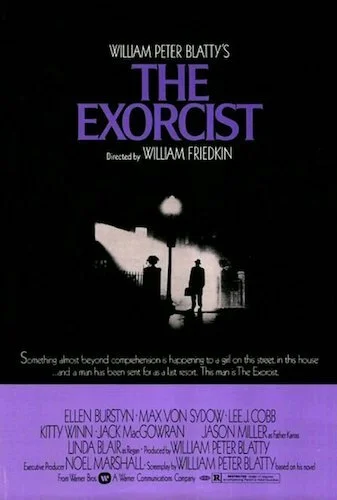

The Exorcist: 31 Days of Horror

For all of October, we will review horror films. Submit your requests here, and you may see your picks selected!

It’s a bit brash of me to say, but it’s rare for a film that’s so ingrained in pop culture to be kind of misunderstood. Allow me to explain myself: those that have seen The Exorcist will likely agree with me with what I am about to say. Because it’s known as the film about the devil possessing Linda Blair (oddly enough the actress’ name, and not the character Regan MacNeil), I feel a lot of the emotional aspect of the film gets lost in translation. For me, The Exorcist is a film about a mother losing a daughter, told in an extremely disturbing way. There’s a lot of ways that mother Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn) loses her child in this film: Regan’s loss of self control (accidental urination being the early sign), mental illness (hence why Regan is taken to psychiatrists), early sexual exploration (the crucifix scene), a renouncing of religion (I don’t need to explain this), and other notable examples. In many ways, Regan moves further and further away from a mother trying to be a sole parent and provider at the same time, and it has become her worst nightmare.

To me, that’s why The Exorcist is such an effective horror film. There’s that familial connection, seeing a loved one vanish underneath a demon, without any sign of hope in sight. All of that devil stuff is secondary. The symbolic depth is prioritized, and it’s something that can land with every single viewer. It’s what adds context and importance to every shocking image, especially for the many conservative audiences that wanted to write this film off for being blasphemous (the film never takes an anti-religious stance, right?). There’s so much going on here that’s poignant and the actual core of the film. So, all of the body possession doesn’t matter, right?

Linda Blair as Regan became a pop culture staple after The Exorcist.

Wrong. Even still, all of the scares are so damn well done, they too hit their mark every single time. Even nearly fifty years later, I dare you to look at all of the special effects and tell me most of them don’t hold up. In horror or any genre, The Exorcist boasts some of the greatest physical effects in cinematic history. Some moments still boggle my mind; I can figure out how Regan’s carotid angiography is done, but it still looks far too real for a film from 1973. Then there’s the upside down spider crawl down the stairs, the levitation, and so many other incredible tricks. It doesn’t matter if they get explained to me; I’ve seen a number of these sequences laid out and discussed in videos. They are all effective, no matter what they were about. The film could have been about fantastical magic, or science fiction abilities. It just happened to be a horror involving demonic possession, so it naturally scares anyone that watches it.

A good portion of the success of the scares — as well as the drama — comes from how William Friedkin and company made this masterpiece. The clever editing lets each cinematic illusion stay real, whilst letting conversations and isolation breathe. The cinematography lets light be overcome by darkness, only for light to leak out at the right times (creating both horrifying and gorgeous visuals). The music, including the use of Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells Part One” (with an exceptional use of contrast) enters your stomach and refuses to leave, lingering inside of you for eternity. That’s something that many horror filmmakers have no concept of: a good horror film has to be a good film first. Friedkin isn’t even a horror director by heart; he just likes to experiment, and it’s clearly evident here. Due to how well made The Exorcist is through and through, every part that’s meant to be scary works perfectly. Imagine someone more inept trying to make this film; you needn’t look far, with those Exorcist sequels (especially The Heretic) in existence.

The iconic split-second image that instils subliminal fear.

The scares are everywhere in every single format, from long gestating dread to jump scares; lest we forget the subliminal imagery used in mere frames, meant to create uneasiness without the viewer knowing exactly why. However, they all stem from the story, which willingly produces horror in all ways at any given time. Because of this, something will terrify you, guaranteed (or at least make you feel uncomfortable). There is something for everyone here. You don’t need to be religious or a parent to feel the impact of The Exorcist, and it’s a major reason why it has become a go-to for any kind of cinephile around the Halloween season (or any curious teenager told about the film, considering these traditions haven’t gone away since I was a teen anyway).

I do recall being bothered by one small piece of the story: why does the MacNeil household have a Ouija board for Regan to play with? Mother MacNeil claims it was just there when they moved in. I used to consider this a lazy piece of storytelling, and it annoyed me for years. After the exploration of many films and over a decade to digest, I have finally found peace with this. Not everything has to be explained fully, and I have discovered some curiosity in this piece of the story; who left the Ouija board, and why? Maybe the previous owner found trouble via talking to the dead as well. Maybe the board carries zero significance with what happens to Regan, and it’s a red herring. Like the devil himself, I began to be driven crazy by this one slice of the film, and it wasn’t even a part that was meant to affect audiences greatly. That’s the power of The Exorcist: a brief moment shrouded in mystery was even strong enough to possess me. I considered it a flaw that chipped away a near-perfect film. I have now claimed it the cherry on top of a flawless horror.

The effects of The Exorcist remain noteworthy.

Of course, for most normal people, other parts of the film are what render them sleepless: Regan’s propulsion vomit, her many disturbing claims, the burning of holy water, and et cetera. Even as a dissector of films, there are things that Friedkin and writer William Peter Blatty have tossed in to make us unsettled as well; feuding pacing of two stories that converge, minimalism versus maximalism, and a villain that just won’t stop claiming protagonists in every single way. As a film alone, it’s a highlight of the 1970’s that marked yet another notable shift towards the New Hollywood era’s zenith. As a horror film, it’s simply one of the greatest of all time. It spits in the face of all of its viewers, tosses us around and abuses us like the victims found in the film. Regan’s possession is our possession.

By the end of it, it’s all over, but we feel as though it will never leave us. Fifty years later, it hasn’t. Not many films can compete with its scares. Certainly only a handful of horror films are as concerned with complete cinematic building as The Exorcist is. It is a staple of horror, of New Hollywood, of cinema and of pop culture. That is the result of filmmaking for the sake of the medium rather than the box office returns of fright junkies; ironically, it’s one of horror’s greatest successes on that front, too (Pazuzu really is unstoppable, huh?).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.