Acting Lesson 1: A General Overview

Look. The art of acting is such a huge area to cover, so one piece cannot do it true justice. Where do we start, though? Do we look at powerful monologues, or funny skits? Do we observe the cinema of the world, and see the ripple effects of certain performances? I think we need to start at the barest of basics: what acting means through many different phases of cinema. If we are analyzing acting in film, we must take into account how film has evolved over the years. To the common viewer, film has had a few shifts but has remained one true form for decades. I would argue that is actually not the case. If you dig deeper, you can find that film has changed significantly even in the last twenty years. One of the biggest identifiers is how the purpose of acting has slowly pivoted away from where film was at even not that long ago.

What is the purpose of acting? It might be a stupid question, but it’s important to start from scratch if we are covering the barest of basics. The easy answer is to insist that performances bring characters to life, right? These can be biographical figures, created fictional beings, or amalgamations of the two. I will also focus more on biographical performances, and character acting for other articles, so don’t expect the specificities of those here. Instead, this is like meditation: you cannot rush the process. You have to start at the core, and work your way out. To reflect back on the previous question (what does acting do), I would argue that there are many purposes. Acting can inflict a specific tone a film requires. Acting can create an identification between written words and an audience, since a human element has created a bridge between the two. At the end of the day, acting — more or less — is the delivery of messages. Depending on where in history we are, these messages can be represented in differing ways (as we will go over). A film puts together so many other forms of communication, but acting almost feels like the last say. A cut starts a shot. Lighting seeps into the shot. Costumes, sets, and props all make their way at the exact split second. A character blesses us with their presence. It is their delivery that flows through a scene, and usually punctuates a scene right before the next dialogue cue or cut. This is why acting is such a recognizable aspect of cinema for many. It’s the carrying of words, symbols, metaphors, jokes, and pathos from filmmakers to their audiences. It is the most direct form of these kinds of communications. It is the most easily recognizable.

This purpose has been prevalent throughout film history, but the ways in which this purpose gets carried out have changed extremely frequently. This is why diving into an older film may create a disconnect for casual film viewers (ones who may be more comfortable with recent works). Why can a stone faced noir detective be as fantastic as a modern day superstar that learned how to build a house to get into character? Well, different styles call for different protocol. Different eras had different methods. I hope this article guides you through a very basic journey through the many tides of cinema, so you can recognize why acting was the way that it was, and perhaps how we got to each following step.

Workers Leaving the Factory (1895)

The very first films were the documentation of real life events, or the recreation of familiar activities. The capturing of life in moving pictures was a new concept towards the end of the nineteenth century, and the niche was seeing the familiar in a whole new way. Innovators like the Lumière brothers specialized in bringing everyday occurrences to film. In a lot of these early shorts, these scenes are actually recreated, as opposed to real instances being captured. Due to the fickleness of filming, these kinds of scenes were shot again and again, to ensure that at least one take would work. Films were shown at events like carnivals, for the middle and lower classes to admire (the upper class scoffed at the idea, reportedly). Acting was not a brand new concept. Theatre had long since left its mark on society. This is just how it was in the earliest days of film.

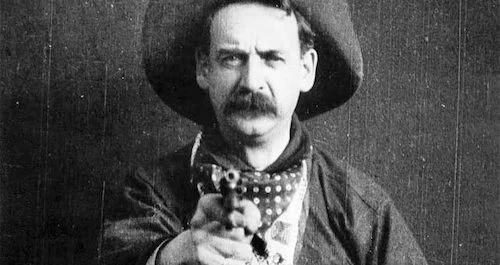

As film evolved into more of a narrative medium, acting had to change along with it. Seeing as theatre acting was beyond embedded into many cultures worldwide by this point, there was clearly an obvious answer as to how cinematic acting should be carried out. With static cameras, barely any chances to pan at all (if any), and no sound recording, the earliest narrative films played out almost like little stage productions. In the extremely-reliable examples found in The Great Train Robbery, you can spot characters leaving one side of the screen at various points, as they obey the “exit stage right” rule on these sets, as well. It may not make entire sense in the scene now, but it was an obvious choice at the time.

