Breathless: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For March 16th, we are going to have a look at Breathless.

One of my all time favourite Criterion Collection releases in a physical form is the Jean-Luc Godard masterpiece Breathless. The front cover is just the title of the film and Godard’s name. The spine is an image of the stars Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg in character. Those who haven’t seen the film may not think too much of this presentation. For me, this is breaking the rules of home release presentation in exactly the kinds of ways that the film itself strayed as far away from conventional filmmaking as possible. It’s as if the spine’s label became the front cover, and the photograph intended for the cover is now on the spine. It’s subtly clever, and so indicative of what this film represents.

Breathless deviated away from standard filmmaking practices so viciously (and, at times, poetically), that it basically became a new language for how film can be represented. Like Dziga Vertov before him and Sergei Parajanov after him, Godard sought for a new way to converse using celluloid. The very first frame of the film (excluding the title) is a shot of a cartoon pinup on a magazine, with lead character Michel (Belmondo) pondering on whether or not he is an asshole. For 1960, that’s one hell of a way to start things off. It takes a real brainiac of a field to be able to dismantle it properly; otherwise, you just have someone who doesn’t know what they’re doing not understanding why these are the rules (or even what the rules are). Someone like Godard is purposefully going against the grain in ways that add something new to what you’re seeing.

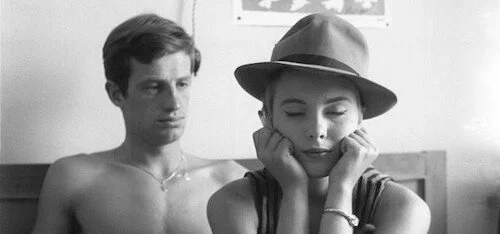

Michel and Patricia spending time together.

Godard was a part of Cahiers du Cinéma: the influential film journal that also spawned the careers of numerous other important French filmmakers (and has remained potent to this day, excluding the recent purchasing of the company which resulted in a majority of the writers walking out, but that’s a discussion for another day). On that topic, I want to be a little defiant myself; it’s only natural in a review about Breathless. This is seen as Godard’s baby, and one of the earliest works of the French New Wave movement (alongside La Pointe Courte, The 400 Blows, and Hiroshima mon amour). What’s often left out is the screenplay being written by other Cahiers alumni and important French New Wave figures, particularly François Truffaut (Claude Chabrol also had a hand in helping write the script). I’d argue that their words are just as important to the story, particularly because Truffaut was a much more graceful filmmaker than Godard; his films felt more emotional than thought provoking, in a sense.

It’s as if Godard took the existential whirlwind of Truffaut’s script and hacked away at everything. We’re still left with poignancy, but it’s amidst this abstractly made film. It still makes coherent sense, and is shown in chronological order. Otherwise, Truffaut’s story would completely be incomprehensible. The jarring nature of Breathless is what is often lauded, but this disembowelment of a screenplay is part of what makes that unorthodox narrative work in this particular way. It’s not the taxidermy of another film, because there’s still a lot of soul left inside this feature. For me, it’s more like the shredding of a photo book’s pages that are then pasted back together in a new way. The images are still there, but they’re far from what they once were. Part of the appeal is the destruction of what once was, as you cannot notice the lack of wholeness in something that was never whole at all.

Michel at the start of the film.

Considering how Godard has written about film before he made Breathless, it’s safe to say that he completely understood the medium inside and out when making this masterwork. Ripping apart Truffaut’s story is one thing, but doing it right is another. The most obvious techniques used are the large amounts of unconventional cuts by editor Cécile Decugis (an iconic editor who worked on a number of French New Wave greats, including Truffaut’s The 400 Blows). Like Godard, Decugis had to know the capabilities of her field in order to shatter it. In Breathless, you have too many instances to bring up in an overall review (an entire article devoted towards the film’s editing would be needed), but I can still highlight some of my favourite examples: the breaking-up of a sentence into different clips, as if to mock the purpose of a montage or the passage of time, the sudden ends of scenes made by abrupt clipping, and the use of certain images to scoff at the viewer. For that last point, one key moment is the first kiss you see between Michel and Patricia (Seberg). The film cuts to a distant shot for this moment that most films swoop in to find. Part of this choppiness comes from Godard himself, who scrambled to eliminate enough of the film to cut the runtime down. Instead of taking away scenes, he sucked moments from particular scenes out. Deliberate poetry or accidental genius, Decugis’ and Godard’s work here ranks up there as the best editing work in a film of all time, and it isn’t even close.

