Growing Up a Cinephile: Write, Camera, Action!

Every once in a while, our writers will promote a film, novel, album, or any other medium or form of entertainment that introduced them into cinema earlier on life. Here is such an example.

For me, one of the earliest introductions to the world of filmmaking was the now-forgotten-about edutainment game by Brøderbund software. Write, Camera, Action! was an immensely clever education platform for children; the mid ‘90s game version of hiding vegetables in meat. The premise is very basic: finish an incomplete film. Unfortunately, this was the ‘90s after all, so there was only ever one film you could work on (you can name it whatever you want, though). It’s basically a very loose spoof of The Maltese Falcon, but instead of a bird statue, you’re looking for a missing cat named Malcom (so the “Maltese Malcolm”, I suppose). What did you have to finish? Parts of the screenplay, the ADR (additional dialogue reads), and all of the production work in a business sense.

For a kids game, Write, Camera, Action! was clearly made by cinephiles, and revisiting this learning journey as an adult made me appreciate the smaller details so much more. I’m even more convinced that this is one of the places my love of films all started, particularly because of the small trinkets and actions that made me feel solely responsible for the fate of one “film”. So, I decided to give Write, Camera, Action! a spin as a thirty year old, well past the game’s expiration date (and its age limit, as well), and reminisce on the many hours I spent creating new accounts, and wiping my dad’s memory off of his laptop with the amount of “films” I made. In order to do so, I had to create an illusionary operation system on my own computer (basically a computer within a computer); there are a number of customizable emulators you can use (I used Basilisk II for the Mac). Then, I found an old copy of the game, and booted away.

I was greeted with my first-ever sense of film noir: a detective looking for clues, amidst permanent nothingness. The cat seems a bit too friendly for the genre, though, but everything else was the start of something great for me. Deep down, I connected with films noir (and especially neo noir) right away when I started diving into cinematic history, and I only put two-and-two together a few years ago. It was because of this game. This was my first exposure to the conventions of a film style that has dominated Hollywood for nearly a century at this point.

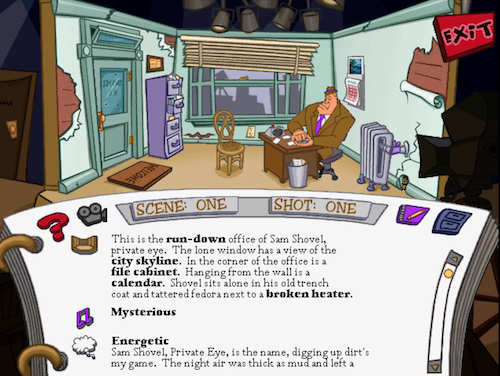

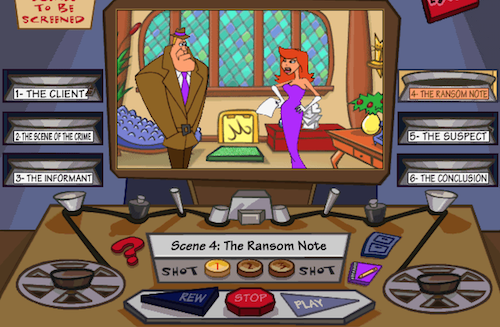

So, the game starts, I make an account, and I am told I need to help finish a film that the previous filmmaker abandoned. The game doesn’t go into what politics or personal reasons have halted this film and rendered it directionless, possibly because this is a children’s game, and no kid needs to know about the stupidities of adults anytime soon. So, you start fixing the film right away. It’s very short: six scenes long, four sets only, and only a handful of characters (all with alliteration in mind: detective Sam Shovel, femme fatale Fann Fatale [heh], antagonist Herbert Howell, and more). You begin to realize how you have to fix the film: most of it starts with the screenplay.

Those bold words are all choices I selected. You have three options for each, and you can change the look of the set, the mood of the score, the delivery of dialogue and more. The choices are a bit limited, as they are all based on three genres: straight up drama, a silly comedy, or a ghastly horror. Of course, none of these options go too far, because — need I remind you — this is a children’s game. The idea is to encourage children to realize the difference in afflictions placed on certain words, understanding specific adjectives, and more. However, Brøderbund went the extra mile by teaching the importance of descriptive screenwriting as well. As a child, I began to lean why I wanted the set to look run down, as opposed to bright and colourful. I was taught at around seven years old that even the objects in a scene can convey meaning of the utmost importance when utilized properly.

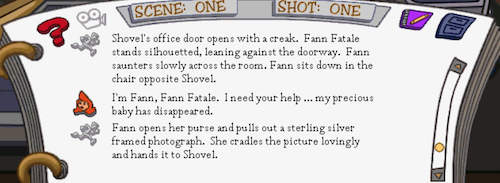

You can take the long route and have the performers “act” all of your decisions you pick, to see how each choice changes the scene. The film acts accordingly. If everything else is serious, but you make the main detective do a sillier action, the Foley sounds attached to his action will sound goofier (steps being replaced with the squashing of tomatoes, for instance). This is all the early point of the game, though. It does take the longest to get through each and every scene, shaping each moment just right. Most of these decisions are subjective, but a few choices actually change the outcome of the film’s narrative. You can make the character Fann Fatale the literal femme fatale who is the “twist” villain, the main antagonist actually be — well — the main antagonist, or create a surprise for the ages and have your secretary be the mastermind behind this entire scheme. Not many choices affect the outcomes, but you become attentive of what your decisions can do.