The Great Train Robbery (1903)

You will even find trap doors, and “dead” characters rolling off the set, as if this where a stage production. The Great Train Robbery also includes outdoor scenes, and in this way it is a nice example, as there is obviously no form of a stage here. Despite sticking with the rules that the theatre world migrated over into the cinematic narrative, there is a bit of a breathing room, here; a sign of promise. With enough innovation, we can take this storytelling device to new places.

Obviously, no sound means no dialogue delivery, so that is one major disconnect film had with theatre. Title cards were used, but feelings still had to be conveyed. The extreme facial expressions are partially theatre inspired: the people at the back had to be able to sense your pains, too. Film definitely exacerbated the grotesqueness of these expressions. Faces were framed and close enough. You can argue that most silent era film performances have extreme facial movements, but there is a definite roughness this early on.

The silent era started to clean some things up, when it comes to the identity of cinema. Feature length films were being created. Editing and camera techniques were being invented. Film was beginning to grow its wings, and find a way to separate itself from theatre for good (depending on how you look at it). Recorded sound was still not around (although films with sound recordings can be traced to way earlier than the 1927 mainstream distribution date). This meant that films still had to rely on the power that performances could bring to their scenes: faces had to match title cards, and emotions had to match orchestral cues.

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

The German expressionist movement was an early game changer, as the gaudiness of cinematic acting was fully embraced. Many of these early examples were horror films that hyperbolized sets, costumes, make up, and, you guessed it, acting. This slowly seeped into the less-horrific works like the groundbreaking Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. While an important film for many other reasons (mostly sound related), Sunrise is still a great example of a more serious acting effort; it encompasses the theatrics of German expressionism, whilst settling for a more neutral tone, too.

The camera creeps closer to its victims by zooming, now. Panning exists, too. No longer did faces have to scream in order to be heard. There is still a long ways to go, when it comes to subtlety, but some significant progress has already been made on this front.

What would encourage this growth to continue? The actual inclusion of recorded sound, of course! You can find many examples of films that maybe didn’t know how to implement this massive change right away; thus, you can find a plethora of unintentionally funny examples of wonky projection, terrible annunciation, and the like. Singin’ in the Rain brings up this concern light heartedly. However, with all of that in mind, the transition also wasn’t as terrible as you may think. Some newer silent stars (Greta Garbo is a strong example) leapt into the new world effortlessly (in terms of her work). It was a major adjustment (we will discuss more about the evolution of sound in another article), and a great divide could be found in how performances commenced from then on.

Baby Face (1933)

During the precode era, Barbara Stanwyck left her mark. Not a stranger to acting, Stanwyck was a Broadway success previously. Stanwyck was special, because she is one of the notable performers that understood how to minimize maximalism. In this scene from Baby Face, pay attention to Stanwyck’s more anchored performance, compared to the mug-heavy work of her costar. People like Stanwyck introduced another theatrical element to combat the over-reliance that film had on theatre (oddly enough): projecting to the audience. Stanwyck knew that the audience was not miles away. It was the camera and the microphone; she allowed these devices to pick up her work, and do the heavy lifting for her. This is an early, stunning example of nuance in cinematic acting.

Many performers followed suit, after gifted actors like Stanwyck showed them the possibilities. Film was taking form, and many genres were starting to branch out into their own territories. This was the start of the Golden Age of Hollywood: the recreation of what a performance artist could be, and how they can connect with their audiences. Theatre helped with more ambitious acting, too. How could we showcase more, without dipping back into the overacting territory? Enter a prime example: Laurence Olivier. Olivier studied acting academically at the Central School of Speech Training and Dramatic Art, followed by his time at the Birmingham Repertory Company. Of course, Olivier was a prolific stage actor, as well.

Hamlet (1948)

Olivier starred in a number of works, before directing himself in Hamlet (the only William Shakespeare adaptation to ever win the Academy Award for Best Picture). This is a great example that not only showcases where acting is heading, but the distance of how far it has gone, too. Note how this scene focuses on Hamlet’s psychological state, more than his physical wellbeing. This was obviously not a discovery for a Shakespeare play, as these works have been adapted in countless ways and means. Yet, this is a noticeable advantage that cinema had. Olivier knew that the camera was his audience, and he allowed that short distance to pick up on more than just the words he was delivering.

