The Best 100 Films of the 1990's

WRITTEN BY ANDREAS BABIOLAKIS

Thirty years ago marked the ten-year countdown to the new millennium. The neon colours of the ‘80s transformed into a wave of highlighter hues. Video games felt like they leapt off the screen, being 3-dimensional for the first time. Compact discs completely took off as the go-to method of music, games, and eventually even motion pictures. Dial-up internet took an eternity to even start up, probably because your sibling won’t get off the phone; you just want to play flash games! When it comes to the entertainment based technology that we know and love now, the 1990’s were a simpler time. Fashion was unparalleled, though. Whatever leftover itches (from previous eras) we had for crazy colours and patterns were dealt with within these ten years, and it was glorious.

The final era of children playing outside more than indoors. The turning point of how we received news. The dawning of mobile phones taking off, transforming how we communicated. There was an undeniable shift these last ten years of the millennium. Maybe it was out of fear: what if Y2K did happen? Maybe it was out of anticipation: a new millennium calls for the utmost amount of innovation. Either way, the gradual preparation of a decade’s self for the upcoming new age can be found all over these one hundred films listed below. Whether it’s the dusting off of the vibrant ‘80s, or the rehearsals to become the future in the ‘00s, the greatest works of this era are the beautiful offspring in between: aesthetic, sleek, and audacious.

These one hundred works represent shifting social and political tides, contrastive works (meant to offset some of the safer mainstream films being released during this time), and obsessions with colour (you’ll eventually come across a string of “red” related films; it was unintentional, I swear!). The ‘90s was an interesting time: it feels like the first real moment (working in reverse order, of course) where past masters and then-prodigies clashes together, creating the insanely difficult task of limiting this list to just one hundred titles. I cut a plethora of favourites; some may be yours, and many were definitely mine. I also understand that this decade is meaningful to many of you, as I start to dig deeply into the childhoods and fond memories of our readers (which will only continue for a while, the further back we go). I hope you understand that going forward. For us, as challenging as this was, it only means that I am even more confident in the selected works that made the cut. Here are the best one hundred films of the 1990’s.

Disclaimer: I haven’t included documentaries, or any film that is considerably enough of a documentary (mockumentaries don’t count). I haven’t forgotten about films like Close-Up or Paris is Burning. I’m keeping them in mind for later (wink wink).

Be sure to check out my other Best 100 lists of every decade here.

100. Ed Wood

Tim Burton operated at his very best with this completely honest homage to a previously maligned filmmaker. Before the days of the internet, people would rely on word-of-mouth without looking up work for themselves. It was easy to just assume Ed Wood was terrible and call it a day, especially with his work being chastised on such a public forum. Not for fellow cinematic misfit Burton, though. Ed Wood was an earnest biopic that, sure, laughed at the terrible results the late filmmaker concocted (as well as the insane stories behind these films), but it was such a loving introduction to someone previously crowned the worst filmmaker of all time. Is a director with such a passion for the craft really that bad? Can all of us safely say we can come up with better? Ed Wood balances the fun it pokes and the heart the Plan 9 visionary had that was heavily overlooked previously.

99. My Own Private Idaho

One of River Phoenix’s final hurrahs before his untimely passing, My Own Private Idaho was Gus Van Sant’s way of coupling two of the decade’s early icons in a candid road film (the other, obviously, being Keanu Reeves). Told from the perspective of a vagabond gigolo with narcolepsy, My Own Private Idaho is dissociated enough to be noticeable; these are stories meant to be told by troubled youths that not many want to hear. As unique as the film is presented at times, it’s also incredibly introspective when it needs to be (I don’t have to bring up the campfire scene more than I just have for those feelings to rush back). My Own Private Idaho is shot and edited as messily as the world that surrounds the two leads, and solace is only figurative when the world has been cruel too many times.

98. Lost Highway

The ‘90s were a bit of an interesting period for David Lynch. Outside of the show Twin Peaks, he had three different films that pushed and attracted audiences alike. There’s the Elvis film gone possessed Wild at Heart, and then the Twin Peaks prequel Fire Walk With Me. Both are fine films, but my selection is the topsy turvy Lost Highway, which has only aged better and better with time, given the shifting perspectives of Lynch’s works and influence. The fragmented and brooding nature can be found in many films today. Besides, it’s Lynch’s interesting approach to likening the role of an actor to the different hats people put on in society, as if we take on new lives (he takes this to a literal extreme in his fugitive story). If we can change our natures, why can’t time? Thus, we get Lost Highway: a perplexing story that is as alluring as it is frightening.

97. Toy Story 2

After the underrated A Bug’s Life (Pixar’s nod to Seven Samurai), the then-fresh studio realized their best bet was to keep doing what they were born to do: create stories about a child’s playthings. Toy Story 2 adds a dash of narrative complexity to the similar formula (if only late ‘90s us knew they would attempt, and nail, a nearly identical story twice more). This time, the toys — especially Woody — are becoming familiar with their legacies outside of Andy’s imagination. While a bit caught up in some of the ‘90s trends (including a blooper real in an animated film), Toy Story 2 was still a rare sequel that worked wonders, and ended the decade off for Pixar on quite the high note. To think it was only the second stop in a fantastic tetralogy.

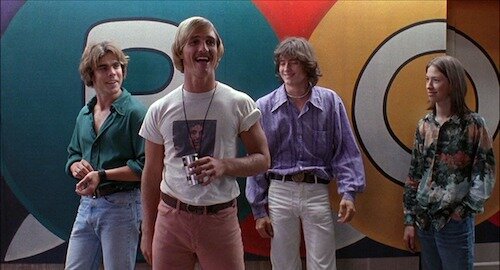

96. Dazed and Confused

After the indie hit Slacker, Richard Linklater had to prove that his vagabond ramblings had to mean something. Enter Dazed and Confused: a trip even further down the care-free rabbit hole, that somehow has itself more put together than a number of its partying characters. Introducing the world to lazy America’s answer to French New Wave filmmakers like François Truffaut, Linklater proved that he was far smarter than he may have appeared back in 93, especially with this deceptively shallow film. On the surface, Dazed and Confused is just a high school comedy mingling with the others in the ‘90s. Dig a bit deeper, and you see a refusal of conformity, even during a night where all teenagers are banding to party (even against one another). It’s a dramatically ironic experience. We can see the hazy futures, but these characters are all about this moment that the film provides them for just under two hours.

95. Ratcatcher

What a promising start to Lynne Ramsay’s career. Ratcatcher is the definition of ‘90s independent cinema, thanks to Ramsay’s ability to extract so much substance out of a Glaswegian ghetto. Utilizing this opportunity to break cinematic conventions here and there (could we ever forget the astronaut mouse sequence?), Ratcatcher is as invested in a new world as it is a statement on the current one. Ratcatcher is less of a story than it is a predicament, and you endure it for just over an hour and a half. It may feel like an eternity, only because of how upfront the film is about these horrid living conditions. This says much more than spinning together a conventional story would have, and Ramsay knocked this study out of the park.

94. The Puppetmaster

Possibly one of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s riskiest films (and that is saying a lot), The Puppetmaster is about, well, a puppeteer, during the years of Japanese Taiwan. The film is static with its lengthy shots, as if we are looking into a cinematic puppet show of our own. At two and a half hours, it’s easy to get lost in this film, including the moments where puppeteer Li Tien-lu conducts his own shows; it’s almost like watching puppets operate puppets. Seeing the political paradigms at the time portrayed in such a way is like watching a filmmaker truly command all of the players and pieces by hand, like he is delicately taking care of the legacy of an important historical figure (which, essentially, he is). Without getting too surreal, The Puppetmaster resonates as a performance piece by a perfectionist filmmaker.

93. Toy Story

Here’s where it all started for Pixar and the Toy Story saga. The first completely computer generated animated feature film, and it was a bar set incredibly high. Toy Story is the rare achievement of a children’s film void of complexity that isn't completely hollow. It’s impressionable, because it’s basic enough to appeal to all of the kids that watched it; what if our toys came to life when we left the room? The film is so pure, no amount of poor aging in the textures can change just how magical the whole experience remains. When Buzz Lightyear yells his famous, paradoxical line “To infinity and beyond!”, we now know that this was both Pixar and the Toy Story series’ motto from the beginning. These aspirations are why the film remains purely fantastic.

