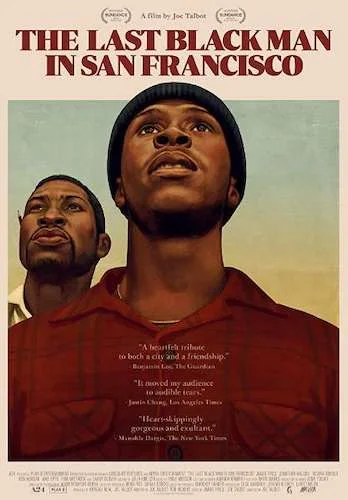

The Last Black Man in San Francisco

Two films came to mind while I was watching the singular The Last Black Man in San Francisco: Synecdoche, New York, and The Truman Show. The former film deals with a metaphysical reflection of self, symbolized by gigantic auditoriums, a house that is permanently burning, and a never ending stage production. The latter film features a memorable climax that shatters the perception of one’s surroundings: a stairway made of clouds. In San Francisco, there is a shot that reminds me of that stairway: a rowboat fighting against a slight current in front of the Golden Gate bridge. As for New York, we have the house that performs similarly as a character, plus the many themes of fighting to stay prevalent. New York fought against existentialism. San Francisco fights against prevailing, instilled race politics.

In case it was not obvious, there is something very Charlie Kaufman-esque about San Francisco, as if we are watching a romanticized hyperbole of life. We start off with a bizarre picture: a caucasian worker in a hazmat suit, surrounded by African Americans dressed as is. A street preacher questions why this is. We already get vibes of a grotesque universe. This is an exaggeration, ala Her, Brazil, or some other depiction of our reality through an obscured lens. The sad reality is, it actually isn’t. San Francisco does toy around with perception, enough to seem fictitious, yet there is actually no real clear indication of anything in the film that this is meant to be that way. None. The fighting against the current in the rowboat is shot in a way that looks like it came out of a storybook, thus making it seem fantastical. Yet, if we really break it down, it’s literally just a character rowing. No hyper aware artificial intelligence to fall in love with. No satire on a 1984 world. No virtual impossibilities. That’s the kicker: there are no impossibilities, here. That’s the scary truth.

Jimmie Fails starring as a fictionalized version of himself.

Who knows what went on when filmmaker Joe Talbot (with his feature length debut) and writer Jimmie Fails concocted this screenplay. Fails based the story on himself. He lived in his grandfather’s home until he was three, and the house was foreclosed on. This was his grandfather’s house, and yet he was sent to foster care. A company bought the house, and left it dead on the inside, when a struggling family could have been taken care of inside of it. It’s a terrible reality many people struggle with today. Making ends meet is not even a possibility for some. That’s a major role in San Francisco: the goal of gentrification burning those that do not meet the requirements to live. Don’t we all get that right?

Fails stars as a fictionalized version of himself, perhaps as a means to have discussions out loud that he conjured up his entire youth. In this story, the house was built by his grandfather (or so is claimed), and it is currently left idle amidst a squabble between homeowners. Fails and his buddy Montgomery Allen (Jonathan Majors) seize this opportunity. They took care of the outside (trying to pride the work of Fails’ grandfather, while the current homeowners neglect it) by painting the exterior and taking care of yard work. Now, they can populate the interior with furniture, appliances, and love.

Fails and Allen waving off onlookers.

There are many ongoings that turn San Francisco into a non-confined work of poetry: a one-person play geared for two parts, the ramblings of a street prophet, and the shared conversations in between. San Francisco almost feels suited for the stage, but Talbot’s direction turns the story into a living diorama. The shots either emphasize the inside of the barren household, or smush the walls of another living capacity. When it comes to outside shots, houses are turned into doll models, almost dwarfing how much space they take in the grand scheme of things. Does it matter that two broke individuals take up this tiny lot? Can’t those that struggle be given a slight break?

”You cannot hate San Francisco, unless you love it.” is a candidate for movie line of the year. Fails brings this up in a time of dire straights, when his loved ones try to extinguish his woes by claiming the city sucks. It doesn’t, though. Not to Fails. He fights for the house, partially because he loves where it is placed. There is no right to hate one’s stomping grounds outright. According to Fails, a level of betrayal has to take place. He loves San Francisco, but it does not love him. That’s why he hates it. He did everything to love it, so it’s only time to turn once every possibility is exhausted.

A sensational shot of Fails rowing across San Francisco Bay.

I don’t even know where to begin with the components of the film. The score by Emile Mosseri is to die for, and the churning of Californian ballads into new renditions (or featuring them at all) is a brilliant reminder of the importance of this city to Fails (including covers of “San Francisco” by Scott McKenzie, and “California” and “River” by Joni Mitchell, the latter being a Canadian-turned-California inhabitant). All of the performances are exactly what they need to be, but major kudos goes to a brave turn by Fails (facing his demons), and a balancing act by Majors (including his theatrical work featured here). It’s almost arbitrary to focus on each separate element, because San Francisco is such an ambitious experience. From the first second, between the initial shot and the musical cue, you know this is an event waiting to take off.

And it does. It remains confined in its small spaces, but that’s part of the brilliance. This is not a stage play, nor is it a mental fantasy. This is a true story turned into a cinematic metaphor, even though none of the elements are offbeat enough to ring untrue. You kind of wait for the moment where things take a deeply fictitious turn, like how Sorry to Bother You changes from a work of satirical symbolism, into an absolute allegorical freak out. Here, no such moment ever happens. It isn’t a let down, either. It’s almost the tearing of your heart. It’s your mind telling you “this never happens, because x, y, and z possibility will happen any second now”, and it never gets proven right. It’s a lie we tell ourselves every time we shrug off someone in need, as we insist “they will be okay”. Everyone shrugs them off. They won’t be okay. That’s the sad reality. Some people genuinely need help, and our turning-of-a-blind-eye is as much justification that they won’t get help, as it is a sign that they will get help. We don’t see what happens, so they can be saved. They can also not be saved.

Fails peering into the house through a foggy window: a distorted depiction of home.

Allen quarrels with Fails in a climactic scene about what a home represents, and whether or not four walls can define a person. Fails allowed four walls to make him who he is in The Last Black Man in San Francisco. This film, and Fails’ co-written screenplay, may have been his way of making peace with the fact that a house does not define a person. His character discovers this, because he has done so in real life. San Francisco is a harsh realization turned into a living poem, and it is the most exhilarating, poignant film of 2019 thus far. This is the kind of film that can be missed on your radar, because of its humble release and dodging of the usual awards season dates. Don’t let it be missed. It’s an event that seems to compete with the best of the year for half the duration. The latter half? It’s the proof that The Last Black Man in San Francisco is the most beautiful film you’ve seen in quite some time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.