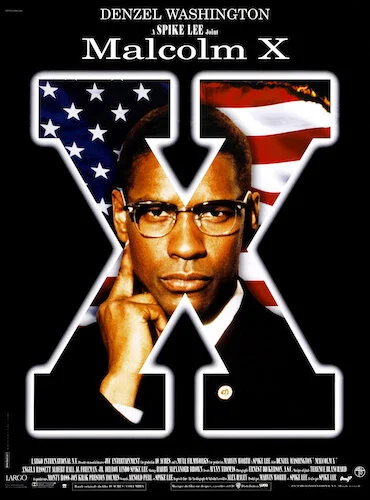

Malcolm X

May 19th is the birthday of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, also known as Malcolm X. Therefore, we are reviewing Spike Lee’s ambitious encapsulation of the activist’s life in cinematic form.

Much like the central figure of this biopic epic, the process leading up to Spike Lee’s masterful Malcolm X was full of controversy. Norman Jewison was petitioned against to step down from making the film; despite having been a supporter of marginalized communities numerous times in the past, he agreed with the outcry with this particular film. Lee, one of the biggest naysayers of Jewison’s attachment, stepped up and completely changed around the screenplay started by James Baldwin and Arnold Perl crafted almost two decades earlier; the changes were so drastic, Baldwin’s estate asked for his name to be removed from the production. Nevertheless, a big reason why Jewison was asked to step away was that many felt an African American filmmaker should have worked on the film.

Lee, however, was also doubted, because of his style of filmmaking, which doesn’t shy away from harsh realities. Malcolm X supporters feared that he would be portrayed in a bad light if Lee made the film. Lee was reportedly nervous about the eventual response of his film, even though he felt like it was the film he was born to make. Warner Bros. disagreed, as Lee’s vision ended up costing millions more than the studio was willing to give; Lee and a number of his famous friends (Oprah, Magic Johnson, Prince, and more) pitched in to continue the production. During the press rounds for this film, Lee infamously asked for black reporters to cover the film first. It’s a statement he would have to refine.

At the end of the day, Malcolm X decades later reveals the obviousness of this whole situation. This film could only be made by Spike Lee. The petitioning for a black filmmaker is because a white director would likely have gone with the skewed version of the activist that was being taught in schools (this also explains Lee’s reservation for non-black critics covering the film initially). However, Lee himself is the kind of filmmaker who wouldn’t sugar coat films either, so Malcolm X’s blemishes are as clear as day in this film as well. If the proper story is to be told, then it has to be told right. Aside from the creation of characters and the occasional alteration, Malcolm X is as upfront as you can get with such a complicated story. It’s well over three hours long, but not a single second feels like it is out of place. It’s evident that this is exactly the tale that Spike Lee wanted to tell, because every single moment is important, and used to deliver the proper backstory of one of history’s most polarizing figures. You get a neutral look at both sides from the perspective of a black artist that is personally grateful for the focus on racial prejudice that Malcolm X refused to turn a blind eye to.

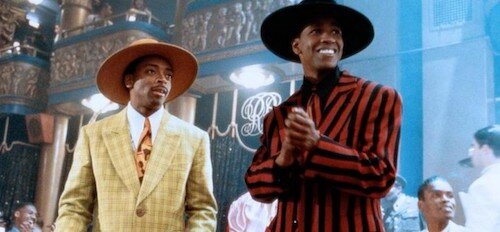

Back when Malcolm X was Malcolm Little.

Malcolm X details as much as possible without feeling overlong: Malcolm X’s difficult upbringing and years of struggles. There is simply too much to cover in a simple review, but Lee’s focuses in the film are, dare I say it, tasteful. Sure, Lee is more synonymous with intense and bold, but I’d like to point out that the amount of central lack of bias found is apposite here. A particular moment that sticks out is when Malcolm X, then Malcolm Little, is asked if a single “white man” had never been the devil to him by the fictitious character Baines, and the sequence cycles through familiar faces we’ve seen previously in the film; the collage hesitates on the final image of ex-girlfriend Sophia as a clear indication that surely not everyone can be considered evil. Without forcing Malcolm to say something silly, or Lee clouding the moment in a confused way, a simple image is enough. The context of Malcolm X’s life and teachings is already challenging enough to display without stepping on any toes. Going the extra mile to portray his internal conflicts is another story.