92. Léolo

The last feature we ever got to see from the late Montrealian artist Jean-Claude Lauzon, Léolo is a coming-of-age film that those that are coming-of-age may not get, unless they are wise beyond their years. It rolls around in the awkwardness of self discovery during puberty beyond almost any film we’ve ever witnessed. Told from the perspective of a naive, sexually awakened tween, Léolo ventures down some very uncomfortable territory, all in the name of an authentically youthful look at life’s biggest oddities. Parts bizarre, yet wholly riveting, Léolo is as visceral as an arthouse tale of childhood can get, and it all starts with the belief that the titular boy’s life started when his mother fell on top of a stained tomato; just like life, the film only gets stranger.

91. Jackie Brown

If Quentin Tarantino could ever have an underrated film, it would be Jackie Brown. After the success of Pulp Fiction, this comedy noir was Tarantino’s excuse to work with his icons of yesteryear. Parts were written specifically for Pam Grier and Robert Forster, while Robert DeNiro and Michael Keaton were encouraged to stick around. We get the slowest burn of any Tarantino film, accompanied by fascinating and strange characters (let’s not forget the return of Samuel L. Jackson, this time as a bizarre gun runner). Invested more in the heat of each moment rather than the unpredictability of twists, Jackie Brown may continue to still be misunderstood. For us, it’s a badass who wants to put an end to her cul-de-sac life — being taken advantage of by criminals and society — for good, and every step of the way is empowering.

90. π

The introduction the world had to future troublemaker Darren Aronofsky was this philosophical disaster known as π. It’s tempting to call this debut pretentious, but it’s so self hateful that we just can’t. It doesn’t fully believe the crazy, conspiracy inner workings main character Max Cohen is thrust upon, but it leads us to believe that Cohen himself does. The goal shifts from realization to curing damnation at any cost, even if it means the removal of one’s genius. Being so removed from the massive amounts of information and discovery helps make π as engaging as it is. We can appreciate the societal and personal downfalls shoved into a film that’s less than ninety minutes long. It’s brief, but π contains entire lifetimes and eternities.

89. Miller’s Crossing

We might be used to the Coen brothers operating with many genres at once, so looking back at Miller’s Crossing may feel a bit strange. I’d argue that this neo-noir thriller is the iconic duo trying to focus entirely on making a beautiful film. The dark humour, southern quirkiness, and identity twists all take a major backseat for this film’s straight forward darkness and cinematic brilliance. As a result, Miller’s Crossing has become both a dark horse and a championed work by Coen aficionados across the board; as you can see, we’re part of the group that adores this film. It’s unusual to see the Coens being so stylish, but it’s a treat if I ever saw one.

88. The Virgin Suicides

The amount of pressure that Sofia Coppola may have felt during the making of The Virgin Suicides is nowhere present in the final result. Being the child of a New Hollywood legend, and being mocked out of an acting career after The Godfather Part III couldn’t be easy. Yet, you watch a film like The Virgin Suicides, which is considerably dark in subject matter, and her filmmaking seems effortless. Featuring a lush score by French chill pop legends Air, and tender performances from veterans and newcomers alike, The Virgin Suicides is grim only when the story calls for such an emotion. Otherwise, it’s a hallucinatory vision conjured by sheltered daughters about high school life, and the inevitability of death. Sofia Coppola needn’t be compared to her father ever again. She proved her immense talent and signature strength within just one hundred blissful minutes.

87. Cold Water

Something about Olivier Assayas seems contrarian even if he isn’t trying to be. At his most personal, Cold Water is still a rebellion against cinema’s most basic conventions. Reportedly inspired by his own youth, the film’s Gilles goes the extra mile by projecting, perhaps, how Assayas foresaw he would have been at that age, had he continued that same trajectory of misbehaviour. Accidentally casting then-rising star Virginie Ledoyen (he opted for an unknown cast) helped anchor Cold Water a little bit; some experience feels necessary in a film that focuses so much on doing the opposite of pedestrian (and a seasoned star can effectively go against her own usual practices). Cold Water is the dive into adulthood to escape adolescence, only to learn that the unknown may be less friendly than being told what to do.

86. Gummo

Perhaps the least friendly film of the ‘90s, Harmony Korine gives absolutely zero damns about holding your hand. I don’t even know if he aimed to tell a story whatsoever with this setting-obsessed film, that’s more concerned with the after effects of a natural disaster in a poor town than who these souls are as people. That’s what keeps Gummo so polarizing. It’s an absolute spectacle at planting you amidst this end-result, but you won’t get any leeway if you dig deeper into the narrative. What I can safely say is Gummo as a film is as unorthodox as the neglected town that has to rely on its own devices, transmogrifying citizens into liars, abusers, and damaged souls.

85. Little Women

I sure love Greta Gerwig’s refreshing take on the Louisa May Alcott classic, but I still must show adoration for Gillian Armstrong’s perfecting of the source material in its own traditional way. Shifting more of the focus on Jo March this time around, Armstrong’s Little Women is crafted to feel like more of a personable tale from the perspective of the very writer of these two volumes. It’s an edifying experience that still manages to standout from the plethora of “safe" films one can find in the 1990’s, possibly because of Alcott’s timely storytelling, the warm acting from all involved, or Armstrong’s tender representation of an impressionable tale.

84. Happy Together

The ‘90s were a hell of a decade for Wong Kar-wai (you will see a handful of his other works on this list). Rarely does a filmmaker churn out so many era defining works in such a short amount of time. Then, there’s Happy Together to wrap the ‘90s off by going heavily against a heavily censored industry. Luckily, it seems as though the film went relatively unscathed, so the world was gifted this touching romantic drama about a failing, forbidden relationship. Featuring Kar-wai’s usual obsession with aesthetics, Happy Together is a reminder that love based hardships can still sour the most beautiful of worlds around you; what good is the world if the one you love is dissipating from your heart?

83. Dead Man

With the resurgence of western films in the ‘90s, Jim Jarmusch had to hop onto the bandwagon in his own bizarre, awesome way. Dead Man is a trippy take on the wild west shot in gorgeous black and white, and featuring Neil Young making up the film’s score on the spot (it’s occasionally funny to hear Young start noodling on his guitar and abruptly stop, but it's evident that he can create gold out of thin air). As deep as it is strange, Dead Man is like listening to tall tales while strung out on peyote. Now this is why the genre needed a come back; clearly visions were meant to be shared still.

82. Irma Vep

What a meta cluster. Olivier Assayas channels Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Beware of a Holy Whore, and accidentally brings Day for Night into the picture as well (casting Jean-Pierre Léaud likely didn’t help with these comparisons). He does this in an effort to create a fictitious remake of Les vampires, starring Hong Kong sensation Maggie Cheung as herself (in Irma Vep, not in the remake). It’s confusing on paper, but perfectly streamlined within the film. With backwards critics that are clouded by bigotry (claiming Cheung doesn’t represent French cinema) to cohorts that treat her like an untouchable being, Maggie Cheung is stuck in the middle of this francophone miasma, unsure of what exactly is going on (she just wants to do her job). Irma Vep ends with a similarly puzzled shrug: a film-within-a-film that is parts mesmerizing, and parts insane. Now that’s how you stick it to French film critics, whilst being exactly the kind of feature they would likely love.

81. Only Yesterday

Given new life by a theatrical run in the last few years, thanks to the 25th anniversary English dub run (including Dev Patel and Daisy Ridley), Isao Takahata’s Studio Ghibli classic is more discussed now than ever before. Even the film in its most original form (fully in Japanese, not remastered) is exquisitely animated enough to not even tell that it’s nearly thirty years old at this point. It’s also incredibly progressive, using the animated medium to convey a feminist tale of self identity and growth (cutting between Taeko’s childhood and her adult years looking back). Only Yesterday is both stunning and forward thinking, and it’s destined to continue to be timeless.

