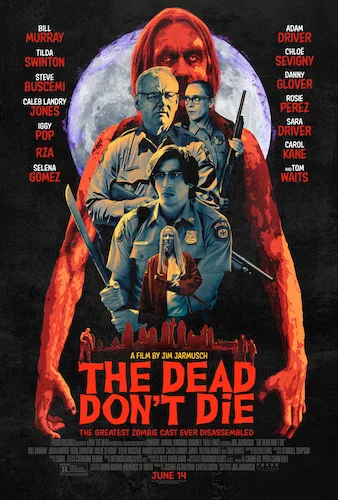

The Dead Don't Die

Jim Jarmusch’s latest oddity film in his peculiar filmography is more of a solid statement than an actual story. The Dead Don’t Die presents a small southern town that is one of the many places on earth affected by a geological shift caused by fracking. The Earth is now thrown off of its usual axis, and it is operating in a new way. Zombies are coming out of their graves. They still bite people, but their cravings aren’t brains. Their groans include “coffee”, “wifi” and various types of candies. These are zombies that fixate on only one obsession at a time, while the world is a big dumpster fire. This is our world. These are our zombies. This is us.

With the undead consumed by materialism and the world run amok, The Dead Don’t Die presents a tried cinematic genre as a commentary on the current blinders people have on. For instance, a zombie walking towards a house is called a “trespasser”, rather than, I don’t know, a literal corpse that is skulking around. It’s these kinds of subtle details that elevate Jarmusch’s statement. This also includes the “finalizing” of a few corpses of young adults that were not zombies yet. A police officer (Chloë Sevigny) questions if this was ethical, since they were only dead humans. The response from other officers was that they were going to be zombies eventually. We attack any signs of opposition in modern times, on the off chance that our victims are going to lean towards one side fully, or do anything we disagree with that poses as a threat to us.

Since The Dead Don’t Die is a stream of tonality like most Jarmusch films (including the jokes, that range from a mental nod to a bit of a chuckle as responses), the importance of his symbolism makes each subsequent scene mysterious. You know how the film will pan out, and how dry each joke will be. What really matters is what he’s going to say about the current political climate next, and how he will convey these messages. Otherwise, the film has a few sour notes (a rarity for one of his works). The main one is the complete underutilization of the film’s self awareness. We get the breaking of the fourth wall in a brilliant way, but we never see what the extra mile is. Why is this gag even here? What does that have to do with capitalist zombies? The idea that fate is foreseeable but unpreventable? Why have the characters acknowledge that they are in a film if you do not go even further? It only makes it seem like Jarmusch is phoning in this joke, and that’s unfair for a director that puts so much work into ever little detail.

The three main police officers stumbling upon gruesome sights.

The second main issue is the character of Zelda, who is brilliantly portrayed by Tilda Swinton, and easily the most interesting character in the entire film. This is someone who has seen this zombie outbreak thing not in films, but in real life. Why does she get handed the most outlandish ending out of the bunch? Clearly, it does make sense on paper, but that doesn’t mean it works chemically with the rest of the film. It’s like enjoying your ice cream sundae, only to find spicy Doritos chips at the bottom. You like these chips, but that doesn’t mean it works with the sundae. It’s a head scratching bow on top of the greatest gift The Dead Don’t Die has to offer.

Zelda preparing for the outbreak.

Otherwise, the self awareness is purposefully on-the-nose. The ending narration spells out the metaphor we already figured out, by insinuating we are the brainless mob currently prowling the cities of the world (well, the film’s not wrong). The climax is a pinch of funny, and a whole cup of heart breaking. These aren’t the usual zombie films where killing your own loved ones is a necessity to survive. It’s witnessing your loved ones being consumed by technology and desires, while the world shuts down around them and they don’t even notice. This is one of those films where I understand why the reception hasn’t been stellar, but I see so much thought and purpose for the way this story was told, that I think it’s still worthy of a recommendation. It may not have all the best results, but every single intention serves a greater cause (including the repetition of Sturgill Simpson’s recorded song for the film; I guess it was meant to unite those that still had conscious thought in an amicable way?). There’s nothing wrong with that. At least this film is trying something different to an exhausted genre, right?

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.