Twin Peaks Week: The Pilot

The Pilot

Twenty nine years ago today, a peculiar program started that changed television forever. It forced supernatural shows to get weirder, police procedurals to get more gruesome, love triangles to get campier, and every other show to get more cinematic. There was never a show that felt like a never-ending film at the time. This is, of course, Twin Peaks, created by surreal filmmaker David Lynch and television screenwriter Mark Frost (who was best known for his work on Hill Street Blues at the time). Twin Peaks is a complete bastardization, that was a meta commentary on nuclear families fixated on television series week in, week out. An entire week to truly analyze its impact is necessary (a week for The Return alone would be great, but that just cannot happen right now). Today, we have to start right at the beginning. The pilot was not only the best indicator of what this show would be like. It was also, arguably, the greatest television pilot of all time. The only show that comes close, Lost, is a show that was famously influenced by Twin Peaks altogether (just as an extra affirmation on that front).

So what is Twin Peaks? The fictional town’s name is basic: it resembles the place at the bottom of a pair of mountains in the northern Untied States. Simple. In fact, that’s probably the only simple thing about this show. Yet, like any great story, the title carries more than one purpose. Duality is a highly common theme of this show. We have the double lives of the citizens here, all of whom were stunned when their town got flipped upside down, only for everyone (and I mean everyone) to have a dirty secret. This is a reference to literal doubles, as well. With the existence of parallel dimensions, access to the subconscious, and other metaphysical portals, we gain access to literal copies of people, events, and more. The mountains eclipse one another, yet are two different natural structures. Twin Peaks operates the same way: it isn’t about the two separate lives people have, or the spectrums people live either side on. It’s about the middle ground: the discomfort a merging of two different realities (literal or metaphorical) can have.

The entire show is anchored around the life and death of Laura Palmer.

Where does it all begin? With the discovery of a dead corpse all wrapped in plastic, of course. Life was going on as usual, as lumberjack Pete Martell goes fishing first thing in the morning. We don’t see much of how Twin Peaks operated outside of this brief opening, which is a great opportunity to let each and every dark secret being revealed become their own focal points. Instead of caring about characters we got to know for a while before all hell broke loose, we just see a foundation we barely just got to know slowly break. It’s a beautiful disaster. The entire series is a bittersweet blend that replicates the morbid opening scene of a dead homecoming queen. All of Twin Peaks is a fixation on a gorgeous nightmare, a delicate tragedy, the worst outcome of someone that appeared to be a stunning soul.

That corpse that Martell stumbles upon is Laura Palmer. She is wrapped in plastic, like a chrysalis containing someone evolving into a transcendent, tortured spirit. This appeared to be the first true blemish of Twin Peaks as a town, but it’s only because it was the first personal thread that publicly ended with a disaster. With the wrench tossed into the mill that operates at the heart and soul of the town, every other nefarious scheme begins to fall apart. With collapse comes revelation: a building cannot fall down without a booming sound and a cloud of smoke that alerts everyone.

Special Agent Dale Cooper’s first scene, shown almost halfway through the pilot.

An outsider can be the kind of person that is able to spot discrepancies much easier than inhabitants can. Enter Special Agent Dale Cooper: an FBI agent sent to Washington to look into this uncharacteristic murder. We don’t even see this leading character until roughly half way into the hour-and-a-half pilot. Instead, much of the opening act is devoted to seeing the foundation of a loving town begin to crumble. We understand why Cooper falls in love with this humble town, because we were also given that chance (despite the bad news that has entered every household this day). Like us, Cooper is seeing all of this from a vantage point; not as an expert in his field (which he clearly is), but as a person not lodged in the machine. By the time Cooper gets to Twin Peaks, we are seeing just how tightly knit the town supposedly is. Once he gets there, we begin to see what a miasma it actually is. No parallel dimensions. No dream worlds. This is literally all within the confinements of reality, and every civilian is unaware of how deep the rabbit hole actually goes (even some of the main perpetrators don’t know quite the scale of this underworld).

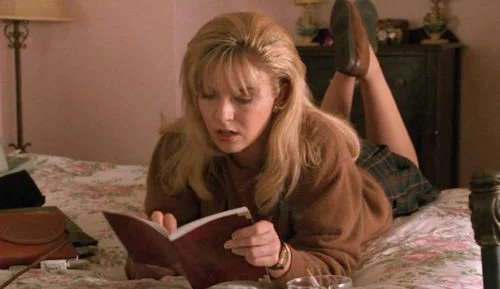

The moment Donna Hayward realizes her best friend is dead.

Everything comes to a screeching halt, even literally: the Packard mill is told to cease operations as a gesture to Laura Palmer’s death. Otherwise, we have the police force face a crime they aren’t too familiar with, the local diners and businesses turn frozen, and the high school get dismissed early. When it comes to the neighbourhood houses, it’s as if death knocked on each and every door. This isn’t some random girl that lives in the area (and it was too close for comfort). This was Laura Palmer: our daughter, best friend, homecoming queen, meals-on-wheels delivery person, lover, employee, tutor, and more. The amount of responsibilities Palmer had wasn’t indicative of a regular life, but a symbolic take on the magnitude a murder can have in countless ways. Palmer herself led a double life: the face of the town by day, and everyone’s exploited muse by night. As the series progresses, we find out more and more how Palmer was violated, abused, and coaxed into darkness. She was everyone’s championed angel, which made her responsible for the demons of everyone else.

