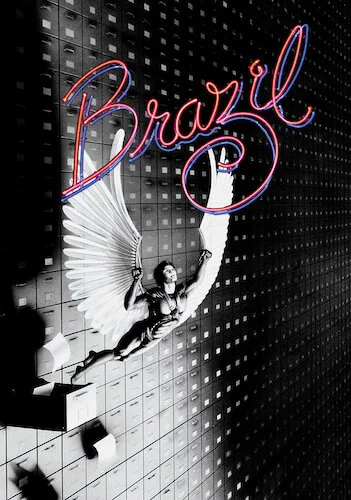

Brazil: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For February 20th, we are going to have a look at Brazil.

Never before, or since, has Terry Gilliam perfected his take on the disgusting now (through the lens of the chaotic “future”) than his finest hour Brazil. It’s as if he read the works of George Orwell (obviously 1984), paced around his living room, and said “hang on a minute. I have a vision here.”, and proceeded to slam the entire story out in one sitting, with a brain cluttered with bureaucratic distastes and apocalyptic fear. Brazil is incredibly Orwellian, but in a satirical sense. It’s as if we didn’t listen for the decades since the late author gave us his warnings, and Gilliam is here to rub our faces in the dirt. Oddly enough, Brazil was still meant to feel like its own cautionary tale, maybe insisting that there is still maybe a tiny bit of time left for us to save ourselves.

Nope. It is 2020, and Brazil, like 1984, rings more true now than ever before. We are all buried in paperwork, which strips even the most demeaning careers of whatever dignity they had left. Our attempts to fix our own appliances (as to save money) nullifies warranties, and so we are screwed financially either way. Our necessity to look a certain way withers us away underneath self work that we will never be completely content with. Brazil is named not after the destination, but the song lead character Sam Lowry literally dreams about: a destiny he will never ever achieve. We all have that shred of hope. Even the most disillusioned of us (like Lowry). Gilliam is here to poke fun at it, and stomp it into the ground. Brazil is meant to be a reality check in the most unconventional way possible: a hyper fantasy.

The congested government workplace Sam Lowry is stuck in.

Lowry is gleefully stuck in a dead end job, but is forced into promotion by his socialite mother. When he does wish to move into a new department, it becomes a painful process. This is life. Our comfort is never guaranteed, and our pursuit of evolution is usually shot down by outside forces. This push-and-pull is found in every single character: bosses with control problems, servicemen that turn towards “rebellion” in order to fix appliances and ducts properly, and the poorest citizens that don’t have a chance in hell of achieving anything here. Even our dreams fall to pieces, as is seen in the reoccurring subplot that takes place entirely in Lowry’s mind. He is a soaring knight, in charge of his own fate (but not for long).

The reality is much more grim. Everything is grey, dusty, and cold. The entire film is shot like a New Yorker cartoon, or like a Jacques Tati cinematographical comedy. There are so many small details that either hit you right away, or creep up on you in your mind. Brazil is cluttered, but it all makes sense, like a fragmented mind. Everything you see in Lowry’s world is smushed together, but his fantasies feel much more open at first; he is literally in the clouds. Once his two worlds collide, the obvious understanding is that his dreams are being polluted by his awake state. The undermined facet here is seeing just how much of his real life is actually a part of his day dream. I’m convinced that certain characters flat out never even existed (who or why I shall not say, as to not spoil this brilliant film).

Ida Lowry undergoing her usual cosmetic practices, including literal face stretching.

The film would have remained in Lowry’s day-to-day nightmare if it wasn’t for him wanting to chase his vision: the girl of his literal dreams (Jill Layton). Well, there’s also the Tuttle-Buttle mix up, which costs the Buttle family their father around Christmas time (as he is detained for crimes he didn’t commit). The world in Brazil is hell bent on paperwork (the document said “Buttle” so it must be correct), but not in any other forms of evidence. We are all slaves to ink on paper, whether it be money (Gilliam loves toying with various forms of debts in Brazil), contracts, or just simple paperwork. Being arrested may affect your credit rating. You get receipts when your loved one is arrested. It’s all beyond silly, but it’s not that far off from the truth by any means.

It’s also safe to say that most of the people in Brazil are inept mentally, probably because they live in a society that despises their existence, outside of how they can benefit their city. Most employees have no idea how to operate within their own jobs (desk pigeons unsure of how to start up a computer, handymen missing out on the proper paperwork, et cetera), but that’s possibly because they (like Lowry) are on another planet deep down. We’re all wishing for our escape from our mundane, suffocating lives. We sometimes wish too hard, to the point that we are satisfied with our depictions, and not our chase for the actual future. We see Lowry’s ambitions on a literal level. Must we assume other characters are stupid, if we can’t see their own daydreams? Either way, you can’t trust anyone in Brazil, either because of their two faced ways, or they are simply terrible at their jobs. A few characters are good, but even then, you can’t trust that they even exist.

