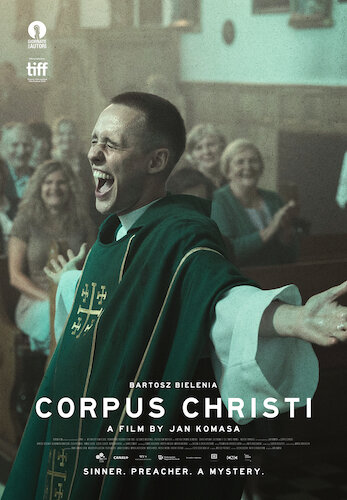

Corpus Christi

What is faith in general? Is it the same answer that we apply to ourselves, if we even believe in anything at all? Jan Komasa dares to describe both questions with countless answers in his latest drama Corpus Christi: the transition of a juvenile convict to a championed small town priest. Komasa is Polish, and his homeland is mostly comprised of Catholics (over ninety percent of Poland’s population practice this form of Christianity). It wouldn’t be the first time that the young auteur dared to ask the tough questions (see his previous works Warsaw 44 and Suicide Room). What makes Corpus Christi special in its rhetorical debates is how the film isn’t anti religious by any means (including lead character Daniel). There is a strong belief here, but life sometimes can make a straight answer as to how this belief works incredibly murky.

Daniel — played by a completely-committed Bartosz Bielenia — has just been granted a second life after serving time. His mentor (Father Tomasz) acknowledges Daniel’s commitment to helping his own services, but admits that Daniel will be unable to hold his own sermons outside of these prison walls. As Daniel battles between his two addictions (substance abuse, and religion to combat his drug use), he finds himself trying to let God overtake the battle. He winds up in a church, and has his priest uniform with him. He’s avoiding his work at a sawmill, and uses this opportunity to start fresh for good. He abandons his post, and declares himself a functioning priest for a small town that could use the extra healing in the aftermath of a traumatic crisis.

Daniel channeling his inner faith, as he holds on to his new life.

Corpus Christi allows every character to have their own faults, so the spotlight isn’t always on Daniel. In fact, you may even forget that he was guilty of anything during the second quarter of the film (outside of his questionable, but noble, amateur methods of conducting masses). Even the vicar he has overtaken has his own demons. However, Daniel is the only major character here blatantly labelled as a criminal by a justice system, so his past hangs over his head like a noose waiting to be tightened. Corpus Christi takes its time allowing Daniel to get comfortable in this parish, and amongst the community. He establishes relationships (professional and romantic). He gets more comfortable with the whole priesthood thing. This may not be so bad after all.

Let’s not forget that this is a Komasa film. The second half of Corpus Christi is devoted towards the notion of guilt, and how forgiveness by some does not equate to absolution by all. This is where the film’s moral debacles really come into play. Should Daniel be reprimanded for something he already served time for, especially since he is fighting to become a better person? A lot of these questions surround Daniel’s outsider perspective on the incident that sent this town into a tailspin (of which I won’t spoil for you). He continues to approach this scenario in a way Jesus Christ may have (he refers to God often, even simply by gazing upon his crucifix), and his ways aren’t necessarily approved. So, who is right? This “priest” that means to act underneath his faith? The town that has attended mass every week, but are all in agreement when it comes to this one tragic event? Daniel’s past that comes back to haunt him?

Driven by passion more than practice, Daniel commands a small town.

Near the start of Corpus Christi, Daniel’s first post-juvenile-hall action is to get smashed at a rave. With the booming house music (of which Daniel is privy to), you can find associations between faith and letting loose. Daniel finds these same connections (as well as within practices he experienced while detained), and creates his priesthood identity out of the basis of cult (even if it’s just for himself, and not for the rest of the town). As Corpus Christi continues, he shifts into more of a traditional Father; conveniently, this transition happens while his world around him begins to collapse. Jan Komasa handles this tricky representation with ease (but also just enough grit to keep things interesting). We spend so much time seeing Daniel amalgamate himself within the church, that the sudden conclusion feels like Daniel’s ultimate test. He’s spent so much time proving himself to his religion. What happens now, when we don’t know where to turn next? Will religion get us where we need to go, even with a mark that we simply cannot shake off?

The Academy Awards love to select at least one film that the general public won’t be able to see for themselves until the tail end of the season, or even after the ceremony has taken place. This is omitting the possibility that you may have had a chance to see these films during a film festival, perchance. This year’s torch bearer is Corpus Christi, and I can’t recommend this film enough to extend your Oscars’ season viewings. Its handling of its faith-based subject matters is neutral enough that you don’t have to be religious to understand the power of the narrative by any stretch. Knowing the inner workings of passion versus addiction is simply enough. Every scene is shot with muddy greens and gloomy blues, as if life has been abstracted out of every crevice in Poland. Corpus Christi is about finding light (even if it is blinding) to finally move out of a dark corridor, and just doing your best to not mind the shadows that follow (because they will indeed follow). The credits cut their way into the final scene, in pitch darkness. It’s 2020. Abrupt anguish is what we eat for breakfast nowadays. We just have to move on.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.