Godard orchestrates Breathless in a similar way. In post modern fashion, you are made painfully aware that you are watching a film in quite astonishing ways. Early in the film, Michel asks what word is on the wall. The response is “Pourqoui?” (“Why?”), only for the camera to pan to the literal word “Pourquoi?” on the wall; his question was being answered, not combatted. Shortly afterwards, Michel’s exposition is spoken out loud, as if we are his imaginary passenger; the fourth wall gets broken quite a few times in Breathless, especially the final shot. On that note, we go back to the very first shot: the cartoon pinup and Michel’s rude self declaration. The rule being broken here is easing the audience into a cinematic world, so they feel comfortable enough to allow the illusions of filmmaking to reel them in. This includes the photographs that make moving images, the sound pairing up with the images, and the fluidity of pacing; all of these are tricks we have become used to with time, technology and experience. With that start, audiences of 1960 were tossed into the deep end, and unsure of what was going to come next.

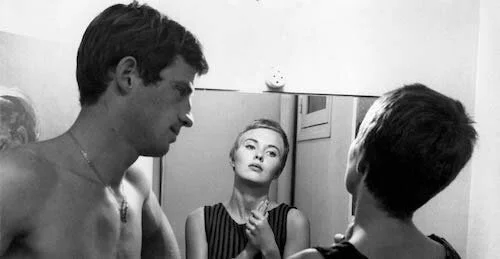

Michel and Patricia discussing their current situation.

At the heart of Breathless is a story about a wanted criminal on the run, finding solace in the apartment of the girl he loves. The way Godard presents the story renders this tale into a clashing of French and American ideals and filmmaking. Seberg’s thick American annunciation of her French dialogue is intentionally startling (she is presented as an American many times in the film). Michel likens himself to a poster of Humphrey Boghart, and tries to follow in the footsteps of the legend’s many gruff characters. Later in the film, Patricia brings up the name Ingrid, and I need not continue to explain the importance of this moniker when connected to Boghart. Breathless is not Casablanca in any way, although both leads are tethered to one single location for a majority of the film (in this case, it’s Patricia’s home). In a film about crime, killings and a fugitive, you spend an awful amount of time in a bedroom with trivial discussions. It’s fantastically unusual.

Godard’s level of unwonted filmmaking becomes an art in and of itself at certain times. A moment where Patricia and Michel squabble has both actors speak their points of view on top of one another. Patricia leaves the room, and the camera follows her, so Michel’s train of thought is left in the background; the subtitles follow Patricia as well. She arrives back at his vantage point, and he takes off, only for his conversation to be continued by Patricia this time around; this is the marriage of thoughts to create a dialogue. Initially, this was two monologues coexisting for a moment, and it’s exhilarating to watch for the first time. Even Godard’s cameo feels appropriately placed. He alerts the local police officers that he has seen where Michel has gone (without saying an audible word in front of us). The director is literally directing the plot in his own film. It can also be easy to read too deeply into a Godard film, but he invites us to analyze every single second of his works.

Patricia running to console Michel.

Breathless looks like it was shot on a portable Bolex camera. It is so shaky, dim, and nonprofessional in tone (it was actually a Cameflex camera that was used, and natural lighting and a wheelchair as a dolly to avoid major costs). All of the sound was done in post, with Godard tossing lines at the performers for them to recite (so Truffaut’s dialogue is even toyed with). It’s incredible how a film this detached from how motion pictures were being made in 1960 was so immediately beloved, let alone impactful. The magic is how the film starts off unsettling, but you get consumed by this new anarchistic format rather quickly. By the end of the film, it’s completely its own style. We end with a beautiful play-on-words that end up being our own little secret with the leads. Michel says “really disgusting”. Patricia doesn’t hear him properly, and so she is told Michel finds her disgusting. She doesn’t understand his usage of the word. There have been a number of translations of this ending, with “dégueulasse” being put as “scumbag”, “puke”, “louse”, and more.

Simply, Michel is meant to comment vaguely, and we’re not meant to be sure if he is criticizing the world or Patricia herself. Like an outsider viewing Breathless and commenting on the ugliness of the film. By the end, we stare in Jean Seberg’s eyes, with her thumb on her lips. We don’t understand what this ugliness is either. It could be us for liking the film. It could be the film itself. Either way, we have found life in a film that strived to strip then-modern film to its barest of bones. A crime film with a lack of major violence. Editing that is more noticeable than passive. Parallels that distract and not compliment. This is visual jazz (Martial Solal’s score is very fitting here) We are sixty years later celebrating the anniversary of Breathless, and it feels far more ahead of the game than most mainstream films today feel.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.