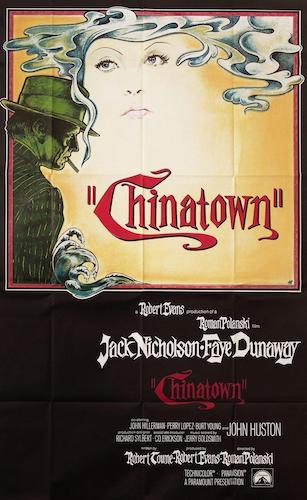

Chinatown: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For June 20th, we are going to have a look at Chinatown.

Last week, we looked at Rosemary's Baby and its branding of the best qualities any Roman Polanski horror could have. This week, we look at something a bit bigger. This is a film that I barely think of as a Polanski film, despite it being his best. This is the kind of film that supersedes being owned by someone. Like many of the biggest innovations or creations (the internet, Coca-Cola, 1984), Chinatown seemingly sprouted legs and carried on its own path by itself. It is a rare film that is so good in virtually every way, it transcends identification. To witness Chinatown is to experience a once-in-a-lifetime event.

We can announce the players and the various teams involved, but there is not one singular element that brought the film to such an iconic stature. You just have to continue after its existence doing other projects, because magnificence like this cannot be captured twice. Hell, Jack Nicholson tried with The Two Jakes, only to churn a mediocre sequel that almost nobody will even consider bringing up. It's like having to choose between Appetite for Destruction and Chinese Democracy eras of Guns N’ Roses to see live. You may not think twice.

Gittes on the start of his hunt.

The film’s origins started as a dream (or the death of one, rather). Films noir were beyond tired around the time of the creation of neo noir. The genre was being reinvented, but revisionist genres have to seal the deal once and for all. The path ahead has to be the only option. Think of Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven and the desecration of old-timey westerns that could no longer hold up after this dismal sendoff. This was accomplished by acknowledging the death of the classic western tropes in the form of a geriatric former outlaw who is forced to take one last gamble with death.

Similarly, we see Detective J.J. Gittes resorted to adultery scandals. That's not what being a noir detective is all about! However, he is confined to this small space for narrative's sake. He even acknowledges the Venetian blinds he just had installed being mishandled (these blinds are a common set piece in films noir). He knows his fate. He just has to keep moving ahead. He dabbled in the unknown before in Chinatown. It did not go well. He has to stick to these low levels of formulaic comfort to not risk everything again. This is what it means to break ground. Succeed, and you're iconic. Fail, and no one will ever remember you. There are slight chances that you will be appreciated later on, but who wants to take those slim odds? Apparently, everyone that worked on Chinatown did.

Gittes sticking his nose where others don’t want him to.

We get a new case, but something doesn't sit quite well. The more Gittes uncovers, the uglier everything gets. In films noir, we find ugly people in grim places. In Chinatown, we find grim people in the ugliest place known as Los Angeles. Evil can only be linked to one person for so long, before we have to admit that the city might be the source of the negativity. With all of the deeply rooted nefarious infrastructures found, Chinatown as a setting went from a bad memory to a safe haven.

So much of Chinatown's mythos is thanks to Robert Towne's work with what is debatably the greatest screenplay of all time. Virtually every single detail makes sense. Every character has an arc to some notable degree. The confusing road arrives at a shocking conclusion. A second viewing proves that all of these turns actually make perfect logistical sense. The only faux-pas Towne made was trying to gift Chinatown a happy ending. Polanski disagreed so vehemently, Towne abandoned the project during the final phases. Polanski went ahead with the cataclysmic climax. It was the only way to kill off old noirs for good. This was about paving a new path, not taking the same highways.

Gittes confronting Mulwray.

We get additional twists that will be burned into your mind for the rest of your life. The final bow is an ending that leaves you speechless once you leave the theatre (or your chair). Nothing is easy after Chinatown. Gittes' guilt is something we carry too. We were warned. We didn't listen. We played with fire for too long. It was all for the greater good, but that didn't stop the worst from happening.

This grey area makes Chinatown special. It's an ambiguity the performers adore working with. Jack Nicholson plays Gittes as a leader who will still listen (even if he is dealing with a wall of lies). Every reply is actually a calculation. Witnessing his thought processes throughout the film is what makes the first viewing so captivating. On subsequent watches, it is Faye Dunaway's pitch perfect performance as Evelyn Mulwray that does the trick. There may never be a dishonest performance this good again. You miss so many cues the first time through, but a more contextual second offering places every single clue Dunaway left us out in the open. It's a subtle performance, but we mistaken it for neutral, when it may be one of the most complex performances of all time.

With the detective and the femme fatale set up, we move ahead into the great unknown. With so much revelation, we still have so many "what if" questions circulating our minds by the end. We see so much, but it's only a taste of how hideous civilization can actually be. The hands of power can grab anything they want, and we see that all too often in Chinatown. People being harassed. Higher ups abusing authority. Lower classes being cheated. Chinatown will forever be relevant when authoritative figures misuse their abilities, and I don't see that problem disappearing anytime soon.

Evelyn Mulwray choosing to be honest (we think).

Chinatown seems like a series of twists, as I've stated before. You can also consider it the results of trickle-down after effects. The major problems in Los Angeles branch off into many different little stems. Gittes started at one tiny end and worked his way back to the trunk of the tree of corruption. There are thousands of other branches that go elsewhere, but we see enough on the one branch we cling to. That's why we have to forget it. We have to forget not just this branch, but every other branch. Chinatown got Gittes into trouble before. This is just a reiteration of Gittes trying to be the hero until the fatal end once again. It didn't work before. This is a reassurance that it will never work. Not for a guy in his position. Not for a worker so low on the totem pole. Not for a generic cinematic character archetype that has to answer to the usual checklists.

Films noir were never the same again. This was not a dark film held back by the Hayes code. This was the full extent. This was a colour film ruined by sepia hues, not taking advantage of the possibilities. This was the same old story venturing off the beaten path, detrimental to all involved. This is what we knew being choked to death before our very eyes. We were left with a new genre in town, that didn't even have rules (let alone play by its own ones). What is even more fascinating is how such a relentless film is still structurally as sound as can be. Anything (including the most disturbing twist of them all) makes sense in the film. Alfred Hitchcock forced a flushing toilet to be shown on screen for the first time in Psycho, because he made it a plot device. Polanski and Towne made similar decisions countless times for Chinatown. We had to experience X, Y and Z, because the story called for them all.

Gittes finding a resolution he’s faced before, slowly seeping in.

With the greatest story ever told in cinematic history, a brooding jazz score, an aged-photograph cinematographical style (that rivals The Godfather), and performances that convinced you of their own lies, Chinatown is a blend of the best of all worlds to the point of pure perfection. You know your favourite meal you have ever had? You cannot pinpoint one ingredient that stuck out? That's this film. Any slight change may have broken the irreplaceable synergy found here.

It's so bizarre that such an unattractive film is so gorgeous in a creative sense. We witness cacophony done on purpose. The majority of the film is hard to witness in varying degrees, yet the entire package is what is legendary. It set a tone for neo noir films to the point that it still has not been surpassed. Sure, we have many other brilliant examples (Mulholland Drive, Blade Runner, L.A. Confidential), but Chinatown exists in its own, self consuming universe; like a detective sitting alone in a dimly lit bar, drowning their sorrows away from the world. There may never be a beautiful tragedy as good as Chinatown ever again.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.