As Olivier was perfecting traditional forms of theatrical and cinematic acting, there was the spark of a new style around the same time. What Olivier was doing can be considered the “art of representation”: the ability to convey emotions and thoughts in an understandable way. Konstantin Stanislavski was a theatre mastermind from Russia that had been working on the “art of experience” from way before (as early as 1911). The “art of experience” was having the performer truly live these moments to project an untouchable connection; one of true purity, and not of artistic objectification. Stella Adler is likely his most well known pupil, as she studied under him at the Group Theatre in New York. She then created her own Stella Adler Studio of Acting in 1949. This was only after she had dabbled in method acting alongside Lee Strasberg (considered the originator of that style). Adler found a happy medium in the middle, where Strasberg enforced the importance of commitment. Strasberg founded the Actors Studio in 1947.

On The Waterfront (1954)

Bringing up both Adler and Strasberg makes sense. You had devoted disciples of either teacher (Adler’s alumni include Robert De Niro and Kate Mulgrew, whereas Strasberg’s class includes Ellen Burstyn and Dustin Hoffman). You also had mutts: actors that were involved with both teachers, and either learned from both or leaned more towards one side. An example of the latter is Marlon Brando, who changed the rules of acting within one powerful performance alone: Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront. You can actually see Brando “thinking” like his character throughout this film. This was no longer an artistic medium that created moods. This was a perception of reality. Brando claims that Strasberg had no effect on him, and this early performance does replicate more of Adler’s philosophies to be fair. However, Brando would later go on to represent method acting in at least some partial ways. For now, we have a scene between Brando and Eva Marie Saint consisting of friendly conversation. Observe how each and every line delivered by Brando serves a brand new purpose. One line is a means to find out more about his new friend. Another line is a self conscious doubt of himself. The following line is a jogging mind. Every line is a brand new idea, and it’s still exhilarating to witness.

The days of Shakespearean and theatrical influence are not gone, though. Instead, the passion and spirit of these works were slowly seeping into the newly developed screen styles that were gradually making their way onto the big screen. Many epic films were dominating box offices, including the remake of Ben-Hur (featuring a booming Charlton Heston). With the ways that cinema whats evolving, ambitious monologues and devastating tales were being showcased in brand new ways. Intense angles. Angelic scores. Exciting editing. Everything was being used to turn these euphorias into fully fledged experiences.

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

The best example of the theatrical side of acting meeting the newly nuanced side is through Peter O’Toole’s bravura performance as T. E. Lawrence (in Lawrence of Arabia). He starts off comedically, as a klutzy cartographer granted the opportunity to take part in political (and wartime) affairs. Keep in mind, by this time, cinema was a fully fledged story telling device that incorporated many narrative must-haves (including character arcs), so O’Toole’s slowly-progressing character work was astounding in its own right. Yet, O’Toole knew how to mix both the minimalistic realism of the way, with the effective booming of the old way. In this scene below, you can see a shaken up and malnourished Lawrence still command the shot through his theatrical voice, yet he exhibits every proper sign physically. He embodies both sides of acting (at that point) in one, pitch perfect performance.

It was a great transitional role, and a major bridge for the students of Adler and Strasberg to cross. Dustin Hoffman (a Strasberg prodigy) was far from the first method actor, but he was definitely a startling early example (especially when it comes to actors that go overboard with their dedication). To put his divergence into perspective, Hoffman worked with one of the game changers on this list: Sir Laurence Olivier. While working together on Marathon Man in 1976 (not that much later than Midnight Cowboy in 1969), Hoffman stayed up many hours to replicate the sleeplessness of his character. Olivier uttered the now-famous response “My dear boy, why don’t you just try acting?”. Clearly, the disconnect was still strong at this point.

