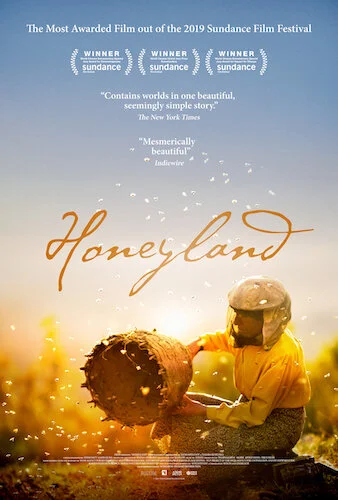

Honeyland

Please excuse our lateness of this review! We are covering every Academy Award nominee of 2020, so we’re cleaning up the films we forgot to critique earlier.

Never before has a single film been nominated for Best Documentary Feature and Best International Film at the Academy Awards (although Pina came extremely close). The blessing Honeyland has received is because of its verité shooting style. There are times you may forget Honeyland is explicitly a documentary at all; it almost feels like a chopped-and-sliced arthouse statement. Quickly you are reminded that this is very real. Not many films can capture authentic pain like the many instances you see Hatidze Muratova exhibiting throughout this beautifully tragic study. As we all know by now, the existence of bees are essential for the many ecosystems across the globe, and their extinction will be the start of the collapse of nature as we know it. Muratova is one of the last beekeepers of her kind (and the apparent final wild beekeeper in all of Europe). You start Honeyland off intrigued by what Muratova does in her every day life, until you quickly remember that this is you staring at the final thread, ready to snap. We need people like Muratova, and Honeyland is there to drill this fact into our heads.

So, we start off with a camera crew following Muratova around, as she cares for her ailing mother, extracts honey from countless combs, and sells her jars of the nectar to survive. She is damn good at her job, and Honeyland puts that truth out in the open quickly. The film is more concerned with what comes afterward. After all, filmmakers Tamara Kotevska, Ljubomir Stefanov and their crew followed Muratova around for three years (all without any severe interruption of her goings on, which is refreshing). There had to have been a reason that this amount of time was enough. Well, Honeyland introduces some inhabiting factors, including migrant beekeepers that have planted themselves nearby. Ecosystems can be very delicate; many locations forbid certain foods at their border to prevent any outside forces from ruining the internal nature. When it comes to bees — a species that is quickly depleting — we learn that it doesn’t take much to affect how they live.

Hatidze Murtova, welcoming the filmmaking crew into her home.

Honeyland is short (an hour and a half on the nose), but it covers much ground. As the practices of the nomadic beekeepers get in the way of Muratova’s operation, you suddenly start to see life around her dissipate. This is a problem for Muratova, whose life depends on this work, but it’s a greater metaphor for what life in a world without bees will seem (even though a few of the creatures in Honeyland die for different reasons). By the end, it’s a snow covered wasteland in northern Macedonia. Muratova seeks out a honey come collective intact, and preserves it for the sake of her job, her life, and humanity. It’s frightening how much depends on something so isolated.

With hundreds of hours of footage recorded, you know painstaking time went into cutting Honeyland down into such a digestible amount of time. This includes the uses of coincidences, staging Honeyland like a narrative feature (perhaps to imply that life is its own art, even by accident). This includes the many efforts to gain a radio signal to listen to music, only to hear the same song (“You are so Beautiful” by Joe Cocker) in drastically different contexts; one scene full of joy, and one full of despair. We endure an entire seasonal cycle in Honeyland, despite the film being filmed over three years; it is presented in a symbolic turning of the four seasons, so we resurrect in the springtime to thrive once more after the darkest of times. Many documentary filmmakers try to force scenarios to prove a point. Clearly, Kotevska and Stefanov know that patience will deliver what you need.

Another day as a beekeeper, in the blazing hot sun in a Macedonian summer.

One running theme is how the adult figures in Honeyland force their children to endure the beestings that they get (including some on the face). Life will constantly hurt you, and you must continue onwards. Like a bee sting, pain is temporary if you’re willing to move on. For Hatidze Muratova, wallowing in misery is not an option, even in the worst moments of her life. Honeybees aren’t disappearing because they want to. They work their entire lives. As a person living in a civilization forced upon us, we have to move on. For Muratova — a dedicated worker that knows the importance of beekeeping for herself and for the entire world — giving up is not an option. Seeing bees die because of selfish business decision making in Honeyland is the roughest metaphor of them all; the squandering of the Earth’s life cycles for easier money is far too real of a statement.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.