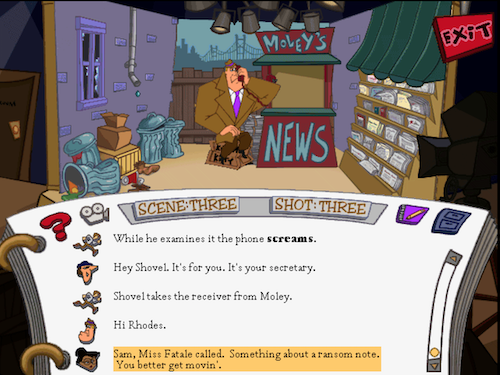

Here, I picked the clue attached to the main detective’s secretary, thus planting the plot seed that this character is guilty from this early on in the film.

The film progresses no matter what choice you make, but it will change the progression of the film. Again, the bolded words are my choices. Everything else is set in stone. However, think about the strengthening of the understanding of a screenplay that a child gets with the above image. If I made the secretary a good character, her line about the ransom note is a positive lead towards finding the real criminal. Since I didn’t, the secretary’s warning is actually an undercover threat disguised as help. These are connotations being introduced to kids. It’s actually incredibly clever.

Enough of the on-set part, since you now have the idea. Once you “shoot” your film, you have to go through every other step in getting this film made. Let’s see the other locations featured in the game.

The backlot is where all of the on-set action takes place, so let’s skip that. The limousine in front is only available once you have finished your film, so you can see the entire finished product without any hassles. “Tours” is just the help button in case you forgot what everything is, I believe. You can check out the box office result on the “Top Ten” board. If your film didn’t do very well, it may have had poorer decisions put into it, or maybe there wasn’t enough publicity surrounding the film. Retry your methods, and watch the film again, and hope to reach the number one spot. I only reached third best this play through, and can’t be bothered to see what I did wrong this time (younger me would be so unimpressed).

The audio studio is actually the most fun part of the game, especially when you’re a hyperactive child discovering new technologies for the first time. It’s essentially the additional-dialogue-read or dubbing portion of the game. If you have a working microphone, you can read over the screenplay to put your own voice into the film. Of course, what kid will do just that? Luckily, I was super young, and not at the “I’m an edgy ten year old” phase, so everything I said was innocent. I remember making the characters talk about stupid things, like my teddy bear friends or the new Star Wars film coming out in my lifetime (little did I know it would be The Phantom Menace). On an emulator, this function sadly didn’t work. Then again, I’m also thirty.

The head office is where you have to do all of the publicity for your film. That means send out headshots, memos, newspaper articles, film quotes, factoids and more. You actually have to type these things out! As a lazy child, I just typed in the following: savtdaustdvaskudt asudvasitdf asdksatd iatyfewqvuas tdwq76ef uastdvktasfe, and et cetera. As an adult, I’d like to think I have a bit more flair. As educational as this portion is, you can still bypass it with good old fashioned keyboard slamming. I can imagine a newer rendition of this game would demand actual words being typed out, though. It’s the least fun part of the game, but not everyone is born to be a producer, I suppose.

Next door is the screening room, which is a little repetitive in nature, but still fun to a degree. You just watch your reels of film played back. Literally, whatever you saved on set will be here. The bad thing is you have to watch these playbacks in order to complete your entire film. However, what makes this part worthwhile is all of the stuff you missed while on set that you can now see in the refined footage.

Firstly, as an adult that has studied filmmaking, editing, and preservation at a university level, seeing this editing table made me shout with glee. The attention to detail in this game for kids is kind of outstanding. What seven year old would really care about this kind of thing? This hard work was clearly for the cinephile parents that bought their children this game, and sat with them to help them learn. This was their reward.

Anyway, back to what I was saying earlier. Here is the screenplay now outside of the set (in any of the other modes). You can’t change anything here now, unless you go back on set to “reshoot” the scene.

So, in this playback mode, you finally get to watch your film with actual cuts, the music put in by the composer (after the set footage), and other minor details that you couldn’t see earlier (it’s, yet again, some particular attention to detail, that renders this game incredibly accurate for a child that’s new to all of this).

Instead of one static shot, we have actual cuts between focal points, and with the background adjusting for perspective to boot! It’s hardly revolutionary, but it’s the kind of change up that even a seven year old me picked up on right away.

You wrap up your screening process, promote the heck out of your beloved creation, and head to the threatre. If only a few people show up, you did something wrong. If there’s a sold out house, expect to be at the top of the box office (and thus you have seemingly won the game). That’s it. There is no definitive end. You can replay this as many times as you want. As a kid, I did just that. I can’t even imagine how many hours were spent with Write, Camera, Action!. And here I was being educated without even realizing it.

I don’t know if games like this even exist anymore (film based edutainment games, not just edutainment games), but I would like to think that they do. I didn’t even know how much a game like this would have affected me in the long run, and yet it did. Years later, when I started watching more and more films, I suppose Write, Camera, Action! gave me a bit of a head start, as stupid as that sounds. Being able to play it (despite all of the technical issues: the game kept crashing while I tried to watch footage of my film) was a trip down memory lane that I truly appreciate. I can’t wait to keep revisiting various events, objects, or media that turned me into the cinephile that I am today. This is only the beginning.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.