80. Heat

The opportunity to have Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro on screen at the same time could have easily been squandered, especially in the ‘90s (let’s be honest here). However, Michael Mann was decidedly calculative in his approach to this rare instance. Heat takes its time to unravel, allowing the tone of the corrupt setting and the dismal players to really sink in. When it’s go time, even the action isn’t wasted, with some superb choreography, and live recording of these sequences (so gun shots sound frighteningly loud, and bullet shell casings are audible garnishes for this carnage dish). Heat is compelling first and foremost, and it plays in favour of the film’s heaviness.

79. Europa Europa

Agnieszka Holland handled Solomon Perel’s memoirs with complete delicacy, particularly because of the astonishing nature of his tales. Holland was a Jew during Holocaust Germany that managed to survive by passing off as purely German amongst his Nazi captives (who swiftly enlisted him after realizing their “mistake”). Holland’s Europa Europa captures this exhilarating true story with so many minor details amongst the permanent panic. Instead of lionizing this phenomenal slice of history, Holland allows Perel’s words (and lead actor Marco Hofschneider) to do their work. Part triumph and part tragedy, Europa Europa is the kind of real miracle that luckily wasn’t spoiled in the filmmaking process.

78. La Belle Noiseuse

A few French New Wave filmmakers that continued into the ‘90s will appear here, including Jacques Rivette. Known for being one of the more experimental minds of this movement, Rivette has always adored testing limits. La Belle Noiseuse may be his perfect balance of give-and-take. At around four hours long, at least twenty five percent of this film is devoted to watching an artist sketch. Without cutting away, we slowly see works of art be created. We never really see any end results, which is when you realize what Rivette is getting at. La Belle Noiseuse is obsessed with the artistic process more than the impressionable end result, allowing its full form to be built by ongoing processes rather than the illusion of completed works (where every little brushstroke vanishes into a whole). The film itself operates the same, daring way, and you’ll rarely find an experimental film as open about this meta nature as La Belle Noiseuse is.

77. Babe

It’s not common for a family film to be as technically astounding and narratively compelling as Chris Noonan’s sheep-pig fable Babe. Think about it. The film is twenty five years old now, and it remains one of the technical achievements of the ‘90s (not to mention how well done the talking animal illusions still are). For a film meant for families to enjoy, Babe is fantastically shot, well edited, and many other notable traits. It doesn't hurt that the heartfelt story between an aspiring piglet and a jaded farmer (in much need of a boost of optimism) is so charming. A quarter of a century later, all I can say about Babe and its fine work is “That’ll do, pig. That’ll do.”

76. The Sweet Hereafter

It’s strange to remember that a Canadian indie film went up against James Cameron and Titanic for Best Director at the 1998 Academy Awards ceremony. Often considered one of the finest Canadian films ever, Atom Egoyan’s legal drama The Sweet Hereafter is a little experimental to the point of idiosyncrasy; metaphors surpass literal natures at any given time. Featuring one veteran face (Ian Holm) and a gang of Canadian icons and newcomers, this outlier perspective of a national crisis is entrenched in the damnation of guilt and judgment. At the end of the day, choosing what is ethically just is incredibly hard. Egoyan showcased this dilemma with good ol’ Canadian grace.

75. The Truman Show

The ‘90s saw the releases of a number of philosophical works (some made this list, and others sadly didn’t), but the greatest of these examples — particularly in both an accessible and a defined sense — is The Truman Show. Slowly uncovering the unique premise as the titular Truman (Burbank) begins to grow wise to his surroundings is part of the appeal, particularly because the film reveals more to us than Truman at any given time. Seeing an entire world be deconstructed is one thing; having all of the creative film/television set parallels is half the fun. Then comes the depth of The Truman Show: the centred questions about perspective, the morality in filming an unknown participant’s entire life, and the job qualifications of artists forced to partake in a sadistic experiment.

74. Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

Jim Jarmusch can't just make a hitman film. He has to channel Le Samouraï in a bit of a literal sense, by turning the main character into an actual samurai (of sorts), and hiring Wu-Tang Clan veteran RZA to conjure some 36 Chamber styled beats for the film's score. Mixing spiritualism with bloodshed, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai is cool yet profound. Ghost Dog is usually ten paces forwards, even with the film's audience, so we can get a sense of his wits. With peace comes tragedy, and even Jarmusch and company know this, so Ghost Dog’s own sacrifices help to balance the narrative out. Yet, it remains one of the slickest ‘90s cinematic experiences.

73. Beauty and the Beast

A tale as old as time. The Little Mermaid sparked the start of the Disney renaissance period that would last for around ten years; this era solidified Disney as the animation super behemoth that we would eventually see it as today. If there was a particular film that first rendered the company as a critical force to be reckoned with, it would be Beauty and the Beast. The perfect blending of magical whimsy and artistic expression, this Disney output was the first real sign of spectacular things ahead. Containing (arguably) the greatest Disney collection of songs, and the most consistent amount of emotional resonance, Beauty and the Beast was a raised bar for the medium; it stays an animated classic today, having lost not a single speck of its splendour.

72. Three Colours: White

Despite being the weakest entry in the Three Colours trilogy, White is still a clever effort that’s been branded by Krzysztof Kieślowski himself as an anti-comedy. Representing the never-perfect natures of equality in a flawed society, the film is frankly dismal as a feel-good flick, but invigorating as the most loving tale of revenge. Given its status within the trilogy, I think White is gravely misunderstood. It might not be as stimulating as Blue or Red, but it’s just as intelligent, and each subsequent viewing of the film is even more rewarding than the first time through. For a middle part in a fantastic series, White does everything it needs to do in order to continue the trilogy, and remain individualistic.

71. Saving Private Ryan

Even if you were to, say, not like the rest of Steven Spielberg’s army opus Saving Private Ryan, it’s borderline impossible to write off the opening thirty minute sequence in any way, shape or form. Fortunately, the rest of this sacrificial rescue mission holds up, thanks to consistent cinematic effectiveness. With the focus on what one life means to loved ones everywhere, Saving Private Ryan never loses sight of this notion, or becomes melodramatic about its mission. To save the titular private is to — in a sense — save humanity; to instil a positivity via ripple effect within one’s self, the person rescued, and all surrounding them. Amidst the gruesome bloodshed that the film refuses to shy away from is a glimpse of hope, either in Tom Hanks’ angelic self, John Williams’ warm score, or Spielberg’s refusal to ever remain completely cynical.

70. Audition

Apparently, at one of the film festivals that Takashi Miike showed Audition (one of his over one hundred films), a patron stormed out and declared he was a sick man. This could be because the entire first half of Audition is staged to look like a romantic drama (outside of one weird moment, but maybe it can be missed if one goes to the bathroom). Then, the real film begins: one of the most disturbing achievements of the 1990’s. Not as much of a genre bender as it is a genre takeover, Audition is the search for love — through a fictitious acting audition — that goes disastrously wrong (I really can’t say how here). One can only imagine what Miike and company could say about today’s society, where love is found online. For the ‘90s, Audition did not try to portend the future of connectivity, but it did remind us that first impressions are unreadable for how psychopaths are deep down.

69. Before Sunrise

So this is where it all started. As I have hosted my top 100 films of each decade, we have slowly gone backwards in the Before trilogy with Celine and Jesse. Before Midnight saw trouble in paradise, after a partnership predictably (by the power couple) ran into conventional marriage struggles. Before Sunset was the moment of doubt, where a fleeting experience was questioned by a later experience. Before Sunrise, however, was the heartfelt beginning, where almost nothing could go wrong. The title is clever, because it marks the start of the “day” of this journey; it also harkens back to F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (before the marriage in that film became broken), as Richard Linklater’s 1995 cinematic poem resembles much of the bonding in that silent classic. Before Sunrise is sweet on its own, but all the more powerful within this outstanding trilogy.

68. Sense and Sensibility

Ang Lee and Emma Thompson couldn't have worked on a more aptly named Jane Austen novel. Thompson adapted Sense and Sensibility to such a modern level without sacrificing any of the original source’s magnetism. If Thompson’s conversion was the sense, then Lee’s tender filmmaking was the sensibility, as he merges all of the glamour and unrest together effortlessly. A benchmark film for the wave of ‘90s period piece works that tried to follow suit (especially the Austen adaptations to come), Sense and Sensibility was operating via its own terms, hence why it remains the standout work. As Thompson’s debut screenplay and Lee’s first entirely English-language film, Sense and Sensibility is a partnership into the unknown that never felt anything less than confident of its strengths.

