Cinematic Illusions on a Frame-Based Level

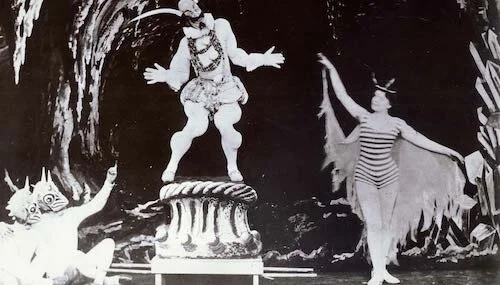

Today’s article is going to be a tiny bit of a film history lesson (barely), and more or less just the raising of awareness for any reader that comes across this piece. Film is full of magic, including special effects. However, I’m more interested in film as a visual illusion. Films are a bunch of images played in succession to create the effect of movement (you can read more about that in our lesson about frame rates here). Within these frames, little tricks can be placed to either create an even crazier effect, or a subliminal image can be placed. On a more basic level, there’s Georges Méliès, who was arguably the grandfather of special effects in films. A magician first, Méliès used the medium as a way to expand the capabilities of the craft. The trick I’ll focus on today is his use of jump cuts to create the appearance of teleportation, creation, and transformation. You can find all of those in the film below.

Of course, we’re going to narrow in on an even tighter level of these kinds of tricks, but it’s important to know where they came from. Méliès didn’t necessarily work on a frame-based level, but he did use the techniques of the moving image to play tricks on your eyes. Readers in 2020 likely know better, and the above short doesn’t really seem all that convincing, but that’s not the point. Méliès wanted to spread joy with magic, so he helped break the medium as a realistic depiction of life (many early films were based on real events that people wanted to see on the big screen), and turned it into the possibilities of anything and everything.

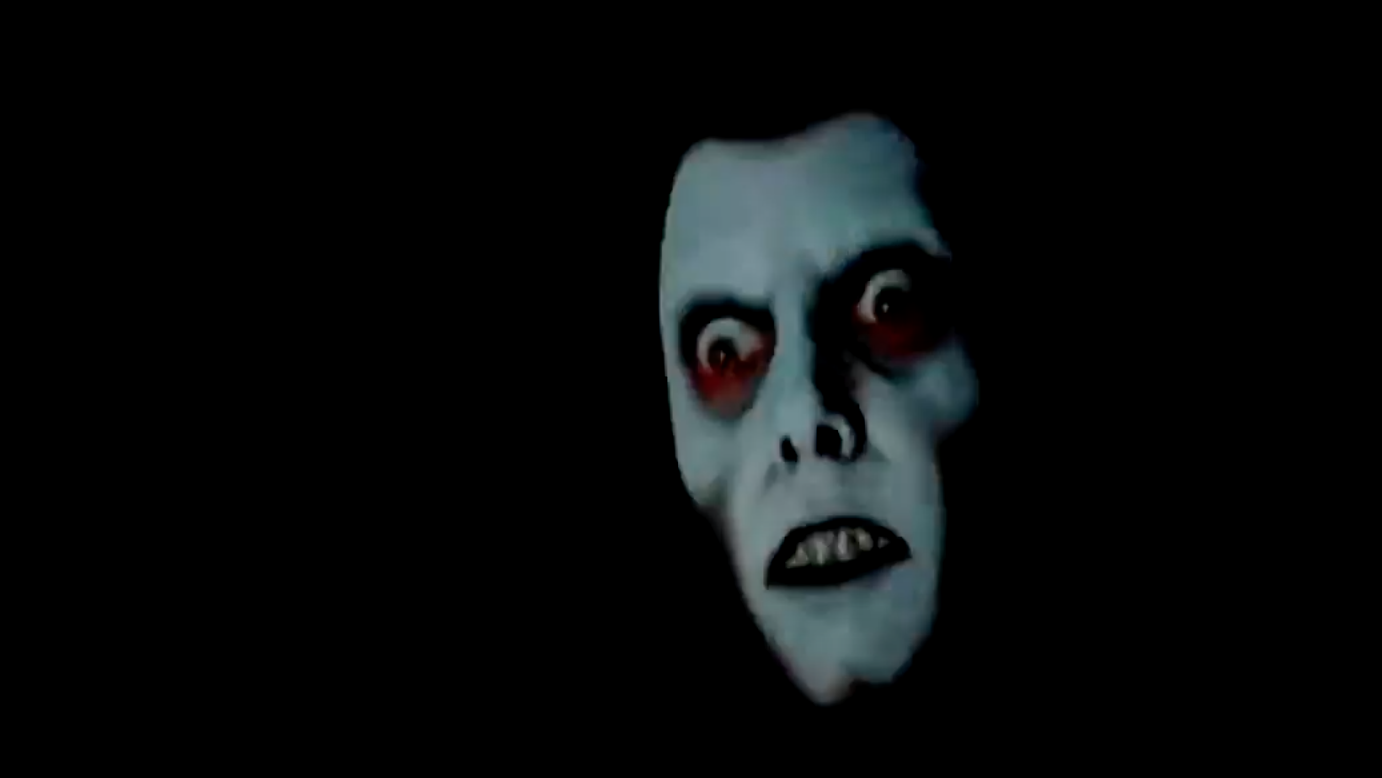

We’re jumping super far ahead into the ‘70s. Film editing is much sleeker. The capabilities of splicing images together is far superior to the ways of early cinema. In The Exorcist, there is an iconic moment where a ghastly face (perhaps of the devil) is shown for split seconds. In theatres back then, you might have felt like you had gone insane, having seen something that wasn’t there. Today, we have long since had the ability to pause and slow down footage, so catching this subliminal image isn’t so difficult. Firstly, here’s the sequence in question (with some rewinding at the end).

