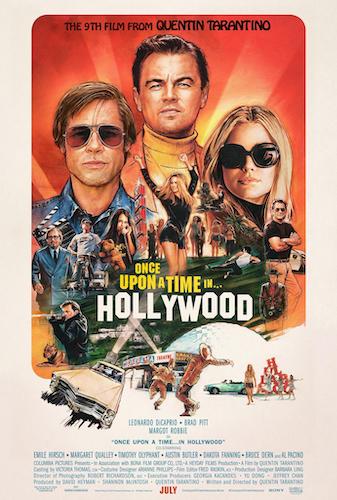

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Quentin Tarantino definitely speaks through his films. The ending of Inglorious Basterds has a leading character declare “I think this may be my masterpiece” as one of the final lines. The title card “Directed and Written by Quentin Tarantino” sharply appears. It’s not subtle. This is how he felt about Basterds (at the time anyway). A few years later, Tarantino received the first lukewarm response to any major feature (so we’re excluding Death Proof, and we’re certainly avoiding Four Rooms) with The Hateful Eight. It felt like he was starting to become a slight parody of himself, amongst the monologues that went nowhere (but finally began to feel worn out), the edge, and the ambition; one cannot fault ambition, but with Eight, it was starting to feel like Tarantino did what he did, because he could (not for any other reason). After Django Unchained (a much better film), it felt a little bit like doomsday. Eight is still a good film, but Tarantino always prophesied that he would end after ten features, only now it felt like he would burn out by then.

Cut to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, where lead character Rick Dalton begins to tear up in front of a child costar. He is reading a Western novel on set, where a lonesome cowboy begins to deteriorate and recognize that his time is quickly approaching. Dalton recognizes this quality in himself. After Eight, it’s entirely possible that Tarantino was beginning to see these signs in himself. He used to want to quit after ten films with a bang. He’s starting to feel the well run dry. Before, he would claim he would win two more Academy Awards for Best Original Screenplay (he has already won two for Pulp Fiction and Django Unchained), so the award would be nicknamed “The Quentin”. This is a humbled Tarantino that we’re seeing in Hollywood. He may even quit after this very film, so long as it is his final hurrah as he dreams. A lot has happened in the last few years, between Eight, the Harvey Weinstein scandal, and the resurrection of that moment on the Kill Bill set. The auteur that was once the Kanye West of Hollywood is now taking a step back, and he does so with his ninth feature film.

We all thought that he was at his old ways again, when it was announced that Hollywood would be released on the 50th anniversary of Sharon Tate’s death (at the hands of the Manson family), particularly because the film is partially based on her final months alive. What gall does Tarantino have to do this? The film got released a bit earlier (maybe because of its Cannes reception, and as to not compete with other awards season films in August), but it’s still close enough. After seeing Hollywood, I don’t even know where to begin. Never could I imagine that a film of his would shake me to my core, and render me fighting back tears. As a passionate obsessive for ‘60s pop culture, and one who has taken interest in Tate’s legacy, all I can say is thank you, Quentin. If you have not seen the film, it may be difficult to see why I approve of his original release date plans (I will go into greater detail in the spoiler section below), but all I can say is it’s beyond the least selfish idea he has ever put to screen.

Rick Dalton and his stunt double Cliff Booth on the set of Bounty Law, televised.

Before we get into all of that, we need to discuss the actual three interwoven stories. The stories of Dalton and his stunt double (Cliff Booth) are a little more literally connected. Dalton has an alcohol problem, so Booth has assumed duties as his chauffeur and care taker (and not just a stunt double or friend). Booth himself has a tarnished reputation in Hollywood: an accident gone wrong has half of Hollywood claiming he’s innocent, while the other half think he killed his wife intentionally. He is stuck as a stunt double, and one that not everyone even wants to hire because of the urban legend. Meanwhile, Dalton is fighting to save his career, after he is deemed a washout by his agent. Much of the first acts of the film are both characters saving face; Dalton cracks when he is in a private location, though, while Booth never even flinches.

Dalton lives near the Polanski household, and he dreams of one day actually approaching Roman to discuss being in his next feature. Of course, Dalton and Booth are fictitious characters, and are based on the real relationship actor Burt Reynolds had with his own double at the time. Like Basterds does, Hollywood takes an artistic liberty by being its own narrative, despite being based on many real people and events. Many of them pop in and out, including a brief appearance by “Steve McQueen”, an even briefer cameo by “Michelle Phillips”, and other notable faces. This is where Sharon Tate comes into the picture. She barely talks. She mostly floats. Tarantino shoots Margot Robbie as if she were a lingering spirit, or an untouchable jewel. Immediately, you can recognize that he is doing something different, here. Tarantino usually isn’t delicate with his subjects.

Sharon Tate spending an afternoon alone.

Much of the film, like any other Tarantino affair, is all about juxtaposition. You see Dalton have a meltdown because his alcoholism is getting in the way of his acting. You cut to Tate watching herself in a theatre, wide eyed, full of joy, and actually moving in her seat. You can truly sense the spirit within Tate, and how she genuinely loved being a rising star. You compare this to Dalton who is squandering his fortune away, and you get two sides of a coin. Booth is the edge of that coin: a guy that never truly cared about being the full star, but enjoys what he does anyway (and doesn’t want to stop over some stupid rumour).

