a cherry on top, and not the reason why you watch these films. As a result, Us does not suffer even a single iota. Having Adelaide suddenly remember that she was the actual clone isn’t a problem; it only enhances the entire theme of privilege and uncontrollable worth even more (she was the only tethered person to have riches).

END OF SPOILERS

Us is so full of ideas and images (like Get Out), that a second viewing is not just earned; it’s downright essential. You know so many little tropes are intended. Adelaide sees a carnie with an authentic Black Flag shirt; in the present day, some beach-goer has a clearly marketed Black Flag t-shirt that wasn’t from one of their actual concerts (but a store, most likely). What is the exact purpose of this? It’s debatable (I personally see it as a shifting tide in value, and the never-ending thrill of consumerism that the fortunate get); for all we know, Peele or the costume designer could really just like hardcore punk music. The choice just seems so intentional, though.

Us is another stellar entry in Peele’s brief-yet-phenomenal library. It is a little less air tight than Get Out, but it is much more imaginable. Even though both works are horror-thrillers, this variation into a more artistic fear-fest is nice, because we now know for sure that Peele wishes to explore the unknown (with the blatantly known) in a capacity of ways. These are two horror films buoyed by politics, but they are extremely different from one another. It’s also nice to just be a part of a mindset without a megaphone blaring “answers” in your ear. We can experience a variety of problems (particularly classist struggles) with this super dark lens. Us is about the beings that resemble us, but it’s literally about us (the viewers, for the most part), too. The super long Twilight Zone episode ends, and you walk out of the theatre. This is the real Twilight Zone twist: everything is now foreign to you, as if you yourself have entered a new reality (or even just the above world).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.