The Death and Life of John F. Donovan

The Death and Life of John F. Donovan was slated for a 2017 release. Xavier Dolan’s English language debut had a huge line up, and a crazy premise. An actor gets in tough with a child fan, and they both identify as gay during a time of intolerance in the not-so-distant past (the ‘90s); slanted reporters (one played by Jessica Chastain) twist the story towards a malicious interpretation, and it resorts in the child — now an adult — recounting the ordeal to a journalist in the new millennium. Part of this is semi autobiographical: Dolan personally wrote a letter of appreciation to Leonardo DiCaprio, hoping to spark a correspondence with the actor. This is that dream going the wrong direction. This is too much happening. This is a brilliant premise.

But it all went south. Dolan cut many notable names (Chastain, Nicholas Hoult, Taylor Kitsch, amongst others), and took out many story elements, too (the media influence was downplayed significantly). The film was pushed to 2018, then to 2018’s festival circuit (TIFF, mainly) with hopes for a 2019 wide release (or a late 2018 awards race push). I am writing this review now, on the announcement that the film will finally show in Italy: the second wide release outside of France. This is likely the best it’s gonna get, folks. It’s 2019, and it’s barely being released. Dolan’s latest film Matthias & Maxime has premiered at Cannes already, as if to try and push past the fact that this film exists.

Actor John F. Donovan battling many parts of his public and private life.

What the hell happened? Well, it’s actually pretty easy to see. The Death and Life of John F. Donovan was overworked on, to the point of sterility. Not only that, but it encourages all of Dolan’s signature traits to the point of obliteration. For instance, Dolan loves injecting his playlists into his films. Many directors do. Dolan listens to very mainstream songs, though. This leaves for a very on-the-nose response for each scene that he tries this with. In Mommy, for instance, Lana Del Rey’s “Born to Die” tops off the finale to a highly melodramatic effect. The ride up until that point is riveting, and arguably already a highlight within Canadian cinema. You can excuse how literal, and obvious this is, because it feels like the final word (and we hear it loud and clear).

In Donovan, we are graced with these kinds of songs on a blatant basis. An example of a song that will get a pass from me: including Blink-182’s “Adam’s Song” near the beginning is a slight commentary on fan culture (allegedly, the song is dedicated to a fan of the band that commit suicide, and the song is played when fan Rupert Turner is cheering for his favourite actor). It’s a nice touch that is a typical song, but used nicely (as nicely as it can be, anyway). A bad example? Ending a film in 2019 (or 2018, or 2017) with “Bittersweet Symphony”. The only good thing here, is that The Verve have won their rights back for the song (about time), and perhaps the few people that have never heard this song before will now support it on Spotify (or something). It’s like playing Rocky or Chariots of Fire scores during your high school computer class project during a running scene. There are just some things that are so overdone or obvious, that they should not be attempted.

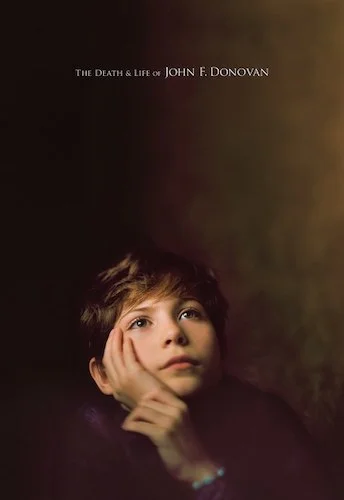

A young Rupert Turner waiting to hear back from his favourite actor.

That surface level of depth turns into a high amount of obnoxiousness, and it rings true for pretty much most of the film. The negative energy we get from an adult Rupert and the journalist interviewing him is highly uncalled for; we virtually do not care about her change of heart as the film goes on, because there is zero reason to be so hateful in the first place. That negativity works in Mommy. This is a theorized world that Dolan crafted, where everyone is on edge. You don’t get that sense, here, and that might be because so much of the film was cut out. Maybe that journalist was so mean, because there was a great big scandal involving the child fan (as was intended to be blown out of proportion by Chastain’s character). Here, she just seems ungrateful with life (“oh boy, I gotta interview some stupid fan with a book”). You can cut story elements out, only if the story works without them. Here, they do not.

We also have selfish family members (Rupert’s mother being an example). The bullies at school make sense; they resemble bigotry towards homosexuality during the most recent grossly intolerant years in history. For Rupert’s mom to be so oblivious to the point of no repair just doesn’t work. There is no true redemption with anything that happens in the film, with any character. This is such an interesting premise; I don’t want to have to hate everyone within it.

Rupert’s mother finding something meaningful in his bedroom.

I want to defend this film, because its intentions are so pure. I just cannot. This is a great melody that has over production to the point of clipping. This is a cake that has just too much frosting on it. This is a painting where the artist was overly obsessed with the colour blue (kicker: it’s a realist painting of a family portrait). This is trying to do too much of a good thing. The twist: The good thing was actually not good to begin with. The melodrama does not work with a weak foundation. The premise does not work without it being carried out. The entire film collapses, because all of the artificial hate stayed afloat on top, and all of the heart was taken out in the scenes that were left on the cutting room floor.

In the end, all we have is an actor that communicates with a fan through letters, then stops when it gets only a little embarrassing. Where is the boldness there? This is a film that is dealing with the death of the actor. It’s the main premise. It’s in the freaking title. The actor stops talking to his biggest fan because he’s slightly embarrassed. The boldness of the film’s title, and the candidness of the promotional posters (all headshots of the cast in a deep state of contemplation) are truly the best parts about this film. The lead up promised something raw, something real. We get one of the deepest premises of the decade, and it becomes a sugar coated take on celebrity culture, and barely any true commentary on an everyday civilian and their superstar friend that both have to take on the same battle against societal intolerance. Let’s not forget that everyone on this trip is unlikeable. Being let down by Donovan is a complete understatement.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.