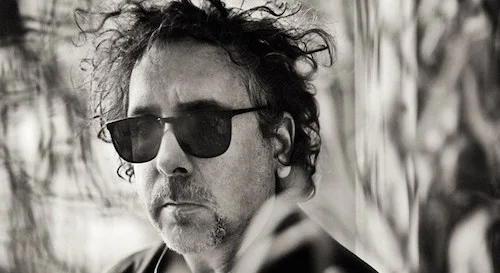

Tim Burton: Analyzing Our Childhood's First Auteur

We have discussed Tim Burton on this site before, between the Alice in Wonderland retrospective review, and the look at the Disney live action remakes (this referenced Dumbo, of course). In a more quiet news week (outside of Apple TV+), it might be a good idea to really take note on why this particular director starts off as the most identifiable auteur for new cinephiles, and why he slowly vanishes for a number of movie goers.

When you first discover films as a child, many works can blend together. If you don't know what a “Roger Deakins” is, or what “Thelma Schoonmaker” does, you may just notice many works flowing similarly at a young age. Chances are you're not watching crazy arthouse films, so there won't be much experimentation there. For many of us that were young when his films came out, Tim Burton was capable of having such a unique style in the mainstream. The muted pastel colours (or greys). The exaggerated scenery. The Hot Topic gothic vegetation. There is something starkly different between these sets, and something you'd find in many other films at that age. They're different, because they are all clearly from the mind of the filmmaker.

Burton has always dabbled with general audiences, too (at least in every era). ‘80s children had Pee-wee's Big Adventure, Beetlejuice, and the very first Batman film. ‘90s kids enjoyed The Nightmare Before Christmas, and Mars Attacks!. In the ‘00s, Corpse Bride and the Chocolate Factory remake were around. There was also more mature works for teenagers or adults (but mostly teenagers). Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood, Big Fish and Sweeney Todd (all arguably his best films) were around to blend childhood imaginations with adult dilemmas (identity, dream chasing, legacy, and guilt).

A scene from Burton’s opus Ed Wood.

In the '10s, we now have two Disney live action remakes (plus a spin off of Alice, which is still Burton inspired). Big Eyes is the mature work that shows a more inspired Burton trying at least something a little different. The underrated Frankenweenie feature length film (that would round out his top five) was the authentic flick for youths that showed some forms of promise. However, Dark Shadows happened. So did Miss Peregrine.

At some point, through hits and misses, the singular style gets a bit tired. Unless you are a Burton superfan, you might crave something a bit fresh. Martin Scorsese has top toed through many works (gangster flicks, period piece dramas, raunchy comedies, even a family film with Hugo). Quentin Tarantino obviously had a voice, but he hops around genres and cinematic tributes like there is no tomorrow (Hong Kong cinema, French New Wave, blaxploitation films, the works). These are also mainstream filmmakers. You look at other auteurs, famous or not, and there is still some breathing room.

Then we get to the more eccentric filmmakers, where Burton lies. David Lynch. David Cronenberg. Gaspar Noé. Place any edgy or unnerving filmmaker here. While they still have their own very specific styles, you tend to get something a bit different from each film. Lynch loves the surreal, but he tries to activate different psychological and subconscious ghosts. Cronenberg loves body horror, but each disease is different. Noé pushes buttons, but he has a new shtick each time. These are all still the same goals, but the formulas feel a bit different at least.

A memorable moment from Big Fish.

The reason why Burton keeps certain fans, and loses others the more they discover cinema, is because he loves to contain the exact same feeling of the misfit being left out of the world. Edward Scissorhands was integrated into an American suburb, and then cast out as a monster by these same people. Ed Wood was never understood as a filmmaker, because he never had the financial means or talent to pull off his aspirations. Edward Bloom created his own fables to make his mundane life seem richer to his children. There are many instances of characters not named Edward in any way, of course. Having said that, every single film of Burton's targets an outcast, or pays tribute to an outcast's favourite slice of pop culture (Dark Shadows, Planet of the Apes, Mars Attacks!, even Batman back in the day is debatably for the outcasts of the late ‘80s).

Why did a number of his films work better then? Did he just get stale? That's where you begin to learn what an auteur really is. Behind every director is a whole team of individual crew members that use their own expertise to cater to a singular, signature style. His casts are identifiable alone. How many films has Burton shot with Johnny Depp, Winona Ryder, Danny DeVito, and, of course, former spouse Helena Bonham Carter? How many films has Danny Elfman scored? Burton has worked with similar crew members, like cinematographer Stefan Czapsky, editor Chris Lebenzon, costume designer Colleen Atwood, and many more. You pinpoint which crew member worked on which film, to see which roles they carry (from the light to the super-important). Atwood has worked on so many Burton films as it is; you begin to understand her work as her own once you learn more.

Burton is a lover of his own ideas. He has a whole squad to bring them to life. Sometimes, the director has to do some of the actual heavy lifting. With Burton, a niche has been established, and it does him and his friends well. His biggest fans cannot complain. It almost feels wrong to complain, myself. Like many of you, Burton was the first director I ever knew about as a child. His name plastered on one of his unique-looking films was as magnetic as the gothic imagery used. "Tim Burton" told its own story when featured underneath a blade-clad automaton, a sea of alien brains, or a gangling skeleton lamenting the full moon.

A climactic scene from Edward Scissorhands.

For the big school of film that exists only hypothetically, Tim Burton is the first grade teacher you had. Things started to kind of come together. You knew sets had to be made, costumes had to be sewn, and faces had to be done up. It was a semblance of film in a way your young eyes had never seen before; at the same time, it was a disassembly of all of film's components as you were finally being made aware of all of these parts. You graduate and go to second grade, where Mr. Spielberg is teaching, then Tarantino, then Truffaut, then Varda, then Eisenstein and so forth. But Burton was the first face you knew. You check in to see how he's faring. Sometimes he's doing okay. Sometimes he isn't. If you're a part of my generation, it is perhaps easy to move on from Burton, yet hard to dismiss him entirely.

He may be the doorway into your love of film from the start. Edward Scissorhands was an emotional catharsis for a young, teenaged me. As I studied film, the spell started to dissipate. Pacing issues rose up. Plot holes showed themselves. Weird edits began to confuse. The magic was gone. The next decade plus, I find myself at least being grateful for the time we had, that film and I. His films are like him: misfits that fit in some places, but not all. My cinephile mind has cast these flawed works away, but the film loving heart will put these films on once in a while just to reconnect. Edward Scissorhands means well, considering.

Dumbo will be reviewed later this week, and I'm not sure how that will go. Whether a great reunion takes place (Frankenweenie), or a bitter fight occurs (Alice in Wonderland), it will just be nice to check in on the old teacher; the first auteur for many (after Steven Spielberg and George Lucas dazzled ‘70s and ‘80s kids), who may very well inspire many children to look deeper into the creation of these universes. The Burton fascination for me has been long gone; the gratitude for his work turning a childhood me into a movie lover remains.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.