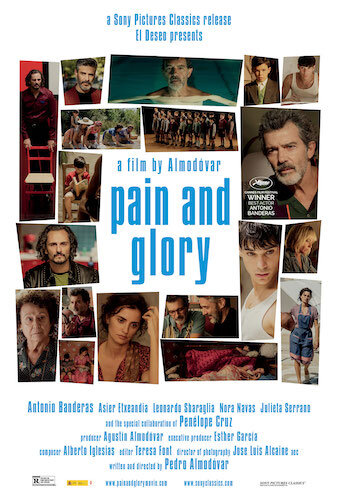

Pain and Glory

Finally. We've witnessed the return of Pedro Almodóvar as Spain's best cinematic export since Luis Buñuel. Things were looking like a bit of a standstill for Almodóvar, whose previous film Julieta was interrupted by the unfortunate Panama Papers scandal. Pedro's brother Agustín Almodóvar assumed full responsibility (he's acted as Pedro's financier and head producer since the '80s), but the damage was done. One of Spain's finest contemporary artists succumbed to a lukewarm reception for an otherwise decent film.

Pedro Almodóvar has always placed his own personal experiences in his films, particularly his affinity for experimental film, his connections with maternal figures, and growing up queer after the reign of Francisco Franco's dictatorship. This time around, he really used his life as the drawing board. Pain and Glory is Almodóvar's 8 1/2, sans the dream sequences. Antonio Banderas (one of Almodóvar's first key actors, who returned this decade to work with the filmmaker again) even dons his friend's quiff hairstyle and facial fuzz. It's all too clear that Pain and Glory is heavily derived from Almodóvar's mental state at the exact moment of the screenplay's conception.

Salvador trying to drown out his physical pains and mental stresses by swimming.

How do we know? Well, Almodóvar used writing to cope after his own back surgery (a major theme in Pain and Glory is the body's betrayals against the host mind in the latter years of one's life). Salvador (Banderas, and the symbolic version of Almodóvar himself) grows up in extreme poverty with his mother. They live in a "cave": a living quarter whitewashed and sculpted by the clay of the earth. Now, not everything Almodóvar places here is identical to his life. However, he did grow up relatively poor. He also had a mother that taught illiterates how to read and write, which is precisely what Salvador is asked to do here.

Everything from Almodóvar's separation and reunion with Banderas, veteran actresses playing maternal figures in his life through his films (Penélope Cruz is literally playing his mother here), and his early works getting restored can all be found here. Salvador has no inspiration to write. I'm guessing Almodóvar was in a similar place. Salvador turns to self destruction as his muse: discovering how to smoke heroin. From what I know, Almodóvar himself did not partake in drug use (especially not of this nature), but he knows all about being fixed to a habit in order to escape (he used cinema). Either way, this is likely meant to be the escalation of Salvador’s struggles to handle his pressing daily irritations, and perhaps his outcome is something Almodóvar feared of himself: actual self sabotage.

A young Salvador and his mother, both embracing their new living conditions.

The result of this semi-autobiographical tale is a richly colourful confessional. While Pain and Glory is not a farewell, it still carries a similar burden of exposing everything that remains in an artist. Almodóvar just turned 70. He's been at this for almost forty years. He's had one hell of a run, with at least one major staple in each decade. The '80s had Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, the '90s welcomed All About My Mother, and the '00s was barely ready for Talk to Her. Pain and Glory is not as strong as these films, or even some other works in his repertoire, but it's safe to call it his best work of the '10s (just in the knick of time).

Pain and Glory finds Almodóvar not trying to push the envelope so much this time. Hey, at his worst, his films are leagues better than the best of many filmmakers (luckily, this is far from his worst. It isn’t even close to being so). We welcome any experiment he's willing to do, especially this late into his career. Having Almodóvar just sit back and focus on who he is -- rather than what unique premise he can spin this time -- is refreshing. With many recognizable cast members (aside from Banderas and Cruz, we have Julietta Serrano, and Cecilia Roth), his personal spillage is warmly handled by those he trusts the most.

Salvador’s adult living space is actually Almodóvar’s own home.

Pain and Glory may not feel as twisty as his usual works, and much of the emotional weight comes from knowing a lot about Almodóvar himself. Seeing this film without context will still ensure that you have some sort of a journey, but many of the statements are those of a filmmaker vicariously living through his players. If you have insight, Pain and Glory is all the more depressing. Despite not blatantly being labeled his final film or anything, this is still a two hour form of an apology: "This is what I have left as a filmmaker." It's not the announcement of tragic news, like David Bowie's Blackstar was. It's more like Ingmar Bergman's Fanny and Alexander: a soul search of self that was more for the filmmaker than anyone else. Bergman went on to continue for years afterward, and I hope Almodóvar is on that same path.

Aside from a few of Almodóvar's diversions (an animated lecture towards the start of the film, an actor's monologue used as a verbal flashback, and a major last minute twist that may open the floodgates), we're staring at all of his insecurities on blast. For us, we get evidence that Almodóvar is far from washed up. For the acclaimed auteur, I hope he gets closure with his finding of himself. Pain and Glory is not as audacious as some of his strongest works (I still can't imagine anyone else on Earth can remotely pull off Talk to Her like he did), but it doesn't have to be.

Pain and Glory finds new worth in the familiar, especially when it comes to signature faces, styles, and natures in Almodóvar’s works.

This is a conversation between a filmmaker and an audience, in the best way he knows how. It's vibrant, quirky, and, as usual, extremely difficult to directly label. Almodóvar honours these complexities (as well as his usual suspects, including a major performance highlight for Antonio Banderas). Life's simply not basic enough to compartmentalize. Pedro Almodóvar is one of the best directors when it comes to capturing the mosaic textures of the real world. It's about time we got to visit his own reality. With enough self prose, and a dash of fiction to keep things interesting, Pain and Glory is performance art to a fault. The best news? This is clearly a sign that we have 2020's Almodóvar coming up, and he's still looking as consistent as ever.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.