Acting Lesson 2: Voice in Film

Editor’s Note: Please take into consideration that any scene used as an example can be considered a potential spoiler to their respective films. Reader discretion is advised.

It’s difficult to pinpoint one specific source of inspiration or innovation when it comes to how voices have developed over the course of cinematic history. Obviously, there have been acting mediums before film came about (the most important one for our concern is theatre). Projection and line delivery was hardly a new invention, but cinema’s initial instances of these techniques are understandably muddled. Take this into account: film was a silent art form for many years. Even the earliest cases of recorded sound were either done as experiments, or in ways to enhance cinema in other ways (providing the surrounding sounds of a setting to create atmosphere). Sound was initially inserted as bursts, due to the difficulty of recording and the lack of efficient ways to implement sound just yet (either within filmmaking, or in the viewing experience, since many theatres didn’t carry the proper equipment to play sound early on). These short segments of sound were sometimes favoured for songs, as can be seen in The Jazz Singer (often credited as the first “talkie” ever, but it sure isn’t. It may have been a notable talkie when sound cinema was commercially reasonable to invest in, but many films, including Don Juan in 1926, came before it).

Once sound was being utilized in a larger capacity (as in being an important source of dialogue outside of title cards, or to accompany an entire feature film eventually), its as if talking in all different forms smashed against the wall at the same time, like a gym exercise where everyone tried to be first place. With limited recording technology (usually one microphone, fixed to a specific part of a room, and no major adjustments or time to ensure every sound is picked up properly), these early cases are quite abysmal to listen to. The sound is flat. Noises layer on top of one another. Worst of all — as far as this lesson is considered — is the talking. You can barely hear anything. Maybe with the comfort actors had with silent pictures (talking still existed, despite not being picked up in any way), these unconcerned habits made their way into the talkies era. There was still a lot to fix, but sound was the new hot topic in cinema. Changes could be made later. Studios had to have their sound pictures dominate theatres across the country.

So, we get films like this. I know I rag on The Broadway Melody often, but it remains a great educational tool for lessons on sound. This Best Picture winning musical was groundbreaking for its use of recorded sound (and its apparent colour sequence, which is considered lost). In 2020, we can watch a sequence like the one below, and pinpoint all of its issues.

There is expositional dialogue displayed here, and a good portion of it is nearly inaudible to us. How can we hear important information with the clatter of instruments, other voices, and ghastly acoustics? Of course, proper sound mixing and editing was nowhere near to be found in 1929, as the subject nowadays would be recorded, and the surrounding noises would likely be added in during post production. Since sound recording on a wide scale was a new discovery in the late ‘20s, proper protocols and etiquettes were still needing to be developed. If anything, this transitional period proved to be difficult for a number of working performers, particularly because they had a new hurdle to overcome. Voices didn’t matter in the silent years, and yet voices mattered more than ever at this point, especially since a great introduction to how a studio could utilize sound was needed. Which huge stars could leap into this new era and claim audiences everywhere? Buster Keaton (a silent film icon) had a notorious back-and-forth feud with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer once he signed with them in 1928. At first, he wanted to make the transition into sound, but the studio adhered. Once they finally accepted to make talkies on a wide scale, they provided him with the lines they wanted him to say, diminishing his on screen presence and his creative control he once had.

For other performers, they could strike while the iron was hot. Greta Garbo was a huge name in silent cinema, and her transition into talkies was one of the finest. English wasn’t her first language (she couldn’t even speak it five years before her first talkie), and originally her Swedish accent didn’t matter for her roles. Either way, she made an impactful statement in Anna Christie in 1930, as she commanded any scene she spoke in. Her voice boomed and matched her visual cues perfectly. Her first audible line in any film — an order of whiskey — was America’s opportunity to finally connect a voice to a person, and it did not disappoint. Not everyone had this smooth of a changeover (Garbo enjoyed a fruitful career until she quit acting in 1941). It still wasn’t perfect: Garbo had recorded a German take of every scene for German audiences, and a silent version was still shot so theatres without the proper equipment could still feature the film. For now, let us enjoy a make-or-break moment that defined the biggest shift in film.

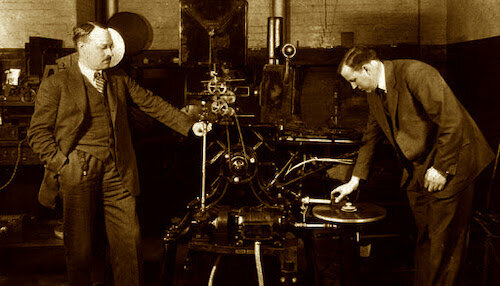

There were a number of recording techniques employed before this turning point, including the use of wax cylinders via phonographs. A popular method was using the Vitaphone, which I will let these original demonstrations teach in my place. I can’t explain it better, and it’s likely more fascinating to see a machine fulfil its duty whilst a lesson is taking place. These videos are courtesy of the Warner Bros. YouTube channel.