Now, in case you missed it (which isn’t likely, considering the thumbnail is of the face I’m talking about), here is the demonic faced used for mere frames.

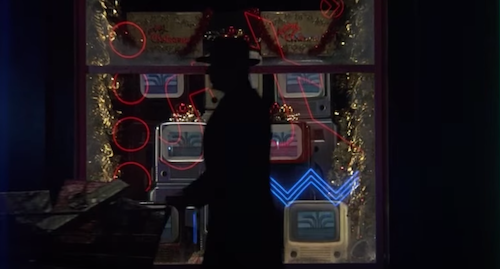

Let’s fast forward to the ‘80s. Animation now exists on a wide level. CGI has started, but is in its primitive stages. Terry Gilliam has released Brazil: his magnum opus. A now-well-known trick happens right in the start of this satirical dystopia, when a bombing explodes an entire man (don’t worry, it’s not as disturbing or gruesome as it sounds). First, let’s watch this charming scene.

Wow. Convincing, right?

What if I told you (those that haven’t heard this commonly discussed piece of trivia) that this effect was achieved by the man being illustrated — frame by frame — by permanent markers on the film itself?

If we break down the effect into individual frames, you can easily see how this effect is fulfilled.

The final frame of actually shot footage of this mysterious person.

The film then “leaps” into the next phase: the explosion. Clearly a completely different shot, and the figure itself leaps a little bit. The destruction begins.

The next frame, the man breaks apart even more.

By this point, the use of permanent markers is extremely obvious, but you’d never notice it when played at regular speed.

The use of markers are even more blatant now.

The final explosion frame involving the figure, being blown to smithereens; ignore the dissolve of the markings, which is likely caused by video playback.

This sequence is actually pulled off on a frame-by-frame level, as it is only possible to create in such a way (especially without the use of CGI back in the mid ‘80s). Terry Gilliam was an animator for Monty Python, so it makes perfect sense that he used film as a series of separate images to create such an illusion.

Now we cut to today (well, somewhat today). Part of the reason why I wanted to make this article is because I came across the revelation below. English singer Zoe Alexander took part in an audition for the British version of The X Factor back in 2012. Her audition went poorly and she has been marred by infamy ever since, often pointed out as the most explosive contestant they have ever had. It almost feels like a no brainer if you watch the audition below.

A few months ago, Alexander went onto her YouTube channel to speak out against the audition on a large scale. She claims that her audition was heavily edited in many incredible ways. These range from placing unrelated footage elsewhere to create a false narrative (a sadly common tactic with reality TV, the media or documentaries), to making it look like she was doing things she simply did not do. You can find her confessional videos here and here (since these videos don’t deal with the editing itself, I’ll focus more on those in this article, but I still want her to be heard, so do check these videos out). This was all apparently sparked by a recent TikTok video about her audition, and viewers were wanting to hear her side of the story (without her being barred by fake news).

There have obviously been videos trying to discredit her claims, particularly her accusations of the audition featuring things that never actually happened. Naturally, videos putting these claims to shame have come out, and a number of them involve actually breaking down the audition to prove that Alexander’s footage was edited beyond recognition. I’ll highlight two of these videos here. The first one by ODOT Clips actually takes one claim — that Alexander didn’t actually throw a microphone out of anger, as was depicted in the audition clip — and shows its individual frames being clearly doctored. ODOT Clips includes other manipulations here — including the playing of a song in a different key to throw Alexander off — but we’re focusing on the frame related trickery.

Additional evidence is shown by channel Annchirisu, who takes apart other parts of the audition. While she doesn’t slow it down to a frame based level, she still points out things that are clearly fulfilled at such a capacity, including poorly edited moments that pausing at the right moment will reveal.

There are other videos about this audition, and I’m sure only more are on their way. My point in bringing this up today is because I just found the whole situation — and others like it — so intriguing, and I had to correlate it with the innocence of how cinema once was. Initially, these kinds of tricks were meant to achieve the impossible in a fun and entertaining way. Now, with this kind of information being discovered, frame-by-frame editing feels like a manipulative tactic. You aren’t in on the fun, seeing a bat transform into a human being, wondering if you saw the face of the devil or not, or analyzing how the crazy opening of a film was achieved. You’re being lied to.

Sure, this X Factor audition is still entertainment, but it’s at the expense of others, and advertised as reality. Think about it: if Georges Méliès was figuring these kinds of techniques out over one hundred years ago (more like one hundred and twenty at this point), how could it not be perfected to the point of undetectability now? Look at how terrible the edits in the Zoe Alexander video are, and remind yourself that you didn’t even notice them when watching the audition at all; these same lazy edits affected Zoe Alexander for many years (we all owe her an apology; I’m personally sorry for believing the footage for years). Unfortunately, like many things, innocent intentions can be used for nefarious intent and spoiled. Be cautious of what you’re watching.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.