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

That same divide can be found in an almost miraculous way in Midnight Cowboy. You notice Jon Voight’s performance is a little more earlier Hollywood in comparison (by earlier, I mean ‘50s, but not the golden years). Hoffman’s “Rats” is a fully physical test of endurance. He throws his entire body into every limping step. He forces himself to remain this character for as long as he needs to (some method actors remain in character even when the cameras are not rolling). This is not a means to decide which performance between the two is better, but rather a nice display of differing styles that compliment one another greatly.

Method acting certainly made sense with the end of the Hollywood code. The end of forbidding rules goes hand-in-hand with shocking acting practices. Method acting wasn’t as engrossing as it was going to be, but it was well on its way by this point. With that in mind, we were beginning to see a major shift in styles. Actors were forcing themselves to live these lives, and these lives were now getting less familiar. This is the earliest form of acting as we know it now, because so many defining factors were playing together at once.

The Godfather (1972)

We spot Marlon Brando again, but this time he has appeared to go down more of the method route, despite never being fully method. For instance, this is about the time he began to notoriously refuse to memorize his lines, and have actors or crew members hold up cue cards for him. Maybe it’s because he put dedication in so many other parts of his performance. This includes the stuffing of cotton balls into his mouth during an audition (he was later provided with a mouth piece), giving him a saggy-faced scowl and the voice of a worn out criminal overlord. Considering that Brando was not that much older than his sons in the film (including Al Pacino), you can see how much effort went into the self-aging process for Don Corleone.

Many actors were beginning to follow similar paths. This is also likely because of these performer’s own studious upbringings. An example is how Herbert Berghof worked alongside Lee Strasberg before starting his own institution (HB Studio). HB Studio had a lot of crossover students (yet another school Marlon Brando was a part of, as well as previously mentioned students like De Niro), but it was also the starting place for some specific icons. Jessica Lange pursued photography and modelling, but her primary acting experience came from the HB Studio.

Frances (1982)

While she had a bit of a slower start into film, she never gave up on trying to achieve this dream. When discussing her future projects with Andy Warhol for Interview, Lange even took note of how she still felt that she had ground to cover, and that her Frances Farmer performance was one she felt could help get her there. That role ended up being the titular character in Frances: one of the definitive performances of all time. Even the conversational moments — like the scene below — insist an early Brando style, but also something of the new style, too.

These slight hints ended up becoming harbingers for Lange’s more dramatic moments in the film, which verge on being hyper realistic. The line between theatrically-powerful and realistically frightening was beginning to disappear. The hunt for something real was the end game for many different acting styles; no matter how separate they wished to be, their influences rubbed off on one another, providing a converged series of results.

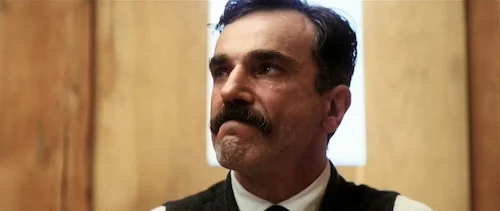

My Left Foot (1989)

This is where it gets very interesting. Daniel Day-Lewis is one of the most regarded full-on method actors of all time. He has gotten sick because he refused modern day medicine for period piece shoots. He was fully invested in his work to the point of absurdity. He studied at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School when he was younger, which, believe it or not, was founded by acting purist Sir Laurence Olivier. Nonetheless, Day-Lewis’ extreme immersion is hard to ignore, and it has set a course of path for many current actors. In My Left Foot, you can see how Day-Lewis plays Christy Brown — an artist with cerebral palsy — with an intense focus on the physical embodiment. Yet, perhaps due to his Bristol Old Vic experience, you still get signs of theatrical dominance. This was the distribution of the unobtainable performance art, to the world we knew: the ultimate push of the dramatic arts.

Film was making its way onto television in the form of the miniseries. Subsequently, the independent film circuit was pushing forwards as its own viable market. Still, we had many performances that played by the rules of the now-countless waves and styles. Method acting was beyond common. Practical acting was still alive and well. A blending of the two usually got followed by awards nominations earlier the next year. Mainstream cinema was passionate, but it was finally starting to get into new territory: CGI was a new element that could implement many previously-unattainable ideas (acting with prosthetic makeup, and with motion capture will be covered in a separate article).