67. Living in Oblivion

If The Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie was made for people in the film industry, it would be Living in Oblivion. For the entire duration, a filmmaker, his cast and crew, suffer a production that will not go right for one second. Then, the surreal begins: players begin to wake up. Nothing had happened. Well, they kind of did the day before, but in a different way, and we are seeing the after effects. Still, nothing is going right. If you don’t work in film, Living in Oblivion is an educational comedy about what can go wrong in this field. If you do, well, this is a nightmare come true. Even the glimpse of something going right isn’t exactly a victory. There’s still an entire remainder of a shoot to go. This is only to conclude this torture. It’s too bad, because I’m sure ten hours of Living in Oblivion would be fodder for our hunger for laughs.

66. Center Stage

Parts of Stanley Kwan’s Center Stage are documentary interviews conducted by him with the cast and crew of this very film. Maggie Cheung — who plays silent film sensation Ruan Ling-yu — answers questions about the very person she plays. Then, the film cuts to biographical picture depictions of the Chinese acting legend. The further the film goes, the less we see Kwan and his team enjoy life; the film dissipates into all of Ling-yu’s sets and homes. For the final act, Center Stage begins to stall surrounding Ling-yu’s suicide (posed at the start of the film), as if the film itself cannot carry this tragedy out. It reverts back to an interview style, then becomes a metaphysical shoot-within-a-shoot. It does all that it can to survive, and give Ruan Ling-yu the legacy she deserves. With Maggie Cheung’s bravura performance and Stanley Kwan’s masterful filmmaking, Center Stage achieves just that.

65. The Iron Giant

In a decade dominated by Disney’s renaissance period, Warner Bros. didn’t seem to be able to compete in any way. In what seems to be an effort to stop caring, the studio released The Iron Giant on its own terms. Brad Bird’s adaptation of Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man was his own personal coping mechanism to deal with the death of his sister, who was shot to death during the writing process for the film. As a result, Bird’s film is an angry stare at the futilities of violence as an answer, particularly in fear-driven battles like the Space Race or the Cold War. Imaginative for the children, yet largely substantial for the adults, The Iron Giant is a living nuclear family caricature that carries zero resentment towards a loving time tainted by the stupidities of evil humans. Sadly, Warner Bros. shrugged the film into existence, and it performed terribly in theatres. Luckily, like the titular giant itself, the film continues to exist, thanks to its always important messages, sharp humour, and lovingly produced animation.

64. The Shawshank Redemption

If someone had never ever watched a film before, it seems like the cherished The Shawshank Redemption would be the film many people would introduce this newbie to. Arguably one of cinema’s greatest crowd pleasers, Frank Darabont’s adaptation of the Stephen King short story has enough smarts and cheers for cinephiles of all to enjoy at least something. The ‘90s spawned a number of incredibly overrated films (I won’t name any of them here for my own health, but note their absence as an indication), but Shawshank has too much goodness happening to even be remotely considered for this label. The slow burning fight for salvation is impossible to ignore. Is the film the greatest of all time like IMDb voters have declared? That’s for you to decide. To us, it’s a great film that has the ability to win everyone over, even to some degree.

63. An Angel at My Table

After the critical success of Sweetie, Jane Campion had the opportunity to start the new decade by really showing what she was capable of. So, she went forth with the biographical epic An Angel at My Table: the adapted autobiographical trilogy of author Janet Frame. As we experience Frame’s difficult childhood and adolescence living in privation, we can only hope things get better for her. As she begins to write in the film, we are quickly reminded that we are witnessing Campion’s retelling of Frame’s times of tribulation, being written during these very times. When Frame was rendered voiceless, her writing was her escape. An Angel at My Table is a stunning look at mental health, flawed class and health systems, and a talent full of perseverance.

62. Safe

Arguably a horror film in sheep’s clothing, Todd Haynes’ incredibly layered Safe is as much a commentary on society’s response to the AIDS crisis as it is a warning about the mistreatment of our planet (twenty five years later, we’re not exactly having a good time with that discussion). With a career sparking breakthrough from Julianne Moore, three quarters of this peculiar tale are nauseating to endure. The final act is a completely different film aesthetically; where did the fear go? However, dig deeper, and these are the scariest moments of all: complete security in the face of delusion and obsession. The film also succumbs to this. Distancing yourself and realizing this allows you to see this subterfuge coup de grâce. Safe is anything but.

61. Quiz Show

Maybe Robert Redford’s greatest work as a director (if not, certainly one of his best), Quiz Show is a conventional ‘90s drama based on real events done right. As we follow the rise of new contestant Charles Van Doren and the fall of former American icon Herbie Stempel, we are immediately aware of the corruption found within the once beloved game show Twenty-One. Part depiction of a true story and part political allegory, Quiz Show showcases the strength of money and power to veil the truth, even with something as seemingly innocent as a silly television show. Just when you think Quiz Show will opt for the Hollywood finale, the film goes for the curve ball in the courtroom climax that churns the ending into a bittersweet gut punch, delivering a greater overall commentary for the film and screenwriter Paul Attanasio’s stance on the entire situation.

60. Orlando

Sally Potter's magnum opus is a time shattering, gender-bending, conventions shedding work of transformation. Orlando features the titular character — played to perfection by Tilda Swinton in a breakthrough performance — who is given the order to never pass away, thus remaining youthful forever. As Orlando lives through centuries and even changes from male to female, permanence does not mean a lack of progression. Adapted from Virginia Woolf’s fantastically forward-thinking writing, Orlando is cinematically neoteric (especially for the early ‘90s), and narratively advanced. Even though it's a brisk hour and a half in length, Orlando is the experience of entire lifetimes and histories from a single, wide-eyed perspective.

59. Eyes Wide Shut

The final film in Stanley Kubrick’s near-perfect filmography is a delirious stumble into a secret society, shot in the clearest cinematography. Eyes Wide Shut is a dream-like state for most of its duration, until reality becomes too bizarre to believe. Then it feels authentic, and it’s perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the film. The stories surrounding this film only add to its milieux. Was there supposed to be more unnerving content that was taken out? Was this actually Kubrick’s completed vision? The holes here may have been disruptive when the film was released, but they’re parts of a legend now. Besides, it’s been over twenty years, and not many feels make you feel as much as an intruder in danger like Eyes Wide Shut does.

58. Taste of Cherry

Once Abbas Kiarostami was becoming a more prominent filmmaker in the ‘90s, his obsession with post modernism only became stronger (see his Koker trilogy and docudrama Close-Up for more information). Taste of Cherry features a man who is comfortably at the end of his life, and wishes to be buried after his suicide. Shot almost in documentary style, this drama follows Mr. Badii as he tries to find the right person to help. Attempt after attempt, we only get more confirmation that Badii is content with the idea of death, despite the wishes of his new acquaintances to remain alive. Then, Kiarostami wraps up Taste of Cherry in experimental fashion: by refusing the film to conclude. By breaking the illusion of the film, we see Taste of Cherry being made, proving the narrative has concluded and yet life still goes on. Whether you are in favour of an afterlife or a legacy, Taste of Cherry cherishes both.

57. Naked

Never has verbal diarrhea sounded so engaging. Mike Leigh’s verbose screenplay being matched by an overly enthusiastic (and conspiratorial) David Thewlis performance has made Naked one of the go-to films for a brain cleansing. As thought provoking as it is full of drivel, Naked is absolutely hilarious. Don't let that fool you, as the film is also sincerely profound; sequences like single long shots or the more dramatic third act will quickly remind you of this (if not the frightening subplot of misogyny). This obsidian dark odyssey tale is completely about nothing and everything at the same time, mimicking life’s daily mental overloads of fear-inducing news, harsh realities, and the need to be heard in order to be reminded one is alive.

