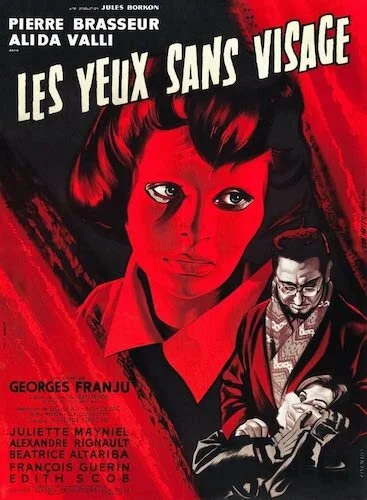

Eyes Without a Face: 31 Days of Horror

For all of October, we will review horror films. Submit your requests here, and you may see your picks selected!

The horror genre is driven by fear: what scares us, or what can scare us. This, in turn, creates a negative connotation with horror tropes, including ugliness, hate, and whatever renders us uncomfortable. What would a horror film with love look like? Well, maybe a satire, or less threatening horror film; either that, or the ruination of love would be fitting. I’m talking about authentic love, where someone makes sacrifices for one they care about. I think the safest way to go about this would be to have this character be misguided about love, as to not remove the dangers that the best horror films contain. Enter Georges Franju: the kind of filmmaker who is daring enough to venture forth towards this kind of writing with a handful of other writers, adapting the text of Jean Redon (who also helped with the screenplay).

This adaptation took place in 1960, no less. Franju saw something in Redon’s Les yeux sans visage — Eyes Without a Face in English — that catered to the kinds of genre tweaking (not quite bending) that the auteur was already becoming acquainted with. As graphic as this story is (and it sure is graphic for a 1960 audience), there is a heart here that is bittersweet. Doctor Génessier means well when he tries to help his daughter Christiane, whose face has been disfigured in a vehicular accident. That’s the love I’m talking about: a father trying to save his child. However, it’s his means that make Eyes Without a Face the horror classic that it is, as he experiments with skin grafting on animals, and kidnaps people in order to use their faces for his project. These are terrible actions, and any normal person can tell you that. When you’re a father dealing with trauma and the hurt of a child, what seems right anymore? Everything in Eyes Without a Face is based on good intentions, and that’s the most horrifying part; Doctor Génessier is inherently disturbed, or was driven off the edge of sanity.

Christiane and her mask help instil a mannequin aura in Eyes Without a Face, which is a purposefully cold film.

Christiane dons a mask in order to hide her scarring, but this only adds to the ultimate goal that Franju had from the very beginning: make a frigid horror film. Eyes Without a Face is so cold in a gothic way, as if it drew inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca, where people just exist in Manderley. In Eyes, we’re trapped in the Génessier mansion, which similarly feels like a privileged labyrinth like the iconic fictitious estate in Rebecca. Every shot is full of angles or shadows. Despite the large exterior, the inside of this structure feels claustrophobic. If anything, parts of these living quarters feel like a prison or an asylum, and we are trapped inside and left to go deranged. Considering the fates of essentially every character — those that live there and those that are led there — we are trapped, without any real ability to leave. German shepherds and other animals are similarly caged or locked away, too. The outside world becomes all but a dream.

The nightmare would then have to be what’s happening in this mansion that’s tucked away from society. Doctor Génessier and his experiments are absolutely gruesome to look at, even for a film that is sixty years old. What is especially disturbing is how the film fixates on at least one surgery, so you fully understand what these procedures look like. Many horror films have victims fall over, act stupid, or commit some other annoyance in order for the villain or event to overtake them, at least for a scare or two. In Eyes Without a Face, there is nothing one can do when they are anesthetized and unconscious, and their surgery just keeps going regardless. It is the ultimate form of helplessness. So, how does Franju shoot this? With the utmost care, as to render this moment beautiful. It’s a strange limbo to be caught in, where the film is equal parts disgusting and gorgeous. It’s the discovery of art in the worst qualities of the human condition. Franju is extremely twisted for this.

The surgery sequence is equal parts disturbing and extraordinary.

All of Eyes Without a Face is this poetic, and the film carries an airiness that you can almost feel. The goosebumps you develop may be from fear, but they can also be attached to the chilliness of the film, as if a literal wind was coursing through your viewing environment. With the reliance on minimalism — including some silence or simplistic imagery — Eyes Without a Face feels delicate. Even though we’re following the doctor and his many misdeeds, it’s as if we’re viewing the events through Christiane’s eyes (the titular eyes without a face), as a quiet observer that sees the horrors of humanity and the brilliance of living at the same time. With a mask on, Christiane can’t really react to anything out right. We can only assume her inner thoughts, until she finally acts out on them in the third act of the film. Otherwise, we’re left to our own devices, curious as to whether or not the film justifies what Doctor Génessier is doing.

The last act feels like a different film of its own, as if Eyes Without a Face has gestated from the mutation caused by sitting idly. It’s the breath that such a film required, and it’s the kind of shift that has made the entire feature timeless. Sure, Eyes Without a Face would already be brilliant if it remained as still as its majority, but knowing that it went darker and exceptionally nuanced when the time was right is what solidifies this vision as one of the great horror classics to ever exist. I’m not sure how much of the film will actually scare modern day viewers, but I can’t imagine anyone finding the film disinteresting, especially with the extra steps that it takes. The further into this unknown territory that the film goes, the more exquisite it gets (yes, even within its brutalities). Many horror films (especially the ones made for horror fans sake) become monotone, as their frights gets spread throughout, or the same ideas as before have to carry out until the end. Not Eyes Without a Face, which takes a leap; it also doesn’t forget the film it is and lose its tone entirely, either.

The ending of Eyes Without a Face is unforgettable, thanks to its dark turns.

Today, Eyes Without a Face has quite the following, including an ‘80s pop hit that circulated the airwaves for a little while (I don’t think Billy Idol’s tune really has that much to do with the film outside of its name and chorus, though). There’s just something about Georges Franju’s opus that sticks with people, as if it were a film conjured up by haunting memories rather than filmed sets and performers. It feels like it’s of another dimension, despite being hyper realistic in some ways (particularly biological examination). A film that frightens you shouldn’t feel this spiritual, and yet this one does. Like many great pieces of art that are difficult to pinpoint, Eyes Without a Face is a singular experience that feels unlike any other film. Morality is tossed out the window. The outside world is unobtainable. Love is driven by torment. Acts of kindness are evil. In one way, Eyes Without a Face completely neglects so much of the horror checklist that many directors swear by, but it is still clearly a film of the same genre, without rewriting too many of the rules. I guess Franju was just able to find horror in new areas, and the main untapped well he discovered was that fear can be found in beauty: physical, poetic, abstract, and spiritual.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.