American Remakes: What Do They Get Wrong?

So, Downhill has received scathing reviews. No surprise. The American remake of the successful Swedish dramedy Force Majeure seems to have lost something in translation. In fact, you can argue that this is exactly why most American remakes of great foreign works simply fall flat. One of the rare exceptions is Martin Scorsese’s The Departed (a remake of the Hong Kong Infernal Affairs), and part of that can be attributed to two different reasons: 1) Scorsese knows cinema inside and out, and could make the adjustments from Hong Kong to Boston, and 2) parts of The Departed are shot-for-shot nearly identical (where it counts). Otherwise, how many Hollywood takes on foreign works have been noteworthy, or even satisfactory? Not many.

Again, much is lost in translation. I’m bringing up this discussion today because of Downhill’s backlash and the going-forward of the Parasite HBO miniseries (although American remakes are always a problem that never seem to stop). Before I continue, I may as well bring up an example so you can see what I mean. In Parasite, Kim Ki-jeong (who goes by “Jessica”) has become a viral sensation for what is known as the “Jessica Jingle”: the mnemonic song used for her to remember her false identity while going into the Park household. For the rest of the world, it was a cute ten second blip that was clever, and used to ease a bit of the upcoming tension. For South Koreans, it was a reference to the anthem “Dokdo is our Land” by Jeong Kwang-tae , and thus a major layer of subtext could be applied.

The easy solution — if HBO’s Parasite will mirror the film and not be an offshoot — is to just find an English language song of a similar nature to slap into this moment so it sticks properly. That’s kind of how it all begins to fall apart. Films are made to tell stories or display art in varying different ways. Rarely is a film made with the intention of being remade. I highly doubt Bong Joon-ho crafted Parasite thinking “Yes! Let’s turn this into an American production ASAP”. This is especially true since he has dabbled in English language works before (Snowpiercer and Okja). Joon-ho speaks about the poverty and classes in South Korea first and foremost. The universal message just happens to resonate more than intended. Often times, filmmakers are providing their own perspectives. Asghar Farhadi wrote and directed A Separation after Iran’s voting crisis, so obviously the context here was highly relatable to people that had experienced it first hand: we understand the divide between this married couple, because of how torn Iran was during this time (and A Separation doesn’t need to harp on this point for long).

By trying to transition a film into a different context, producers and studios begin to miss the point of these original works. Instead of telling our own tales from our perspectives, we’re trying to cram a square into a round hole. A Separation was told from this perspective. How can we make this American now? This should be the cut off point, but it rarely ever sets studios back from embarrassing themselves. In the case of Downhill, a marriage on the brink of finality is clearly something all nations can understand in varying degrees, but it’s the tonality of Force Majeure that is lost. Director Ruben Östlund is known for his satirical lenses on what we put on pedestals (marriage here, art in The Square). Do Nat Faxon and Jim Rash play the satirical card very well? Not quite, although they are great at making dramedies with certain levels of introspective analysis. That doesn’t mean this works in Downhill, especially since the original intention was drastically different.

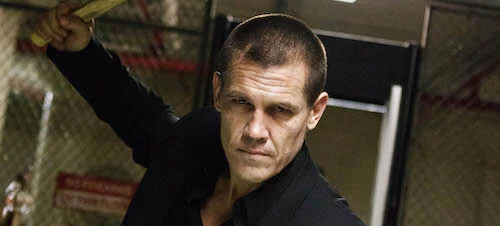

Spike Lee’s Oldboy.

On cultural and stylistic levels, remakes like these aren’t the best decisions, because reinterpretations of great works usually don’t come out better (or even on par). So, why bother? Spike Lee is a fantastic filmmaker who pressed his luck by remaking Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, and we all know how that turned out. However, you can tell that Lee wasn’t trying to cash in a cheque, but wanted to celebrate world cinema in his own way. It just didn’t work out. We’d have to look way back for some additional homages that winded up better than the usual fare we get now. I’m talking A Fistful of Dollars being a Western take on Yojimbo, where a complete overhaul of the story had to be done (and, even though we got The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly out of this, is Fistful actually better than Yojimbo?). I’d even go as far as to say that The Magnificent Seven, while good, is nowhere near a Seven Samurai. So, even the better examples of English language remakes don’t hold candles to their original versions.

Then there’s all of the minutiae. The jokes and situations that work better in original contexts and not when translated. The importance of setting. The personal input by a filmmaker that a fan won’t be putting into their remake, no matter how much they try. Hollywood can barely take control of the remakes of their own works (see Psycho, Carrie, even the newer Magnificent Seven, and et cetera, et cetera, et cetera). I understand that Bong Joon-ho is working on this HBO continuation of Parasite, so at least there is that. Why did all of these companies and studios zip towards him after Parasite, though? Just because of Parasite’s success? Don’t they know he’s been telling the same messages in different stories since the start? Isn’t it abundantly clear that this is for a buck (not for Joon-ho, but from the many studios that approached him)?

This rarely works, because the directives are so starkly different than how the original films are made. Look at Downhill. Force Majeure was made with love, to tell a crisis in a hysterical fashion. Downhill took six years to sanitize the film and warm it up in a microwave for American audiences. Outside of the obvious business people that want to make bucks, most people join the film industry out of the love of cinema. If you love these films, wouldn’t the right thing to do be to leave them alone, as is? In the rarest of cases, where someone knows how to actually approach a remake, it’s apparent that most of these instances are just to make bank, and it’s only doing a disservice to the original works made out of something to say.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.