56. Perfect Blue

Superstardom is a difficult gig, but Satoshi Kon discovered an influential way to represent this in his adaptation of Perfect Blue. Intended to be a live action thriller, the film was turned into an anime instead, likely to be able to capture all of Kon’s blistering visions. Going the extra mile with the amount of intensity and disturbance, Perfect Blue is the kind of psychological thriller that places the viewer amidst every plagued thought, cursing us along with protagonist Mima. Surrounded by toxic fanbases, an obsessive stalker, and deranged managers, Mima’s transition from pop star to actress is a representation of the sacrifices of women performers in an art form hindered by established male gazes.

55. Groundhog Day

Seeing a poor sap being stuck in a permanent life cycle of the same unfortunate day for an eternity is funny, and Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day proves this (especially because Phil Connors is such a jerk). However, even a hateful person can realize the error of their ways and change for the better, and Connors’ predicament becomes a curse that we will him to get out of. By using the opportunity to take advantage of others initially, Connors is the rightful punchline. By having a change of heart and wanting to use this chance to help everyone as much as possible, Groundhog Day turns into a tale of remorse that we wish will work in Connors’ favour. Hilarious, romantic, and endearing, Groundhog Day — despite being the same day repeated countless times — is a re-watchable ‘90s gem for all.

54. Howards End

You won’t forget the name of this Merchant Ivory Productions film, considering the Howards End property is brought up countless times. The ownership of the titular house is important, because of the relationships surrounding who is entitled to Howards End at all times; was it gifted out of respect and/or love, or was it taken away by greed? Clearly, orthodoxy is challenged here, with marriages on the rocks and hidden motives taking the wheel at any time. Although it is pleasant to look at, Howards End is driven by both schemes and honestly established connections, creating a chess game between the nefarious and the good-willed.

53. Barton Fink

The Coen brothers didn’t think it was too early to create this symbolic take on the writing process known as Barton Fink. It begins like any other writers’ block survival story, à la 8 1/2, but we are quickly told this isn’t quite the case through the middle of the film on. The film isn’t so much about Barton Fink himself not being able to write, more than it is about him being able to write well. The insane influences around him certainly don’t help either, as writing is sometimes inspired by life (and his life currently is a surreal mess). Taking a deep dive into post modern territory (like that pelican to cap things off), Barton Fink is the detachment between an artist and reality used to hysterically portray the urgency of completing one’s uninspired work in such an inspired way.

52. Through the Olive Trees

The final part of Abbas Kiarostami’s post modern Koker trilogy, Through the Olive Trees is the fictional documenting of the documentary of a feature film. As Where is the Friends Home? was the feature, and And Life Goes On… was the pseudo-documentary of the aftermath of the previous film, Through the Olive Trees is one additional blurring of the line between reality and fiction, staging events as if they were true. The gorgeous illusion crafted leaps off the screen in all of its graininess. What is a documentary? Is it simply the capturing of life? Kiarostami challenges the current state of filmmaking — in all shapes — and the former cinema of attractions, bringing the art of motion pictures full circle.

51. Election

There’s nothing like having to be spoon fed the current state of politics, yet Alexander Payne and company do the job with the high school satire Election. Pitting a rising star in Reese Witherspoon with a bitter Matthew Broderick playing against type (perhaps in his best role ever), Election likens problematic faculties and supercilious teens to the world leaders that actually run the show. The film isn’t far off, either. What helps is Election refuses to hold back, and makes that abundantly clear very quickly. You figure out this isn’t your typical high school flick. This is Tracy Flick, and she refuses to let dishonesty ruin her academic prowess.

50. Open Your Eyes

What greatly saddens us is how overrun Alejandro Amenábar’s dreamscape drama is by Cameron Crowe’s commendable but subpar remake Vanilla Sky; try finding clips of the film on YouTube, and see how far you get before the latter takes up the results list. Open Your Eyes is much less cluttered, and allows its settings and characters to breathe, which heightens the surreality going on. Even if the twists and turns are obvious to you, not a revelation feels wasted, because Amenábar’s handling of each moment is full of internal wonder, not intended deception. Open Your Eyes is half cautionary tale, and half prophecy of human singularity.

49. Reservoir Dogs

It all started here for Quentin Tarantino. Obsessed with placing all of his favourite cinematic moments in a blender and stirring the contents so they mesh just right, the anomalous filmmaker redefined what an independent film can feel like. Reservoir Dogs is a heist film without ever showing said heist, and it matters not one iota to us. With the ability to take vapid twaddle into the most engaging declarations of the year was clearly a knack Tarantino had from the very first scene, where he goes a little too into detail about his interpretations of “Like a Virgin”. Suddenly, it was clear that we would learn more about this band of criminals by their chit chat than how they mean to represent themselves. With swirling one liners, limited settings and a series of flash backs, Reservoir Dogs made the most of having little to work with, setting a precedent many filmmakers have tried to rip off to this day.

48. Ju Dou

It’s clear by this list that Zhang Yimou dominated this decade, and it all started with his credited joint effort with Yang Fengliang called Ju Dou. The battle between love and legacy is at play at all times, as an abusive husband can’t conceive but his wife and his nephew bond together in their own way. As to not suffer the consequences in 20th century China, their newborn son is represented as her husband’s miracle child. This perception plays into the heads of all involved, including (especially) this son who decides to take after the man he believes is his father. Ju Dou is also shot in exhilarating Technicolor, starting the decade off with the kinds of vibrant hues it would soon be known for.

47. Boyz n the Hood

John Singleton’s debut is easily his finest feature: a nuanced discussion about violence amongst youths in an unsupervised, neglected ghetto. The warning that black-on-black crime remains rampant that begins the film lingers in your mind throughout the story. We’re seeing beautiful minds being held back by danger and a lack of resources, but that’s about it. Singleton uses the majority of Boyz n the Hood to build his characters, including a stunning display of visual world construction (I’m not absolutely certain why Dooky keeps using a pacifier, as I’ve read many possible reasons, but consider me interested). Just like vicious crime itself, Singleton unleashes the film’s more dramatic moments at a lightning speed, because that’s how quickly life can be taken away (either at the end of the gun, or the life of the person pulling the trigger who can never go back). Startlingly mature for such a young and promising filmmaker, Boyz n the Hood is bold, truthful cinema.

46. Rushmore

We know Wes Anderson through and through now. Back in 1998, his quest with ally Owen Wilson was to capture their own version of a Roald Dahl story. With Rushmore, they captured the whimsical Dahl children novels, and a bit of the twisted adult short stories he wrote as well. With a dash of The 400 Blows as well, Rushmore is the naive mind of a teenager that believes he is actually mature. With enough of Anderson’s iconic diorama set design and quirky soundtracks, this is a familiar beginning for what we know now. As for the late ‘90s, this was an extreme oddity, even considerably self indulgent. Twenty years later, we all know better. Not many high school features get the warped mentality of adolescence quite this good. Also, not many sparks in an auteur’s career remain one of their finest works, even with the years of fine tuning this style that have followed.

45. To Live

Even though Zhang Yimou is known for his period pieces, he has proven that he can represent a more contemporary China (1940 to 1970) in just as breathtaking of a fashion as he conjures his more signature works. To Live is the quest to help a family survive, no matter at what cost. Over the years, the Xu family witnesses a changing China without much luck heading in their direction. Yimou is a filmmaker full of hope, though, and he cannot resist the bittersweet epilogue that finds a new life extracted out of the end of misery. To Live is the question of how identity and legacy can be determined out of what life has handed us; it’s somehow a more optimistic work than Yimou was usually releasing in the ‘90s.

44. The Lion King

Arguably Disney’s strongest film during their renaissance, The Lion King was projected by the company as their doomed B-team project next to their next upcoming masterpiece Pocahontas. Was time ever cruel to that latter film. The Lion King — inspired by Hamlet and an “interpolation” of Kimba the White Lion (that’s a discussion for another day — is serious storytelling by the animation juggernaut, with the perfect marriage of lush animation and extravagant music (in score and song form). Since this film was made with the intention to prove early naysayers wrong (and a means of creating the best film possible with the access to Disney’s tools and workspaces), The Lion King is a life story that manages to continue its never ending life of wonder.

