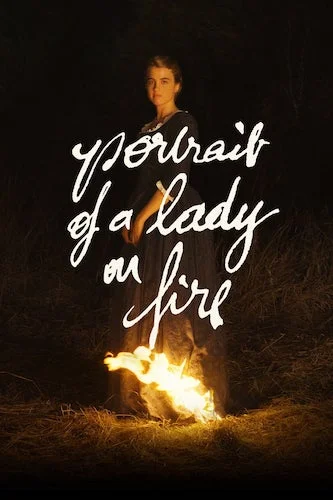

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Editor’s Warning: This is a review of a film shown at the Toronto International Film Festival. There is a chance that this film will not be accessible for a specific period of time, depending on the film’s release date. Be aware that there may be slight spoilers. Proceed at your own discretion.

One word comes to mind when I think of this year's strongest depiction of art: perspective. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is all about vision, and its access to the world, especially through its deceptions and conjurings. Celine Sciamma directs her former partner Adèle Haenel in this period piece drama, almost identically as to how the lead artist Marianne conducts Haenel's character during sessions. This is important, because it shows a sacrificial deconstruction with restraint, in such a riveting way. You never see artist Marianne (played by Noémie Merlant) fully create an image. You only see snippets: the initial sketch, the piecing together of hues, and the finishing touches. These artworks simply come to life. The journey doesn't matter. Their existence is worthy of our focus alone.

In an earlier scene, Marianne tries to play a melody on a harpsichord, but she does not remember how to play the entire song. Sciamma revisits these fragmented passages later on in the film, in a way that will rip your heart to pieces. The previous scene was a work in progress; the latter scene was the symphony. Sometimes, trying to complete life’s unfinished creations is a task that tears away at us more than we anticipated. It fulfils the initial notion, but it uses pieces of us to fill in the gaps. It’s daunting, but necessary for healing.

Marianne towards the start of the film.

Why does all of this matter? Portrait of a Lady on Fire loves to toy with moments, and pieces of a whole. Marianne is instructed to paint Héloïse (Haenel): a young woman set to marry a man despite her reservations. Previous attempts have not gone well, as Héloïse refuses to be painted. Marianne presents herself as a maid, and does her painting behind Héloïse's back. To us, this is a plot.

As the film carries on, feelings begin to blend together like a well crafted artwork. Plot turns into wasted time for the characters. Again, the idea of moments (the brush strokes of a painting, the glances of a loved one) is very important. Like Marianne's paintings, we arrive at a crossroads long before we are ready to make these decisions. This is life, and it simply is not fair. We sit on an isolated shore for lengthy periods of time. Much of the film feels like the space in between, with moves waiting to be made. The film speeds through the moments of progress. When the lead characters are left with their very few options (or lack thereof), we can feel their desperation. There simply wasn't enough time, mostly because we squandered it. The hesitations of panic are real.

A moment of personal bonding.

The beginning of the film -- and its title -- relies on a student in Marianne's art class unearthing a painting of Héloïse with a part of her dress on fire. Marianne can reminisce on any moment. Without giving anything away, it is peculiar that she chooses to pinpoint the absurd. The memory that lacks any true connection. Once the film begins to entrench itself into the great mythological tale of Eurydice and Orpheus, it makes sense. This was the time to turn away. By staring, it was too late. Love blossomed. A nightmare gestated. She should have continued to turn away. Instead, she gazed into the future: both the anticipated, and the unexpected. By now, it is far too late. That flame represents time withering away. That quick glance was enough. It was just enough.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the special kind of film that meanders for a portion of its duration. You suspect it is invested in circumstances, more than it is a tale of prose. You are quickly proven wrong by its finale, where every single event prior gets lunged into your back like a series of knives. Life is cruel with its skewing of time, but it is also sadistic with how it forces your memories to come back. Portrait envelops its memories in a way that renders the entire film bittersweet. We are cursed with reminders, but we also get one last chance to look back, knowing we can't do any more damage this time around. You begin watching Portrait and understanding right away that it is a good film. You finish it knowing it was spectacular.

The realization of squandered time.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a wrenching depiction of a forbidden love hidden in plain sight, like a sketch drowned by acrylics. Sciamma seemingly poured everything she could muster here. The way she wishes to show the world that Adèle Haenel is a hidden gem, is the same way Marianne challenges herself to find that same truth in her paintings of Héloïse. Even the unfinished or destroyed works in Portrait are astounding: a reminder that sometimes a train of moments cannot finish their mission, or that worth can be found in the tragic. Portrait, luckily, is not an unfinished work, nor is it tainted in any way. It is the completed piece, as commissioned by a studio, and used as a message by Sciamma to the world.

Portrait boasts some exceptional photography, amongst other great artistic strengths.

This is an important, authentic take on a queer romance told upfront, with very little to interpret on your own. The empty space in between (the breathtaking cinematography, the use of nature as an ambient score) is what leaps out at you, begging for your own perspectives of it. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the countless times we could have turned away, and we didn't. We are left with a tale of sorrow, which is simultaneously a living painting of a thousand words. It celebrates every single moment, and it will assuredly blow you away.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.