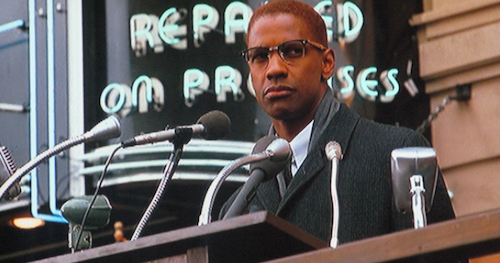

This is a testament to Lee’s expertise in filmmaking, which deserves to be discussed as much as possible in film schools everywhere. So many clever tropes and decisions are included in Malcolm X; it was never going to fall into typical bio-epic territory, but Lee going the extra mile makes this film stand out even more. I’m talking about the numbers montage, the mirroring between Malcolm’s family’s home invasions from both his youth and his adulthood, and the incredibly brave ending, where Malcolm X portrayed by Denzel Washington is gone for good after his assassination; the rest of the film is devoted to real footage, and meta discussions of his legacy in docudrama fashion.

People don’t discuss Lee’s adoration for film nearly as much as they like to complain about him, which is a shame. The first act with Malcolm Little’s teen and young adult years being shot in sepia like The Godfather feels like a comparison of someone trying to get by, being broken by their environment. Whereas Michael Corleone shatters and turns into a monster, Malcolm X fights to try and pave a path with his anguish. Then there’s the assassination, which remains a definitively impactful moment of the ‘90s, neither glossed over or glorified; it’s as raw as necessary. It’s straight out of the Martin Scorsese lessons that he attended. Lee’s love of film is forever on his sleeves.

Malcolm X as portrayed by Denzel Washington.

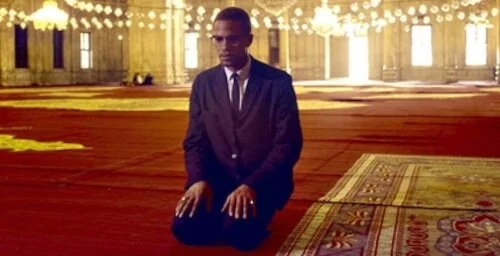

Speaking of Denzel Washington, it is virtually impossible to discuss this film without bringing up the bravura performance that is considerably the highlight of an already illustrious career. It may be easy to highlight Washington’s likeliness with Malcolm X, especially during his speeches, but that would be detrimental to the entire rest of the film. What about his years as Malcolm Little? The prison scenes, especially in isolation? His trip to Mecca to experience a personal regrowth? There are countless moments here that are all Washington, using each and every opportunity to shine in one of cinema’s finest performances of all time. As much as this role is great because of Washington’s ability to change into the late activist entirely, it’s also thanks to his ability to read exactly what scenes need. On the other hand, as much as one can call this film Washington’s moment, it’s completely wrong to consider this only his film, and thus Malcolm X is far from an acting vehicle. This is due to the amount of artistry at play here, matching Washington’s caliber of acting. Neither outshine one another. We instead get a completely preeminent biopic, where box office numbers aren’t the focus whatsoever. I’d go through the supporting cast as well, but there is far too much to say. Just know that everyone here is superb, ranging from Angela Bassett’s unabashedly sincere performance, to Delroy Lindo’s commanding work.

The amount of juggling of themes makes Malcolm X a cinematic marvel, and most certainly one of Spike Lee’s greatest achievements. If you thought getting to production was enough of an achievement, then Lee’s ability to present a neutral film that still has something to say for over three hours is a miracle. Not once does Malcolm X feel like it is forcing you to feel a certain way, even with the figure at the centre of the film. Not once for over three hours. We see Malcolm X’s transformation due to his Islamic awakening, and him furthering his self realizations by diving deeper and deeper into his religion. We get the sense that Malcolm X was going to continue growing even well after the last time we see him, but his assassination stopped us from ever finding out.

Malcolm X praying while at Mecca.

Ten years ago, Spike Lee’s greatest aspiration was preserved by the Library of Congress for its contributions to film and history. In every single way, this honour is rightfully earned. As a film in its purest form, Malcolm X is an array of dazzling artistry, especially at the hands of a cinephile filmmaker that dared to tell this tale in his own unique unprecedented way; it’s a style straight out of film school, but Lee has his own voice that remains singular regardless. As a film about El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz in all of his lives and rebirths, Malcolm X is as unbiased as a film can get, without completely becoming numb and void of a tone. Yet, despite all of this, I still feel that the film is underrated.

Doing a quick search of current reception of the film claims Malcolm X is conventional biopic fodder. I couldn’t disagree more. It’s common historical knowledge that Malcolm X was executed. For over three hours, I was so hooked by this historical depiction crafted by Spike Lee and company, that I was still devastated by the inevitable, as I wished for more societal and personal change to occur. With Lee’s signature bite, Malcolm X is riveting through and through. If a critic wishes to misunderstand a streamlined storyline — stuffed with creative decisions and challenging discussions to boot — as conventional, then that’s their loss. For me, Spike Lee’s Malcolm X is one of the finest biographical epics to ever hit the screen.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.