43. Central Station

Walter Salles’ greatest cinematic statement to the world was the road trip drama Central Station, featuring a lonely educator-turned-dictation-writer that assumes a maternal position to help a young child find his birth father. With no money between the two of them (and the on-off resentment between both characters for one another), this quest is a trial for both generational figures of rural Rio de Janeiro. The mistranslation of a guardian’s actions to help a child in danger is part of the struggle; does an adult assume the scorn of an angry child to hide them from the evils of reality they are shielded from? Is it the place of an adult that’s not a child’s mother to educate them about real world issues? Central Station is full of sacrifices, all with the aim of achieving the greater good.

42. Boys Don’t Cry

While labeled an awards season darling during the turn of the century, Kimberly Pierce’s brilliant Boys Don’t Cry has surpassed any superficial labels such an honest and uninhibited biopic deserves. Her untainted depiction of Brandon Teena’s life and murder was exactly the kind of progressive statement the final year of the millennium required, especially with the shifting gazes of mainstream film. Before many were willing to openly admit the transphobia and homophobia found in the film industry, Pierce's cinematic exclamation point was impossible to ignore. Unlike the films geared to win awards, Pierce and company were more interested in being heard. Twenty years later, art won over applause, and Boys Don’t Cry is still as powerful and important as ever.

41. Fallen Angels

After the sleeper hit success of Chungking Express, Wong Kar-wai revisited the story intended to be the third part of the film’s story arc; it was dropped as the result of numerous constraints. It was turned into a full length feature (comprised now of its own two halves) named Fallen Angels, and it unfortunately continues to be Kar-wai’s underrated jewel to this day. If Chungking Express was the liveliness of Hong Kong during the day, Fallen Angels was the gloominess of the nighttime underground scene of the same city. Merging Kar-wai’s previous obsession with crime and his then-recent discovery of life’s fleeting ways, Fallen Angels is a shadowy blur, fusing midnight shadows with the guilty secrets of humanity.

40. The Age of Innocence

Martin Scorsese making a tasteful film isn’t exactly a change of pace if you know his body of work inside and out. The Age of Innocence may be his best film of this nature, though. All three players in this period piece love triangle is understandable, which usually isn’t the case (habitually, there’s at least one scapegoat or problematic partner). Newland Archer is convinced to step outside of his comfort zone. Countess Olenska is cast aside from society and is only trying to preserve her identity. May Welland is similarly trying to fit in, by upholding what is expected of her. With tasteful editing, creative camerawork and lighting, and performances that retain more than they ooze, The Age of Innocence is a ballad of torn spirits struggling to stay together. It’s Scorsese at his most reserved, and it’s an intoxicating result.

39. Heavenly Creatures

Peter Jackson is often discussed for his Lord of the Rings achievements, which comes as no surprise. His other works have either been cult classics (Dead Alive), underrated (King Kong), or simply not good (The Lovely Bones). However, one particular film demands to be discussed even on the same level as his Lord of the Rings trilogy: the dismally zany adaptation of real events found in Heavenly Creatures. Turning the real murder by youths Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme (now Anne Perry) into a semi-fantasy retelling via an unstable mind, Heavenly Creatures is darkness cloaked in a new found love of life, hence the unconscionable decision to kill for what feels right.

38. The Watermelon Woman

Cheryl Dunye created The Watermelon Woman because of the necessity of this story being told. Told in a docudrama format, a viewer may be convinced that Dunye made the live action retelling of her findings to reenact how this search for the “Watermelon Woman” (a ‘30s African American actress subjected to stereotyped roles) went down. Then, we eventually discover that virtually none of this is real. There was no “Watermelon Woman”. Most black and queer voices have been scrubbed from archives, or weren't even submitted for preservation. So, Dunye had to make her own story up as a metafictional commentary about the missing histories of marginalized people. Her film is a great success as one of the more powerful cinematic experiments of the ‘90s.

37. Crash

As we all know, David Cronenberg likes to push buttons. To this day, his most shining example of polarity is the disturbing erotic thriller Crash, which follows a group that gets aroused by automobile accidents. Exploring the depravity of complete materialistic ideals, Crash likens the disregard of overly sexualizing the human body to the discarded remains caused by flesh breaking under machinery. The entire film feels like a living store display, as every character is a mannequin, and the shop window clouds up what you see just enough. We are completely removed, staring at this sickness as outsiders. Somehow, perhaps due to Crash's refusal to sympathize with any of the characters, this all works. We're left off with an unfulfilled promise, which only sends us back into the real world colder than ever before.

36. Princess Mononoke

It takes a lot to be Hayao Miyazaki’s ultimate vision, but Princess Mononoke is a lot of a film. Having the world building capabilities that rival Star Wars and the societal vision to take on other great war epics, this fantasy epic is gorgeously animated, and even more beautifully written. Daring in its depictions of humanity’s toxic ecological footprint, Princess Mononoke is an outstanding animated feature that uses its artwork to detail Mother Nature (in mythological proportions) and Miyazaki’s writing to do the scolding. Better yet, the film is far more complex than simply being a battle humanity versus nature: it aims to focus on all of the intricacies that make up society and the impossibility to turn completely around. As magical as it is poignant, Princess Mononoke is anything but safe.

35. Breaking the Waves

It’s hard to see Lars von Trier mock his greatest achievement in recent years, simply because the film is more sympathetic to its characters than his more exploitational works. Breaking the Waves remains profound, because of the focus on Bess’s faith through her crippling naivety, all in the name of coping with her husband’s accident. We wish to shout at the screen to get Bess to listen, but we can’t do anything to stop her from making these horrible, self destructive mistakes, as she listens to the demands of a deteriorating husband and her own interpretations of God. Sure, the final act is largely theoretical, but I think Breaking the Waves deserves some harmony — even if purely fictitious — to counter the suffering of a human soul.

34. Children of Heaven

The power of cinema is the ability to take even just a single object and place eternities within it. In Majid Majidi’s excellent Children of Heaven, that object is a pair of shoes, and what it means to two penurious children, particularly in Iran (where schools are divided by gender). A sister and brother have to share the same shoes, and they swap in between the school’s changeover periods. The extended challenges caused by having to share the same shoes turns into a quest for the older brother, as he vows to get an additional pair no matter what. The bittersweet ending is one for the ages, as Children of Heaven is narratively triumphant but metaphorically damned (in the eyes of a child), and it’s a sensational blending of the real world and a youthful depiction for how the world works.

33. American Beauty

The Academy Awards must have been feeling something at the end of the millennium, gifting Sam Mendes and Alan Ball’s excessively existentialist American Beauty the Best Picture award. Maybe we were all fed up with the sugary lies many of the ‘90s mainstream films were force feeding us. Here was a no-nonsense, hilariously cynical look at the state of America at the end of the nuclear period. Everyone here has their own bizarre notion of how their dreams can be achieved, and most of them are outwardly noticeably unhealthy. American Beauty is the idea that what you are told is happiness isn't, but you may also miss the little things that are beautiful. Sometimes it's a realization of what your role in life is. Sometimes it's a plastic bag floating in the wind.

32. Eternity and a Day

Out of all of the Theo Angelopoulos stream-of-consciousness ventures, Eternity and a Day hits the hardest. Even though there aren't any clear indications that this is happening, it's as if we are coasting into the dreams, memories, or realities of passersby at any given moment, including a wedding ceremony that has nothing to do with us. Although Eternity and a Day secures itself in the real world quite comfortably, being stuck inside the mind of an ailing artist turns the world into a flurry of vignettes that still ease nicely into one another, like the Mediterranean sea converging every droplet of water into a whole. For such an abstract film at times, Eternity and a Day remains peaceful.

31. Days of Being Wild

At the end of 1990, Wong Kar-wai took off to great heights with his second feature Days of Being Wild. Stuck in the ‘80s mindset of aesthetics being the primary focus of a film, this breakthrough feature introduced the perfect pairing of Kar-wai and cinematographer Christopher Doyle to the world, as the film is mostly splashed in different hues of green. Luckily, the story isn’t tossed away, as Kar-wai’s next biggest obsessions — stories of passing ships in the night, the chasing of memories and emotions, and the criminal underworld — are all still very present in this web of plot threads. Chungking Express may have made Kar-wai the international superstar he remains, but the world should have seen this coming with Days of Being Wild.

