Eraserhead: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For March 19th and March 25th, we are going to have a look at Eraserhead

What I think needs to be brought up as a reminder when it comes to Eraserhead is how accidental it was in bridging arthouse experimentalism and the mainstream. David Lynch by no means was making an effort to reach the masses. He just wanted to make this film. Initially an art student — specializing in painting — that transferred into the American Film Institute, Lynch had a fascination for making art come to life. One of his earliest shorts Six Men Getting Sick is more of a moving illustration than an actual narrative. Influenced by the ghastly works of Francis Bacon from early on, Lynch adored the idea of having every feeling be felt but not necessarily understood. If you look up Bacon’s reinterpretation of Diego Velazquez’s Pope Innocent, you’ll see a confirmation of what the original painting looks like, but a drastic redesign that challenges the form and nature of the source material. Lynch works the same way. Blue Velvet is his bastardization of John Hughes high school flicks. Twin Peaks is his answer to daytime soap operas and nighttime cop serials. He loves these stories, and wants to show it in his own way. See his take on The Wizard of Oz and the film career of Elvis, known as Wild at Heart for more.

His earliest works even looked like Francis Bacon paintings. The Grandmother has pitch black backdrops, flushed out flesh, and the murkiest colours used to spruce up these shots. It’s life as we know it, but not how we know it. The ways Lynch tells his story on a literary level are also as familiar-yet-fragmented. The Grandmother features a troubled boy that creates a grandma figure from a plant he nurtures. Is this just some new grandmother, or the one he previously had and lost? That’s the power of Lynch’s idiosyncratic narrative powers. We barely question why a human is growing out of a plant based structure. We accepted that long before. We have other questions to have answered. These questions have less to do with why the hell we are watching odd things, but more in the line of wanting to understand this art we love even more. Even from his strangest shorts, Lynch was a cinematic powerhouse waiting to burst the film world open.

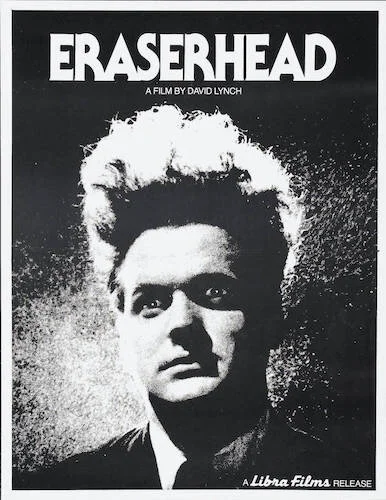

Henry, in a setting that is one thousand percent Lynchian over forty years later.

Studying at the AFI wasn’t going exactly how Lynch wanted it to (his output wasn’t really in line with the courses), but he felt an incentive to keep studying since he was guaranteed the chance to produce a script of his own choosing (including his own works). Right off the bat, making Eraserhead (which had a variety of different names and plots by the time it was fully realized) was something else the AFI didn’t quite get. It was too long to be an experimental short (then it was a few minutes long enough to be determined a feature), which meant that the institution felt being aimlessly led for that long just didn’t make sense. Once Eraserhead as we (kind of) know it was presented for the umpteenth time, all of the AFI board resented it once more, except for one person: Dean Frank Daniel, who demanded the film be made. What he saw in that screenplay I’m not quite sure, but it was the turning point that sent Eraserhead into production, and arthouse into the foreseeable mainstream.

Filming took ages. Lynch delivered newspapers and made more shorts in order to keep afloat. For the production, Eraserhead saw donations from Lynch regular Jack Fisk and his now-established wife Sissy Spacek (that certainly helps), amongst other sources. Lynch himself was there in the forefront the entire time: living in the sets as they were being built, to being in the sound booths to make sure each audible noise was just so. Credits wise, Lynch wrote, produced, directed, and edited the film, and helped with the score and sound editing and mixing. Perhaps it was the disbelief he had seen many times before that made him want to prove himself with Eraserhead first and foremost. While the film may be incredibly off putting to many, it is impossible to argue against the film’s incredible structure. The score is an experimental layering of sounds in a literal sense, and yet it is as soothing as it is frightening. The visuals are all suburban America, but done in a way that can nauseate you (these are all appliances we use, but they look so unnatural).

The “Man in the Planet” that sparks the gestation of the film.

