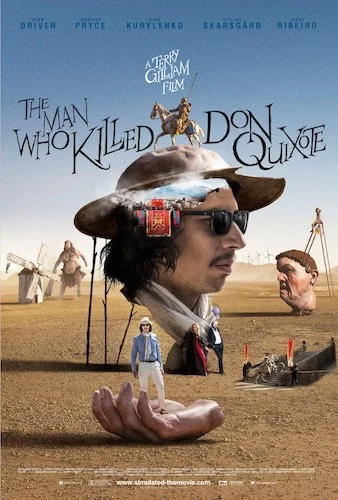

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

Thirty years. Nearly thirty years. That’s how long it took for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote to come to fruition. Studio cancellations. Legal troubles. A revolving door of performers. Even the last couple of years, when the production actually did commence, were a nightmare. Terry Gilliam had to deal with a lawsuit from a former producer over the release of this film. The film experienced a lukewarm Cannes reception. Gilliam nearly died from what was reportedly a stroke; it may not be a coincidence that this occurred after Amazon Studios backed out of a distribution deal. The film has had a whimpered tour across the globe, opening in a few theatres here and there. It’s finally available in American theatres. It can finally be seen. There’s a slight chance you were meant to be in the film and you weren’t, and yet here you are ready to watch it now. All of this, for a critical shrug.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote possesses the ambition of Synecdoche, New York, but its grossly exaggerated quirks hold it back from being as profound as it can be. It is a strange satire like The Player, but it tosses in enough bizarre elements to not resonate on an identifiable level. Despite a number of its flaws (unnecessary, crude moments being the main enemy here), it is difficult to shun this project. I can see why Gilliam was so hellbent on making this film. We have a director, whose student film permanently changed an old, fragile shoemaker’s life (once he started to believe he was actually Don Quixote for the last ten years). We have the return of said director to this tampered village. We have the eventual turn-around. This is the impact of cinema one can have. This is the over-done work of a method actor (especially if it’s a random villager with no previous experience). This is an artist falling in love with their craft all over again, albeit through delusion.

Filmmaker Toby Grisoni being trapped due to his own previous mistakes.

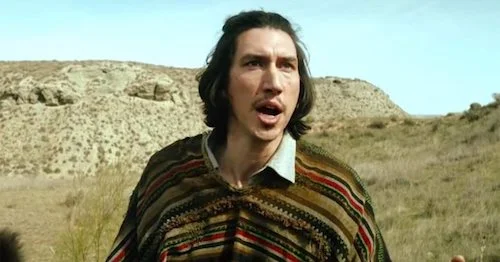

The giant hands and heads on director Toby Grisoni’s set are very La Dolce Vita or Ulysses’ GazeL a metaphysical embodiment that is a literal work of art turned into a godly, dominant metaphor. The yellow-green colour scheme of the cinematography is also a nice touch. You know off the bat that there was something here. You can do away with the urination jokes, or the Christian crusader Quixote staring at a woman’s chest. These arbitrary moments in an otherwise determined film can be completely disregarded if you try hard enough (it’s just a shame that these are moments that somehow made their way in a sought after film). One other key feature makes Don Quixote worth a shot: Adam Driver’s sensational performance. I don’t know which filmmaker he channeled to get this egotistical, panicked take, but someone clearly did Driver wrong (but right for this project).

Seeing the fictional world and reality blend is fascinating. You go in expecting Don Quixote (or Javier, who believes he is Don Quixote) to just mumble and run around going crazy for the world to see. Instead, we see a merge of an artistic vision, and an everyday life. Gilliam also has a political statement (as he always does) here: this time, it’s a take on how religion may be no better than the cinematic stories we worship. If Javier treated Grisoni as a God (one that gave him a chance to have a rebirth), how is that no different than the kinds of beliefs Gilliam usually attacks? This statement is slight, not quite fully realized, but it’s an attempt.

Javier never snapped out of character, and he fully believes he is the literary legend Don Quixote.

It’s strange that more difficult films that take on meta themes have perhaps pulled them off better. Holy Motors is a highly abstract take on cinema, but its portals into different visual molds resonates the entire time. Inland Empire may not make pure cohesive sense, but you know where you stand on its take on character parts in Hollywood (how is acting in a film any different than acting like a different person to win parts or jobs?). Don Quixote could have been at this echelon of meta films about cinema. It clearly derives a lot of philosophical elements from French New Wave or Italian Neorealism. Gilliam’s incessant need to toss in the grotesque makes it a Gilliam film, but it also slows down its grandiose escalation.

It may miss the highest mark, but that does not make it a lame attempt. Don Quixote clearly is a story that had promise, and continues to show it (at least in a variety of ways). There is something poignant about cinema here (and its importance on a cast, crew, and audience), especially in regards to how commercialism kills a drive. This metaphor only got hungrier with the production hell history the film experienced. All of that doesn’t get lost. Everything is abundantly clear. Synecdoche, New York lingers with you for a lifetime. Holy Motors causes you to reach for emotions you didn’t know existed. Inland Empire is a stirring nightmare. The Man Who Killed Don Quixote could have easily joined this batch of films, and you can even see this when you give it a try. It doesn’t quite do that, but there is enough passion and love here that the film will still stick with you at least for a few days. Gilliam may have crafted better worlds and more succinct ideas (even the satirical kind), but at least Don Quixote was finally allowed to live. He deserved that much.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.