30. Malcolm X

After Spike Lee was finally starting to be taken seriously after Do the Right Thing, he was the replacement of Norman Jewison to direct a Malcolm X biopic. Lee went as big as possible with this biographical epic, tossing in Malcom X’s own writings, outside perspectives, and Lee’s own cinematic influences all into one riveting feature. At three and a half hours long, without a single second wasted, Malcolm X is nothing but power, excitement, and a much-needed perspective in early ‘90s America. Solidifying Lee and star Denzel Washington as destined greats in their respective fields, Malcolm X is ambition without any excess, with everyone operating at their very best.

29. Secrets & Lies

All of the deception in Mike Leigh’s coruscating drama Secrets & Lies is intended for the greater good. We learn that even little lies have no foundation, especially when it comes to the respect or dignity of a loved one being “protected”. However, Leigh deals with large untruths as well, allowing massive realizations to take place during a family get-together meant to heal the developing divide between siblings and their own loved ones. Secrets & Lies exists through charm and grace for most of its duration, until the inevitable has to happen. Only then can the remedy of togetherness begin to work. Secrets & Lies, while still heavy, is done so tastefully, allowing the drama to feel purely authentic and, in an optimistic sense, resolvable.

28. Fucking Åmål

A coming-of-age, coming-out indie dramedy from Sweden in the late ‘90s is fated to draw some attention, especially considering it’s titled Fucking Åmål. A hate letter to a neglectful town, and a tribute to those that reinvigorate life in us, Lukas Moodysson’s quirky high school time capsule is a whole range of emotions in such a small amount of time. Undeniably a product of its time, the bright colours and popular tracks brighten up this tale of bullying and longing. By the time the film’s change of heart happens — in the dark to hide it from us no less (not that it’s any of our business) — you will know what love is, and how even an unforgiving place like fucking Åmål can take it away from you.

27. La Haine

I’m sad to report that films like La Haine still play an essential part in artistically describing the current state of bigot-driven injustice (that only continues to spread like wildfire). Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine has been one of those ‘90s successes that continue to grow, thanks to the discovery of the film in cinephile discussions or university courses. Even though we see the “now” in the film — through the eyes of three immigrants neglected by society — La Haine represents the many people that are found voiceless in the middle of the ‘90s, when the internet was finally coming around for us all to connect. Twenty five years later, and nothing has changed. We can only try to understand La Haine’s moral conflicts and open-ended discussions and take what we can from this riveting cinematic statement.

26. Boogie Nights

Paul Thomas Anderson’s second feature film Boogie Nights was as large of a leap into uncharted territory as one in his position could have. Right off the bat, he was entrusted with a massive amount of big names, with a two and a half hour long film about the porn industry in the late ‘70s. At least Anderson knew what he was doing, gifting us this rush that crashes down from its high awfully quickly. From exciting to devastating, Boogie Nights is the realization of success that can disappear as quickly as it is granted, particularly in an industry that crushes spirits and exploits its workers like this one (now do I mean porn or do I mean Hollywood?).

25. Farewell my Concubine

Of all the extravagant films Chen Kaige has ever made, none come quite close to the generation defining Farewell my Concubine. The divulgence of two actors that grew up in a Peking opera house feels intrusive, as if we are spying on a decades long relationship that’s not for us to observe. This partnership ranged from professional, to friendly, to even questionably romantic, which is halted due to society’s disallowance of queerness. Playing the role of man and woman for many years on stage, the opera begins to blur with real life. Devastating — especially in part due to the symbolic conclusion — Farewell my Concubine is an epic tragedy that details the tortures of someone not being able to be who they are.

24. Daughters of the Dust

Julie Dash’s opus has seen a lot of attention in recent years, thanks to its anniversary releases, preservation inductions, and cultural influences in the mainstream (including Beyoncé’s Lemonade). Daughters of the Dust is the kind of artistic expression that is clearly inspirational, and yet you have no idea just how hypnotic it is until you sit down and actually watch it. The use of the Gullah language is something you get immediately used to, and it’s refreshingly accurate to hear in a period piece film like this. The lush cinematography turns sandy beaches and humid forests into landscape pieces. The focus on setting over plot renders Daughters of the Dust more of a poem for the ages than a social statement. Like revisiting memories we never personally had, Dash’s visions here are all blessings that will aim straight for the depths of your heart.

23. Unforgiven

After decades of being the figurehead of American westerns, Clint Eastwood finally had enough. He decided to ride off into the sunset in his own way: with a revisionist western. Unforgiven begins relatively normal, as if it is following in the footsteps of a work like Dances with Wolves two years prior. However, those doors are blown off very quickly towards the third act, when we see a protagonist transform into the angel of death. Unforgiven becomes viciously dark (even darker than its already disturbing premise), as a self-sacrifice for the greater good. Eastwood made himself the unmistakable face of evil, whilst changing what westerns in the ‘90s and onward could feel like in the mainstream. Unforgiven as a film and a sacrifice is — without question — the greatest work Eastwood ever made as a filmmaker.

22. The Player

Boasting the greatest all-around cast of all time (appropriately during the same year as the US Olympic “Dream Team”), Robert Altman creates a full Hollywood experience to surround the central story; the biggest names of the time might just be in the background enjoying a cup of coffee. Better yet, we have a mightily engaging neo-noir crime plot to follow (after that still-phenomenal opening long shot, of course). In case you weren’t already fully sold, Altman cleanly pulls off one of the big metafictional twists in film (almost too cleanly). Hollywood is a finicky business, and getting conned by a film about film executives is such an Altman thing to do. If you ever wanted every notion about Hollywood in one experience, here you go.

21. Three Colours: Blue

The first part of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s bravura trilogy is a hyper tragedy that consumes itself in every shade of titular blue under the sun. After two thirds of a family — a father and daughter — are killed in a car accident, the remaining mother cries once, and is unable to ever again. Naturally, the world around her becomes varying hues of blue, as her loneliness envelops her. Blue dives deeply into the psyche of someone experiencing loss, but in intriguing ways: can we mourn someone whose legacy hid our own contributions to their profession, and whose infidelities reveal the remnants of another torn family? Never the filmmaker to deal with topics easily, Kieślowski allows Blue to represent “freedom” in France in a very twisted sense. The lead here is free of familial restraints, but jailed by misery; she must find ways to drift this anguish away in order for her to be truly free once more.

20. Being John Malkovich

In what universe should this film be top twenty material? In an office on a floor between floors, there’s a hole in the wall that’s a portal to the mind of eccentric actor John Malkovich; you get spit onto the New Jersey Turnpike after fifteen minutes. In all seriousness, we only think this is an amazing premise, because we’ve seen what Spike Jonze could do with Charlie Kaufman’s hysterically saddening screenplay. The fact that this film even works as entertainment is enough of an accomplishment. Being John Malkovich being as profound as it is about the human experience, and the philosophies of perception and autonomy? It’s a downright miracle, down to the last “Malkovich”.

19. The Silence of the Lambs

In a decade mostly devoid of stellar horror films (wait until my 1980’s list for more of the genre’s greats), Jonathan Demme started the ‘90s off in a fantastically frightening fashion. The Silence of the Lambs barely featured Hannibal Lecter, yet he stays with us throughout the film. Clarice Starling’s uphill battles are a good portion of the film’s priorities, allowing us to truly connect with the heroine that’s going to be placed in one of the more nerve wracking climaxes of these ten years. As a filmmaker, Demme knows exactly how to tell a damn good story, allowing these talents to heighten the scares that are to come. As a music video artist, Demme savours this artistry for the final act, turning fear into absolute chaos.

18. La Cérémonie

French New Wave was long gone as a trend setting style in cinema by the ‘90s, but some of the wave’s biggest artists used this moment to shine. The greatest example was Claude Chabrol, who used this opportunity to make a graphic retelling of real events: the Papin murders of 1933. Changing the setting and characters, Chabrol’s La Cérémonie is more focused on creating a pair of misfits from the working class that have had enough of the entitled aristocrats they work for. Behind a nuanced performance by Sandrine Bonnaire and Isabelle Huppert having never been more off-the-wall, La Cérémonie is a highly unpredictable affair, even down to how these events are portrayed. The film’s conclusion is Chabrol giving us one last filmmaking experiment, and it’s the final cherry on top of a blisteringly successful story.