Sam Lowry being promoted into an even more intense work environment.

When a society is so unloving, you find joy within, and Brazil is that curse turned into a blessing. When “big brother” is forever watching your every move and outwardly spoke thought, it is your inner reflection that becomes a paradise. That makes the outside world all the more insane. It’s a rare time where Gilliam’s overuse of fish eyed lenses, obscure angles, and extreme close ups works without feeling overly gimmicky, because your eyes straining to make sense of your surroundings is a perfect analogy for this kind of hectic world. Then there are the obnoxious Foley sounds, which either sound a bit out of place (the fly at the start being swatted), or simply unnatural (why would a microphone being covered make a sharp noise?). It adds to this already alien world, and makes you feel disoriented as well (especially those shrill, echoed voices that pop in and out of scenes).

As an obvious member of the Monty Python team, Gilliam has a keen sense on parody, and Brazil is the most he has been able to say whilst still remaining funny. As bleak and shockingly dark as Brazil can get, it is also painfully funny. This includes the skewering of its characters (the workers blaming the metric system on their own idiocies), the puns (“This is my receipt for your receipt”), the slapstick visual gags (Lowry’s “trust me” sign is borderline Looney Tunes), and even the extreme (the singing greeter that shrieks her way into Lowry’s home with her message). There is always something comical going on in Brazil, either in an intentionally funny sense, or in a tragic sense (some of the coincidental twists, or pathetic turns). It’s all a satire, and all of it is amusing even in a pathetic way.

Jill Layton dodging Sam Lowry while trying to work.

As fun as Brazil is, it is bravely vicious, even to the point of being disturbing. The imagery that Gillian has concocted is free to turn in on itself, mutate, and crawl back out as a new plague. Repetition is also part of Brazil’s game plan, whether it’s the conditioning of oddities, or the torture of the unsettling. Whichever effect happens on you for any of the images is entirely dependant on yourself. If the baby faces don’t do it, maybe the gangling pipes will. Either way, Brazil is creepy, despite all of the fashionable moments here (I’m thinking the aristocratic forums, although littered with abandoned parts and dirt, are still stunning to look at). The climactic final half hour is purely dismal, even though it is meant to feel hopeful (the lighter moments are still unnerving).

A complete attack on all of your senses, Brazil is as loud as can be intentionally. While Gilliam mocks the world we live in and those that put us there, he aims to bang his message over your head again and again. AVOID THIS. DON’T BE BLIND. YOU ARE ALWAYS IN THEIR CONTROL. FIND YOUR INTERNAL HAPPINESS. Whatever you can do to follow Gilliam’s word, just don’t end up like any of the finer people in Brazil, who were taken advantage of by the system they put faith into (or simply ignored, and thought that would be enough). The best way to communicate can be through comedy when done right, and thus Gilliam abided. Whether this is a living funny papers section or a breathing Rorschach test, Brazil will make you feel something. Maybe nausea. Maybe shivers. Maybe even uncontrollable laughter.

Lowry soaring through his dream.

In short, Brazil was killed upon release by Universal executive Sid Sheinberg, who demanded massive cuts to the film, including a starkly different ending (it’s amazing what a difference one scene can make). A film about the disapproval of the removal of freedom of speech had its speech revoked. It was turned into an ‘80s romantic fantasy something or other. This is now called the “Love Conquers All” cut, and it’s an entire hour shorter than the final cut Gilliam has sworn by. In 2020, you can make the choice of which of the numerous cuts you are willing to watch. It’s still controlled by the distributors giving us these choices, but it’s much more freeing than being forced a butchered edition.

Besides, that’s not the point. It’s 2020, and we’re still seeing filmmakers being denied their final cuts, publications relying on clickbait, and non powerful people being silenced. Instead of paper work, we have to read through terms and conditions, shuffle through many electronic documents, and fill out many templates. Our devices literally have cameras and microphones on them, accessible at any time. Application filters make us question how we look on an hourly basis. Don’t even get me started on politics: anywhere, by the way. Brazil is very much now. Just made to be more over-the-top. We’ve got our headphones so we can drown out the world with the literal songs of our choosing, whether it be “Aquarela do Brasil” or something else.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.