Laura’s mom in the pilot episode.

We are seeing everything unfolding on a literal level in this pilot episode. Something still feels a little surreal, though. It could be the cinematic angles, the dreamy-yet-punishing score by Angelo Badalamenti, or the slightly-off behaviours of the townspeople (let’s never forget that random dancing high school student in the background of that one scene. I don’t even need to explain more. You never forget it.). We get a few senses of paranoia to keep us on our feet. Sarah Palmer (Laura’s mom) feels that someone else is with them while police are investigating her household; it’s just someone else upstairs. Still, even if you know nothing about David Lynch’s previous films (or entire filmography, if you entered the Twin Peaks fandom later), something is a bit foreign here. That’s when we see a ghastly figure right at the worst moment: a glare of death looking up at us, from a stranger we’ve never met. We come to learn that this entity is “Bob”: a presence that possesses bodies and drives people to the darkest points of evil. Think about it for one second, though. We don’t see anything of this magnitude until the end of the pilot episode.

That is one reason why this pilot is iconic. We begin to understand what the rug being pulled from under us is like. We know Bob isn’t real, because no one else sees him at that second. We have no clue who or what this guy is. If this doesn’t ring a bell, this is how the international version of the pilot ended. The original version still ends with an unsettling image: a hand digging into the ground and picking up a half-heart necklace. This is a vision by Sarah Palmer, which further indicates the element of the unknown at play here. No matter how the episode ends for you, you have something that stays with you. It isn’t necessarily a cliff hanger or a twist. It’s an ambiguity. This isn’t The Twilight Zone, where that’s the end. This is episode one. You know there is more to come. This is the start of hell opening up in Twin Peaks. What anticipation!

Bob being featured in the international version of the pilot.

Chances are you didn’t see the international version during your first view through of the show. This version was made as a safety measure to at least wrap up the pilot as a way-too-open-ended film (but still a stunning experience) if the show was not picked up. We’ve seen something similar happen in a masterful way: Mulholland Drive (another show Lynch wanted to get off the ground, that got turned into a film after the pilot failed to secure a deal). For me, Mulholland Drive is the opus of Lynch’s career (and indisputably the greatest film of the 21st century). Why did Twin Peaks make more sense to turn into a weekly adventure? Maybe seeing the parallels of a town experiencing a fragmenting of many shorts just made more sense than the meta deconstruction of a film and its parts. In fact, seeing the deaths of nuclear families and soap opera flings makes more sense for the small screen than the murdering of Hollywood does.

That’s exactly what the pilot of Twin Peaks showed us: the death of nuclear television. The synth score by Badalamenti is unforgettable: the deep chords courses through your brain, and the higher melodies lift you out of the deepest depths of hell, like you are teetering between life and death. There’s no cheerful, upbeat melody that ushers you in-and-out of TV land here. There is a damning theme that never lets go. The official title theme (an instrumental version of a Julee Cruise song, also created by Badalamenti) is uplifting in a very serene way. This is no jingle. This is an experience.

A spectacular shot near the start of the pilot.

The dynamic single-camera shots are replaced with images that came off the silver screen. One shot that comes to mind is a steeply-high shot of the stairway in the Palmer household, with the ominous ceiling fan spinning at the top. Sarah Palmer darts her way up the stairs to find her daughter. Something is a bit off here. These aren’t the same stairs she’s taken for the last countless amount of years. This is the last time she will climb on top; her descent down will be a permanent entry into the underworld she will be trapped in for the rest of her life. Electricity also plays a dark role in Twin Peaks, as if telephone lines are passageways for evil to travel, and outlets are gateways for the unknown universe. The shot cuts to a close up of the ceiling fan, whose whirring sound turns into a thudding ambience. There is an uncertainty in the normal. This entire household is not the same. Nothing has changed, but we still have a duality here. Twin Peaks’ theme of the double lingers in every single way.

We can go into the minutiae: the moment the school realizes Laura has died, the characters all reacting to the horrible news, Cooper bringing a sense of professional optimism to a town that operates its own way, all of it. However, all of that pop culture has lingered throughout the show (and will definitely be reflected upon throughout this week). For now, we will conclude the pilot’s legacy in this article by celebrating how it confronted television with two options: change, or death. Like the mirrored citizens, events, and locations in the show, television was now forced to become a pale comparison of itself, or to venture forth into the new realm of household entertainment. The Sopranos garnered the confidence to become a weekly super-long film. Lost did not hold back on the shattering of conventionality. The X-Files enjoyed dipping into the unknown on a larger scale. Do we even need to go into Riverdale, Wayward Pines, and all of the other come-and-go shows that share a much stronger resemblance to Twin Peaks? There is nothing wrong with the impact this show has made being interpolated; it’s evidence of the show’s staying power. The tale of the death of innocence (in the form of a teenager’s demise, and the downfall of a small town) strayed way from the reliability of conventional television. The story gets resolved at the end of the episode. Everyone that is good makes it to the finish line. Everything gets wrapped up, at least thematically. Twin Peaks offered none of that in its brilliant pilot, and we absolutely had to have more.

Join us for the continuation of Twin Peaks Week, where we will go through the entire series, Fire Walk With Me, The Return, and even the canon books.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.