The Broadway Melody doesn’t seem to be too easy to laugh at anymore, right? There were many restraints to recording sound, including record size, the compression of all sounds into one streamlined noise, and a lack of organic comfort in recording (you couldn’t exactly move around or be natural, otherwise you may not be picked up). It also provides a major appreciation to those that did survive the transition, like Greta Garbo. To alleviate some of the lesson here, let’s enjoy an iconic scene from Singin’ in the Rain that has become a staple of lessons about the early days of talkies. Keep in mind this film is from 1952, and audio recording was in a much better state by this time.

Let’s get back to the origins of voice and film. As I discussed earlier, there was a lot of work needed to perfect voices. Greta Garbo was lovely to hear, but even she worked on her diction and projection later on in her career. For now, the wisest cause of action was to carry on with what was happening on the stage, as if there was never this gap between both acting art forms. By this time — the 1920’s and onward — a mutt of an accent was created because of stage productions. Known today as the Mid-Atlantic accent, it is a hybrid between British and American intonations (hence the name: as if an agreement was made midway across the Atlantic ocean). This was preferred, because it was actually being taught in various capacities, almost like an agreed-upon form of communication that created universal unity and professionalism at the same time (compare it to cursive writing, for instance). Theatre was more uniform for varying audiences. Radio couldn’t pick up deep bass tones at the time. Now, with audible film, these same theories were taken into account. Here’s a short educational clip, courtesy of BrainStuff - How Stuff Works.

It’s funny that the above lesson brings up His Girl Friday, because that’s a film I often associate with human speech and film. Unlike The Broadway Melody (which we can tear apart for educational purposes), His Girl Friday has aged considerably better with its now-unusual recording practices (particularly because of the comedic effect employed). Recording audio was difficult, as discussed, because of space; this also affected the budget of a production. So, screwball comedies like this Howard Hawks classic became iconic for the fast-paced delivery of information. It was a win-win situation: it was hilarious for audiences, and a money saver for studios. As well, we can really hear the Mid-Atlantic accent in all of its glory. Rosalind Russell was born in Connecticut, so her accent is one that was likely created by vocal coaches (not unlike the one you saw in a more humorous fashion in Singin’ in the Rain), acting schools and the like. Cary Grant is an England-born actor who made his way over into American films. You can almost hear the two different takes on an accent we have all clumped together since its extinction; perhaps there will be a greater appreciation for each different inflection.

The good news is that by this time magnetic tape was the preferred recording method for audio, and films like His Girl Friday weren’t being forced onto a record (thankfully). Still, like technology today, the medium was being perfected gradually as time went on; take into account microchip shrinkage with the ability to store more information that continues today. Over time, more and more elaborate recording could take place; two years before His Girl Friday, Listen, Darling was the first commercial film to use stereo sound. Imagine that. Nine years before this feat, sound was being crammed onto a single record with one microphone as an input. Now, multiple tracks could be used, and sound was only going to continue to get stronger. The crumbling, crisp recording noises of the ‘30s were soon to be replaced by the layerings of cinema’s newly evolving audible add-on, and sound was catching up to where on-screen developments currently were.

So, we return to the notion of the stage, particularly because this is where voice in film begins to get blurry. You can honestly focus on the countless different mechanisms and attempts from the earliest sound films until now, but I honestly don’t think it would help too much. I’m going to continue with the theatrical influences for now, because there was already a taste of this contribution with the Mid-Atlantic accent being incorporated. A certain go-to for the golden years of cinema’s marriage in theatre and film acting is Sir Laurence Olivier, who was one of the main forces behind the motion picture treatments of the works of William Shakespeare. An acclaimed stage performer (and often considered an all time great in acting), Olivier directed three of his own Shakespeare works, and took part in others. His first attempt was the Technicolor marvel Henry V, which plays into our chronology nicely; it was released in 1944, four years after His Girl Friday. Take note of his projection, and ability to command a scene even as the camera pulls away.