Of course, we have to now talk about that topic: the Manson family. If you don’t know much about the whole ordeal back in the late ‘60s, Hollywood may just kind of creep up on you like a strange horror film. If you do, each moment is a stepping stone towards the inevitable. You hear certain names. You go to certain places. It slowly, but surely, unfolds. You know it is coming, but you simply cannot do anything to stop it. You cannot travel through time. You cannot prevent this. You can only sit, and watch. You are but only a cinema patron.

Dalton and Booth having a night on the town.

SPOILERS

Tarantino is not a viewer, here. He is a maker. He chose to rewrite history once again. Before, it was a macho plan to cleverly end the Nazi regime with the very artwork they despised. Here, it’s much tamer (well, it’s a Tarantino film, so it’s still extreme). The intentions are much more noble. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is an homage to Sergio Leone, but it’s also an important reminder in this film (hence why the title is only brought up at the end). Tarantino uses his film as a time capsule. He recreates the ‘60s in many ways, to place you there. Now that you’re presently back in time, he will stop what we already know. He stops the infamous Polanski household killings (including Tate and her three guests: Jay Sebring, Wojciech Frykowski, and Abigail Folger).

The inclusion of Dalton and Booth thwarts time. Dalton’s hatred for “hippies” allows him to rage in a drunken stupor towards the family members that are present; this sends one member fleeing with the car. Three are left, and they’re without a getaway vehicle. In a daze, one of them decides to go after Dalton. They follow back to his house and approach him, only to see it’s his double, Booth (Dalton is in the pool out back, blasting music on his headphones). Insanity ensues. Tarantino does not hold back, truly using cinema as a means to get psychotic with the family that killed the last shred of Hollywood innocence the day they took Tate’s life.

Tate, in a different part of Hollywood, enjoying the night in hew own way.

Suddenly, it has happened. A heavenly voice erupts on the intercom. Tate is alive. Time has been changed. Dalton was recognized for his work by Tate, and is invited to come inside. The title appears: Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood. The ellipses are important, here. This is the Hollywood ending. Dalton was a hero, and he had to do his own stunts when Booth couldn’t anymore. He brings back the flame thrower in a blaze of glory. Booth somehow survives being stabbed. Dalton is recognized. Tate is alive, and history is rerouted. This is the Hollywood ending. It can never happen, but Tarantino let it happen, here.

In a way, Hollywood is Tarantino’s most Lynchian film. The fascination with Hollywood (especially during the ‘60s) is important, but it’s also about using cinema as a parallel universe to change our own reality. Like Twin Peaks: The Return does, Hollywood plants a new figure in a familiar time to prevent the loss of life. Like Mulholland Drive, a “dream like state” allows for positivity to overcome the brutalities of humanity. When Tarantino wanted to show Hollywood on the 50th anniversary of Tate’s murder, he wanted to do his best to reintroduce her legacy to new generations, while creating a new now. Some critics are torn by this ending. Perhaps they wanted to see how Tarantino handled the Manson murders. I think this is a bolder ending, and, for once, one we least expected from Tarantino. Decades later, and he can genuinely surprise us still. The shock here is not how offensive he can be (while Hollywood still is quite offensive), but how Tarantino utilizes the film as a metaphysical dimension that went against his usual protocol, and did something pretty gutsy for a mainstream film with biopic elements. It transcends Hollywood from being a grand old time, into being one of the most moving experiences of the year.

END OF SPOILERS

Dalton playing a villain in a television serial.

The way Hollywood is shot — with slow moving crane shots, and nice long takes — is very graceful, compared to the usually quick-cut laden films Tarantino is known for. The drifting between static, music, and advertising is a '60s time capsule that will be more than pleasant to the ears, especially in such a dreamy film like this. Sure, there are fast paced moments, as this is a Tarantino film, but much of the film is Tarantino trying to show us why he wanted to become a filmmaker in the first place. Dalton’s scenes are mostly comprised of him being on set, and we may even forget we’re watching a film about films for a few seconds, as we get sucked into the westerns that Dalton stars in. That is, until he flubs a scene; one of my favourite parts is a complicated dolly movement during a scene, where Dalton screws up and the shot has to be reset, and the dolly moves back to starting position all in one cut (as if we are the camera operator). Hollywood is all about hemming the line between life in the movies, and real life. With the ending it boasts, it’s easy to see why. Again, this is Tarantino honing David Lynch; maybe not intentionally, but it’s there.

It is also secretly his third western. He longed to be a “western director”, and claimed that one needed to have three films of the genre under their belt in order to be considered one. Between the Dalton films blending with what is real and Booth’s excursions, Hollywood is somewhat that third western. It continues to follow western tropes, especially during the moments of great tension. On set, Dalton and his fellow actors experience drawn guns after moments of patience being tested. Off set, a car carrying Manson family members rolls in like the angel of death on horseback. Tarantino still commands films with his ability to create anxiety (as he learned from Leone and other greats). He also bid farewell to westerns by making a mutt of a film that dips its toes in the genre, enough so to warrant the title

I could go on all day about Hollywood. How the Bruce Lee scene left me feeling a bit uneasy at first, only to be reminded that it is a ‘60s projection (and a Hollywood take) in the grand scheme of things (also meant to be the shattering of reality, once Booth gets involved). How the parallels between the three storylines create so many outlooks on the industry Tarantino adores the most. How the film goes above being a tribute to movie making, and becomes one of the most audacious films of the year. It’s too bad it’s Tarantino’s ninth film. I like seeing this softer side of him. As it stands, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is the best film Tarantino has made since Pulp Fiction (and that is saying a hell of a lot), and it is one of the few films helping to end this current decade off with some real firepower.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.