Blade Runner: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For June 25th, we are going to have a look at Blade Runner.

It is without intention that I keep connecting iconic films together through this On-This-Day Thursday category. I hopped from one horror film to another (Poltergeist to Rosemary's Baby), then from Polanski film to Polanski film (Chinatown). We now arrive at another neo noir gem that has never been surpassed. Like Chinatown, I really don't imagine Blade Runner as simply a Ridley Scott film, mainly because there are so many career-best moments happening here. Vangelis crafted one of the best scores ever. The sets, to this day, are mind boggling. I would even argue (feel free to disagree) that we have never seen Harrison Ford better.

Blade Runner is not a completely original idea. It is a stem of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by science fiction revisionist Philip K. Dick. While Dick is the best writer of his kind, and many adaptations of his work are noteworthy, Blade Runner did something a bit different. It deviated greatly from Dick's work, knowing that his genius cannot be perfectly replicated. Like a rogue replicant, Blade Runner started from an innovation, and set it's own destiny. Blade Runner became singular. Dick's spirit is felt through out, but a bigger picture was implemented.

Perception plays a major theme throughout the entire film.

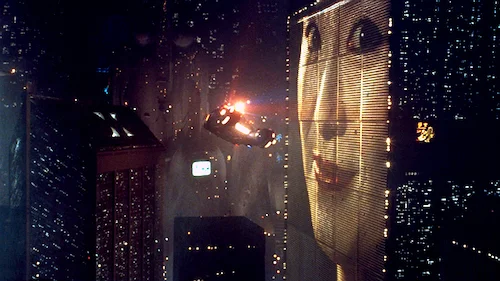

What is the mythos that makes this film truly something? Perhaps it's the philosophy that matches the scope. The gigantic buildings do not diminish the story, when it is the narrative that is the largest. Depending on which of the billion variations of this film you watch, you may get some sort of back story at the start of the film. Whether you did or didn't, the environment says enough. The lights and colours are all futuristic, but the smog is pungent and the garbage rises off the screen. This is a dismal future, but it is still all too familiar. Androids fight for their freedom and ability to live. For what? This hell hole? We all deserve the right to exist, but life in Blade Runner is such a clustered misery.

Deckard is an agent that chases after dreams; particularly that of a unicorn. His job is to end lives, and yet he hopes for another life. He finds release through a replicant named Rachel; as an expert blade runner (a detective that eliminates anarchistic replicants), he knows she is an android right away, yet he remains in awe of her. Call her a femme fatale, only because this is a neo noir, but I wouldn’t consider hope to be the downfall of the lead detective. Does hope make him second guess his missions? Absolutely. Does that make Deckard a worse person? It actually adds life to him, like a cyborg having come to life.

Rick Deckard being the perceiver of real and fake (despite experiencing grey areas himself).

The notion of free will gets shattered into pieces once we get asked the most important question: is Deckard a replicant? Having this question be open ended makes Blade Runner all the more impressionable. What do you want him to be? For me, there’s no question: the guy is a replicant. How could his dreams be read by Gaff? He never told anyone about his unicorn dreams, so where did this sign come from? His memories could easily have been implanted, because he is a replicant. Yet, you can argue that Gaff and many others share the same dream as Deckard.

“It’s too bad she won’t live. Then again, who does?” is the legendary line Gaff leaves us with. Again, New Los Angeles is a disaster from intersection to intersection. People are stuck between one advertisement and another: which product out of these two do you want? Is that freedom of choice? I suppose it’s better than nothing. Sadly, that’s the compromise we all make daily. We have to abide by these stipulations that surpass even a moral compass (what’s ethical about being forced to select between licensed corporate products?). Like the people in Blade Runner, we are happy enough to be stuck. At least we’re not replicants. At least we’re not dead. Why can’t the replicants live, on that note?

Los Angeles is an advertisement-clad, despotic heaven.

When we hear about the tears in rain (from lead replicant Roy Batty), we see a vulnerability. We feared the replicants this entire time, likely because they were violent. They were freedom fighters, dying for the worth of future replicants to experience true life no matter how they were conceived. Batty tries to cling onto memories in his dying moments, yet the flurry of everything will make you lose your grasp, like a free falling item you wish to save but cannot. These are the tears in rain. Significance is lost. It was all stripped away from Batty. He welcomes death, only because his life was turned into the antonym of just that.

Why does Deckard get a free pass? Is it because he is not explicitly a replicant? Is it worth letting a possible replicant experience life, when we are all dead on the inside? Is the slight life of a replicant the same as the heavy, existential void the living feed every day? Blade Runner is cold, but it is very aware of what it is saying about self fulfilment. We fight to survive for scarce meals in crowded asphalt cells, underneath neon stars and acidic smog clouds in the nighttime sky. At least we got to do so.

Roy Batty accepting his fate after experiencing life, even for a little bit.

We can even begin to wonder why replicants exist. Did we think humanity would do better in beings we create? Is that why children are bred? Do we wish for something better in the lives we create? Surely that is not why many people you know have kids, but in Blade Runner, that is why we love, why we create, and why we withstand it all. We love partners we wish to go further. We create lives that can do it better. We withstand to make sure our wishes for them were fulfilled.

It’s so sad to see the hopes of creators being crushed by a bureau. Replicants cannot exist for a long enough time period, because they have become too sentient and undetectable amongst humans. So what? They only got violent, because they were being stripped of their short term lives. They were created for that very purpose. Why rid them of this capability? As if that makes humanity better.

Rachel surviving within a closed, safe, richly gold haven.

The sun exists, and we see it very scarcely in the film. When we enter the homes of the elite, high above the ground, we notice the warmth around us. Most of the film is a dark, chilling blue, because we are almost exclusively forced to stay on the murky ground. Vangelis’ score is a synthetic orchestra: a robotic interpretation of human moods. At the end of the day, we all want to feel. We get the sun for a few seconds. Maybe that was enough for us. Maybe those are the memories Batty tried to savour. Blade Runner features a (then) future where the artificial is slaughtered if it tried to become real. The true purpose of the film is to understand that reality is complex, and artificiality can mean something if you want it. Deckard chases after replicants, only because he’s really chasing after the reality he hoped for growing up; not this dismal swamp known as the real world.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.