Performers like Olivier knew how to hit marks, whether it was the person furthest at the back of an auditorium, or a microphone (or two) in any direction. Of course, it’s impossible to say one person was the sole influence of the entire wave of acting from there on, but Olivier was a notable example of cinema’s early stages of evolution in the sound era because of his previous expertise (which became a definitive quality of the golden age of Hollywood). From here on out, we’re going to do some leaping, but I want to at least keep it somewhat relative to what we have discussed earlier. If there was ever an antithesis of Olivier’s that came shortly afterwards, it was Marlon Brando, who came from a new wave of actors. Brando studied under the guidelines of directors like Erwin Piscator, who veered away from the emotional resonance that theatre conjured with each and every syllable. Instead, the context of the scene, in which an actor can provide further detailing, was important. He continued towards this direction when he studied under Stella Adler, who employed the similar teachings of practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski, who favoured the experiences from within a scene over what a performer can extract from it. This lead to what is now infamously tossed-about: method acting.

In On the Waterfront, with what is often considered to be one of the greatest performances of all time, Brando’s signature slurred speech doesn’t get in the way of his acting in any way. However, it’s important to bring up here, for a few reasons. First, sound recording was only improving, as it always is. It was certain by now that performers didn’t have to lunge their voices towards a receptor, and that almost any delivered line would suffice if picked up properly. Secondly, here he is acting across Rod Steiger: another famous method actor, but clearly more of a student of the older ways in how he delivers his lines. Steiger has that oomph that the golden age of Hollywood carriers. Each of his words has to land. Brando, on the other hand, serves his lines with the scene’s best interests first, and leaves the classic forms of projection out of the equation (for the most part, as some projection is still ideal in any form of acting).

We’re at a place now where humanistic acting has been favoured for decades, sound recording, creation and mixing is only getting more fancy, and the struggles of before are no longer a threat. The only nagging constant factor is that sound is a separate recording than visuals (back then on film, now digital); even digital recordings will have a separate track for audio on most editing softwares. Luckily, this has worked in favour of many films, especially with the opportunity to do additional dialogue reads (or ADR for short). If a scene is unclear in the post-production process (when a film is being edited), a performer can be asked to quickly record a line in the studio, and presto! A line of dialogue will be seamlessly included in a scene when a character’s head is turned, so you can’t make the distinction that this was done separately. If anything, these lines can even be done in the comfort of one’s own home if absolutely necessary. Sure, sound is separate, but it’s no longer the pain it once was.

Still, we’ll flash back to a role of Laurence Olivier’s in 1972. Still employing his booming voice, here he is with Michael Caine (who also has theatre experience, I might add), who counters his acting approach drastically. Caine still delivers a fine performance, but it’s just easy to pinpoint the startling differences between how both actors hold a simple conversation. Olivier is bombastic and upfront, while Caine is more natural and introspective.

You can still find remnants of this type of diction in recent films, though its frequency as a preferred method of dialogue delivery seems to be thinning out (outside of Shakespearean or classic-driven films, anyway). For fun, let’s have a look at Paul Scofield: an actor who also was known for his Shakespeare expertise and his similarly commanding delivery of dialogue. As one of his final noteable performances, we’re rocketing all the way to 1994’s Quiz Show. Once again, like Michael Caine, Ralph Fiennes is a splendid actor, but it’s simple to see the different acting methods between both greats in this scene, especially now more than before (this was in the ‘90s, after all). Of course, the kind of diction and delivery that Fiennes uses here is mostly what many of us are used to, especially since it’s also one that translates well to the stage nonetheless (so it has overtaken many of the crossover voices we hear today). The days of Olivier’s and Scofield’s projection seem rather distant, due to the evolution of sound recording and its tribulations (no longer did we have to fight to be heard), and the transition of film as its own medium, separate from theatre.

Voice in film is extremely different now. In the days when thick accents like Greta Garbo’s could have ended careers, voice coaches to mimic accents are in demand now. The projection necessary to be picked up is now replaced with the ability to pick up the faintest of whispers. Voices are warped, manipulated, and experimented with in many ways, since recording is an integrated part of the filmmaking process, as fine tuned as any other step in a production. There is a whole palette of accents, deliveries, and timbres you can find now, although that Mid-Atlantic drawl remains elusive (outside of period pieces and caricatures, of course). From here on, the different voices in films is something you’ll just have to keep picking up on with every work you watch of any era. The origins of preferred methods were clear, but the plethora of paths afterwards make any definitive explanation futile. As a treat, I’ll end this lesson with Kenneth Branagh’s rendition of the exact same speech Laurence Olivier gave earlier in this masterclass, so you can get a sense of how sound recording changed the vocal delivery process entirely, and what a difference over forty years can make in cinema.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.