17. Trainspotting

Choose life. Danny Boyle’s breakthrough masterpiece Trainspotting is deceptively about drug addiction on the surface; really, it’s about all of us being sucked into capitalist compulsions, and us having to choose the lesser of the evils. With a cast of deviants set to bopping music and a snazzy colour palette, Trainspotting itself is an addictive experience. Sure, we get the ugly side of heroin-driven lives through the story and more ghastly sequences (I know the toilet scene is full of chocolate but it still makes me gag), but the sugary film is exactly what helps us reach these places. Fully understanding the highs and the lows, Trainspotting is a fully fledged exposure of humanity’s need to fill voids no matter in what way (or at what cost), allowing audiences to understand how the protagonists got to this place effectively.

16. Magnolia

Before Paul Thomas Anderson was channeling Stanley Kubrick, he was aiming for Robert Altman. Altman’s Short Cuts (which sadly narrowly missed my list, and we’re still depressed about it) walked so Magnolia could run. Similar in many ways (except instead of an earthquake we get, well, that unforgettable twist), Magnolia is the perfecting of an earlier formula. Toss in some glorious melodrama, metafictional connectivity, and the themes of coincidence and fate, and you get Anderson’s 90s zenith: a masterclass in hyperlink storytelling. What makes Magnolia even greater than it was once perceived is the lingering realization of what is chance and what is coincidence; the unsettling reminder that even all that Magnolia could squeeze into its three hour runtime is far from how serendipitous life truly is.

15. Fargo

Is Fargo the best Coen brothers film of the ‘90s? Oh, you betcha! Featuring the duo’s knack for darkly comedic awkwardness, and the even-more grizzly violence that comes with it, Fargo is a display of the extents of barbaric behaviour. Featuring a kind hearted (but not naive) Marge Gunderson to lead the way, the film seems plotless when it’s really scanning all of the varying degrees of deception and evil for us to foresee before we continue. Being dropped off in the middle of a snow-caked Bainerd is part of the fun. The antics of the goofiest cast of characters you’ll ever see is another portion. Being shielded by one of the ‘90s great heroines cements Fargo as the crime black comedy of the decade, and one of the greats of all time.

14. Raise the Red Lantern

Zhang Yimou’s opus is a slow burning tale of a battle of affection in Warlord Era China. A group of concubines vow for the attention of Master Chen; one of these women is a learned, independent woman forced into the family after death and financial ruin have robbed her of her freedom. The continual backstabbing and integration of these characters makes Raise the Red Lantern less of a test of getting out of this compound, and more a challenge of internal resilience. Once we reach an end, we see a life forever trapped and yet freer than ever before. The aesthetic brilliance of Raise the Red Lantern matches its narrative damnations so vividly, creating a film that transcends an era despite influencing it.

13. Beau Travail

In such a short amount of time, Claire Denis is able to transform visual life as we know it, channel Billy Budd for a new century, and blur the lines between expressive and queer cinema; to this day, Sergeant Galoup’s true intentions are locked in a vault. Beau Travail is part opera and part arthouse poem, stitched together with repression and regret. The foggy-yet-dazzling memories of a sergeant’s final days as an authoritative figure are spellbinding; it’s amazing how much Denis does with so little, in each and every shot, word, or sound effect. When we reach the grand finale — a dance floor anomaly — we’ll never know if we’re in the past, a hopeful wish, or experiencing death. Beau Travail makes the most out of literal and proverbial wastelands.

12. The Thin Red Line

Right after Terrence Malick stunned the world with his second film Days of Heaven, he seemingly vanished into thin air. Nowhere was this singular filmmaker to be found, especially because of his elusive nature. Twenty years later, he finally returned with a film of his that feels like none other he has ever made before or since: The Thin Red Line. Not a part of the more sublimely made earlier works —even including the content (Badlands) — or the ethereal latter works, The Thin Red Line still contains Malick’s spiritualism, but maybe in the most real sense he’s ever crafted. With arguably some of the greatest composed war sequences of all time, and many implicit and explicit internal battles, Malick’s World War II epic is astonishing.

11. Three Colours: Red

The strongest entry in a perfect trilogy is quite the achievement, and Krzysztof Kieślowski’s swan song remains the ultimate letter to the anti romance: a model torn between an obsessive distant boyfriend and a geriatric spy that has stripped sweet nothings of all meaning. How could a world be so cruel, where the ones we love don’t allow us to be free, and our freedom was always being observed by another? Valentine’s quests to discover why the world acts in such a way clashes with her face plastered on a building wall in the middle of a busy intersection. By the end when the entire trilogy gets wrapped up in a twist of fate, Red will remind you that so much of our own flaws are what we control, and yet we have zero command over what life gifts us otherwise: the fortunate and the detrimental.

10. The Piano

Had Jane Campion and The Piano not been released the same year as Schindler’s List, we could have been looking at a female Best Director and Best Picture winner much sooner (although still not soon enough). Easily one of the best made works of the ‘90s, Campion’s magnum opus is this arranged marriage drama, representing the ignored voices of women with a mother who is mute. With a great attention to detail of 1800’s New Zealand, this period piece comes to life in every single little way. Behind a one-of-a-kind performance by Holly Hunter, every cast and crew member pulls off the miraculous: not allowing this to be an acting vehicle of any sort, especially in a safe period like the ‘90s. The Piano is as literally defined as it is many layers of symbols and metaphors, resulting in a haunting, mesmerizing experience.

9. A Brighter Summer Day

Edward Yang has always been unafraid to scale the size of familiar territories (family lives, school systems) into epic proportions. A Brighter Summer Day is four hours, but all of that time is needed for Yang to prove that some devastations cannot be seen coming from a mile away. As the tension between two school gangs heats up more and more, so does life in general (albeit in a more positive way). Songs enter souls. Love fills hearts. The big world is embraced as such, with the fantastic mise en scéne that only a Yang film can boast. In order to know the gravity of death, one must experience all that life has to offer, and no one does that better than Edward Yang.

8. Schindler’s List

Spielbergian cinema has become a bit of a negative attribute in later years, but no one can apply that term to Steven Spielberg’s greatest triumph: Schindler’s List. Shedding off all of his usual habits for the most part, Spielberg used this opportunity to really tell the best story he could; not for himself, but for those that experienced the Holocaust. Oskar Schindler’s change-of-heart is one of the greatest in film, and Spielberg took his time to make sure it was believable at all costs. The film’s refusal to hide anything from us remains impactful to this day. In order to portray a harrowing real event right, a comfortable director had to step outside of the box, resulting in a definitive film for all time.

7. L.A. Confidential

The superficiality of Hollywood is no secret to anyone who has watched movies for over a month. Combining the glossing-over of that industry with another two (the police system and the tabloid magazine press) results in L.A. Confidential: a furiously sharp neo-noir classic. Combining the ‘90s fascination with excessive action and one liners with a story that actually contains major amounts of smarts, this Californian bloodbath is riveting at every single second. Gossip is used to mask other truths needing to be heard (but what else is new?), creating a labyrinth of hearsay and speculation, obviously hitting different pairs of ears in various ways (how do the calculative respond compared to the short-tempered?). If there was ever a film that was narratively complicated and extreme fun on the surface that came out of the ‘90s, it was this crime thriller.

6. Chungking Express

What sets Wong Kar-wai’s breakthrough film apart from his other ‘90s works (or even most ‘90s works) is how nearly impossible it is to describe. It’s split into two halves, both surrounding police officers and the women they fall for (or vice versa). There aren’t any similarities at all, despite setting and the quirks that make us human (eating expiring pineapples as a self-fulfilling effort to get a loved one to return, or breaking into someone’s house just to clean it. That kind of weirdness). Merging surreal aesthetics with the strangeness of humans that operate solely by heart, Chungking Express is the perfect daydream film that feels like your mind refusing to come back down to Earth. Whether one hopes for love or for a better life, Kar-wai has captured our inner monologues that we share only with ourselves perfectly.

5. Goodfellas