Monster (2003)

Extreme dedication can be found in the Charlie Theron performance of serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Monster. Make up played a major contribution to this role, but Theron’s method work brought the prosthetics to another echelon. This is the continuation of method acting many years later: a testament to the earlier cinematic successes.

However, acting was also starting to work small. Between the shift to the small screen (television), smaller budgeted productions (indies), and even the incorporation of special effects, many ideas were being done in a more nuanced way. This also calls for more introspective acting. A prime example is Kate Winslet’s work in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Clementine is eccentric, but she is still a believable person. She is also mimicking the inner dialogue of lead character Joel’s departing thoughts. If you think about it, there is a major separation between this kind of performance, and the many earlier examples. Cinema was able to dig into something deeper, and acting was able to go along with it. Just see the following example, and think about whether or not you would find this kind of delivery back in the ‘50s; hell, even the ‘80s would be a bit of a stretch.

This delicate style of introspection is, of course, not new. We were seeing that in performances before: even in Marlon Brando’s Malloy scene featured earlier. This kind of reflection was beginning to resonate on a mainstream level, though. Even though there were obviously blips of it before, this was something that lingered more in the arthouse and world films. In the Hollywood mainstream, independent cinema was finally making a dent big enough to make you wonder what independent cinema really means. That’s a discussion for another day.

There Will Be Blood (2007)

For now, you can see how method acting no longer had to resemble extremities. It can be smaller scale, too. That last point may be a bit of an anomaly here, seeing as Day-Lewis will forever be a commanding-style of a performer. This is as subtle as we can get with him. In There Will Be Blood, the all-in style of method acting created a whole new character that was full of his own quirks and mannerisms. Now that acting is borderline virtually ruleless, so many liberties can be had with a performance like this, and an idiosyncratic character like Daniel Plainview can live in powerful, signature moments like the one below.

We will end off with a few recent, intriguing examples.

Happy-Go-Lucky (2008)

Sally Hawkins’ comedic turn in Happy-Go-Lucky is an interestingly different style of acting, where much of her character is played off in a reactionary way, as opposed to the dominating way. This also does not make quite that much sense, given that she dictates literally every scene. Pay close attention, though: everything she does, especially in the scene below, is a response, more than an instigation. This is a great example of Adler’s style of acting, where a character is experiencing the moment, rather than painting it. (Comedic acting as a whole will be analyzed in another article).

Blue Jasmine (2013)

Cate Blanchett in Blue Jasmine employs a very old-Hollywood type of performance, that brings out the original qualities that dictated the golden age. Maybe it’s Woody Allen’s fixation with the stage (and his theatre-aware screenplays) that has brought this out. Maybe it’s Blanchett’s awareness of how much domination is required at any given moment. Regardless, this is a refreshingly classic style of performance that you may bump into every now and then.

The Revenant (2015)

Then you will find many method performances. I find Leonardo DiCaprio’s take in The Revenant oddly under appreciated. Sure, you can point out the obvious with the amount of torture DiCaprio put himself through (freezing weather conditions, difficult scenes to shoot, the like). Moments like the one below are often overlooked in these kinds of discussions. Here, every previous scene is clearly embedded in his core, as he is shaken up and shivering with vengeance (and a little bit of cold, sure). This is the extreme focus on subtlety: the two polar ends of method acting found in a performance like this one.

Acting will continue to evolve, but we are at a point where it is now cyclical. Nicolas Cage has claimed that German expressionist films are his inspiration, for instance. That has to mean something. His exaggerated movements now make perfect sense. We can reflect on the past, and decide on what we will do in the moment. We don’t have to have differing styles in a negative way. There have clearly been successes within each acting pool. At the end of the day, over one hundred years since the earliest instances found here, it’s all subjective now. Is acting about the little details that make a character human? Is it about going all out, and putting all of your heart and soul into grinding yourself into the ground? Is it about taking charge of a scene, and making written words leap off the screen? Is it about using what little you have to go the distance? Hopefully, this article has shown that it can be all of these things. Preferences can be had, but context creates a bigger picture.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.