Lynch has refuted claims that this film is about the horrors of parenting for the first time, but I’d also like to think that he is a bit in love with conflict enough to never admit when someone is right about his work. He does love having his audiences interpret his films and shows in their own way (he was an artist beforehand, after all). Plus, the signs are all there. A father-to-be, Henry (Jack Nance) is just plopped into this circumstance without any warning signs. His dinner with his girlfriend’s family goes terribly wrong (her mother tries to make a pass, the house is in the middle of an interpretive hell, and don’t even get me started on the chicken carving). He must marry girlfriend Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), and they have to make this baby thing work. There is no delivery time. The baby’s already here, and it looks demonic (to say the least). The majority of the film from here out is the turmoil caused by this situation: the fights, the lack of sleep, and the scariest baby in all of cinema.

But, if you want to take Lynch’s word for it, I personally see a deeper statement on the American dream from the eyes of Lynch (and Franz Kafka, of course). Henry’s parental woes are only the tip of the iceberg. He lives in a junk box in the middle of industrial nowhere. He is drawn to the “Lady in the Radiator” (who sings one of the most eerily beautiful songs in film history: “In Heaven”), and the “Beautiful Girl Across the Hall”. From the names alone, Henry has arguably the most normal name. Even Mary X foreshadows the difficult future of her and Henry’s relationship (but in a way that also gives her name mystique and unfamiliarity). His worst nightmare is being a part of the literal machine, with his decapitated head turned into erasers for pencils: he has been consumed by capitalist America, and treated as a non-human. Then again, we see his baby as a non-human before it even has a chance to live. We’re guilty as well.

The Lady in the Radiator crooning.

So, yeah. The baby is a major part of the plot, but not the entire story. Henry questions his roles as a father, but also as a member of society. The film is conjured up by “The Man in the Planet” (played by Fisk), and it’s as if he has summoned the soul of Henry to be today’s special program. Meanwhile, small creatures are worthy of being stomped on, white noise is the soundtrack of life, and the baby isn’t even fully formed and is dependant on its swaddle to even stay alive. Like a Francis Bacon painting, we’re seeing every day life here, no matter how hard we try to deny it. It just isn’t conventionally represented. It’s demented. Yet, I’d argue everyone’s complete interpretation of the film will differ from each other version even in the slightest of ways. That’s the brilliance of Lynch that has continued in the majority of his works ever since. There’s enough give for us to not be completely lost in the dark, and yet we don’t have all of the answers spoon fed to us. Is the Man in the Planet God? Is he an artist? Is he Lynch himself? Is he a board member of the AFI that ripped apart everything Lynch ever did? Who knows.

Eraserhead was finally brought to fruition, only for it to bomb upon initial release. Luckily, that isn’t the end of the story. Libra Films International, who distributed the film, began to approach the film as a midnight special; Ben Barenholtz of the distribution department convinced the Los Angeles theatre Cinema Village to follow suit in this model. Allegedly, this change happened on the 25th of the same month (around a week later). Of course, the rest is history. It became the go-to event of the midnight hour for over a year, and established a following that surpassed even a cult status. For crying out loud, this led to Lynch directing The Elephant Man, being a franchise hopeful for Dune (which he, to this day, regrets) and being approached for The Return of the Jedi (can you imagine a Lynchian Star Wars film?). In 2020, filmmakers like Shane Carruth, Michael Snow, and even a well known arthouse director like Terrence Malick, were never given these opportunities no matter what. Before then, I can’t imagine Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger or the like even being approached to do these works. Now, if they even wanted to is another question.

Henry with his sick baby.

Lynch never got complacent, though. However mainstream his works got, he still did things his way (see his insistence that Twin Peaks: The Return had to be fully his own vision). Ever since Eraserhead, there have been those that can grant him filmmaking powers that like what he’s doing, a repulsed crowd, and us: the hypnotized audience. The numbers of those that despise his works are dwindling. He somehow speaks universally for all of us; maybe it’s his conjuring of emotions without specific labels or guilt-tripping conventions. Something just clicked with Eraserhead that continues to click still; in that work, and in most of his works. Even amidst the most harrowing of abstract nightmares, we can be told that “everything is fine” by an unconventionally stunning angel made purposefully to look different. Henry’s finale is to pair up with this Lady in the Radiator and be consumed by distorted bliss. Is that death? Is that joy? Is that an awakening? It’s an indecipherable solace, but Lynch knew it would resonate as such to all of us. It’s true. In heaven, everything is fine. David Lynch has always been able to make an avant-garde cinematic (or televised) heaven that dabbles in hell, the subconscious, and the strangest oddities of life, and we’ve been fine ever since.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.