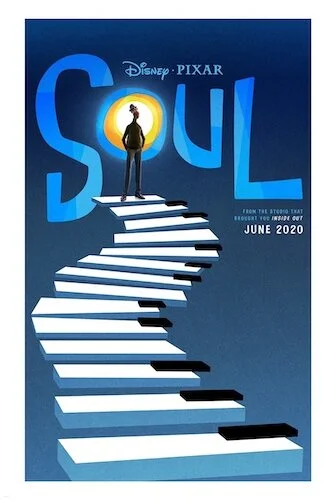

Soul

One of my personal Pixar favourites is Inside Out: Pete Docter’s magnum opus that has permanently changed the way I feel about my emotions forever. Having dealt with depression and anxiety (like many), it was soothing to see an artistic interpretation that tried to explain all of the sensations I just couldn’t figure out. Even if that objective wasn’t reached, Inside Out still is such a creative depiction of the abstract concept of feeling (the chemical reactions in our brains and bodies that we have labeled for our own benefits). So, knowing that the sister film Soul was on its way, I couldn’t help but be excited. So, were we ready for Inside Out 2?

Well, maybe we were, but that’s not what Soul is. There’s still the personification of a personal experience (this time, one’s inspiration, liveliness, and “spark”) within a fictitious world that creates a part of our life experience as if it were a society full of mechanisms and systems. Otherwise, the comparisons stop there. Inside Out focused primarily on the emotions within a young girl’s brain, as if her body was this vessel for the emotions to help control in their own way (identifying experiences through reactions, so the mind can learn). Soul has people functioning as people, but their spirits enter a new concept of what the after world (and “before” world) can be. Docter isn’t really describing how we currently feel (outside of expanding the “zone” we get into when we do what we love, and the spark of life), but rather he is detailing the unknown outside of what we currently can grasp now. Docter himself is a Christian, but he has kept to his mandate of never letting his personal beliefs cloud his pictures, as Soul is a more aesthetically conceptual design of life outside of life.

The universe of Soul is a never ending wonderland of imagination.

Everything outside of life as we know it in Soul is magnificent. The cool colour schemes make for a pleasantly sublime experience, as if we’re not experiencing a world with a pulse, but we’re not entirely dead either. Even the “great beyond” is a dazzling creation, although it signifies the major obstacle of the film; it’s hard not to feel calm if your soul becomes a part of this endlessness that we can’t fully comprehend. Guardians (mostly named “Jerry”) are cubist portraits that shatter our perception of physicality, and almost every single shot with one features a new way that the film goes against our understanding of properties. The creation of new souls that need to figure out their reason to live is an endearing thought, as if we all start our lives with the understanding that we know why we’re here (it’s an anti-existential thought in a film that could have easily revelled in these kinds of philosophical dreads, but Soul opted for the less obvious route instead).

As lovely as this other realm is, it’s how Soul depicts the world we already know that is even more special. Seeing the leaves float in the air, as if you can smell them. Zooming in on textures of furniture. Knowing that pizza grease is oozing off of one’s face as they eat. All of these little details that make life the never ending blessed experience that it is. Soul captures as many as it can. Regardless of what shenanigans are happening at that point, Soul never forgets that its primary objective is to get us to rethink about life itself. Pixar was always fantastic at minutiae in its films; it’s what has branded the breadth of their work with such prestige (I believe a lot of the heart of their films come from the amount of effort: there’s a reason why Luxo Jr. still looks rather fantastic for an ‘80s CGI animation, and it’s in the details). It only makes sense that Pixar’s appreciation of life would be full of the finishing touches that they know of; every drop of sweat or hair blown in the wind is their additional cherry-on-top of each moment.

Life is depicted so brilliantly in Soul.

What makes Soul go above and beyond its already-fantastic premise is its two-step formula. The first ingredient is to deviate from the expected, and Soul is able to do this many times (its climactic moment is an eye-opening realization that all wasn’t how one depicted it, and it’s one of the very few Pixar curveballs that had me trying to figure out where we would go from here; it’s a nice change of pace). The second ingredient is the ability to connect polar opposite sensations. A great example of this is combining the synthetic score of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross with the smooth jazz stylings of bandleader Jon Batiste; in fact, getting Reznor and Ross to make a Disney score in their own authentic way was bold enough. The result is the score of the year: a pairing of two worlds that blend together to tell the unpredictable beauty of life (Batiste) and the permanent warmth of a wholesome death (Reznor and Ross).

All of this surrounds character Joe Gardner, who is simultaneously having the best and worst day of his life; he finally gets a big break with a gig that can get him out of being a music teacher, and his clumsiness leads to him dying minutes into the film. Soul is unique, because it effortlessly shifts its focal points often, in ways I’d argue other animation studios would never dare to. Soon enough, we meet 22: a rebellious soul. We can figure out that the film is really hinged around her, now, and Gardner is more or less a catalyst for her own tale. Then we get the surprise main attraction that I don’t believe was heavily advertised (and, if it was, I missed it), when other studios would have only made the film this niche storyline and called it a day. Not Soul. As long as this thread goes on for (believe me, I wouldn’t dare spoil it), it never feels like the end game of the picture, as we are assured that the film will guide us elsewhere. Of course, we would be right.

Soul skips along its many different avenues, sometimes at the same time, with flying colours.

If it isn’t abundantly clear by now, Soul is a Pixar slam dunk (not by the New York Knicks, though!). Its greatest success is how much care is placed into everything here. It’s the first Pixar film to be lead by an African American character, and there is so much thought put into the character designs to celebrate this. Music is a major component of the film, so there’s not a single false note “played” by the animation, as to create the illusion of an actual performance. Everything “real” or created is fine tuned, as if by a perfectionist model kit collector that had to have everything just so. That perfectionist is Pete Docter, who continues to try and go into unchartered territories by telling stories of the sensations humans still haven’t fully figured out.

This includes fear (to a small extent, with Monsters, Inc.), loss (Up), feelings (Inside Out), and now life itself with Soul. The last piece of evidence that this film was so meticulously crafted is the way it ends: with the film’s title (having not been shown for the rest of the picture, with only a few credits about ten minutes in). The implication — I find — is that Soul was just the prologue to life, whether it’s the lives of anyone in the film, or our own. Once Soul is done, life begins, and that’s the real film that Docter was trying to tell; there’s no better story than your own. Considering Docter gave it his best shot, his version of what life is in Soul is a magnificent effort, through and through.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.