Film History: Motion Picture Production Code

Will H. Hays.

Once upon a time, film was becoming a form of story telling. As the initial fascination with the medium as a spectacle wore off, motion pictures were innovated in many other ways: how they were shot, how acting was picked up by camera, special effects, and more (of course, sound would come later). When it comes to sharing stories, any voices can be applied. Then, the birth of the movie star had just begun. With it came the gossip of tabloid rags, scandals attached to famous faces, and other mishaps that plagued the start of the motion picture film industry. So, as was customary at the time, censorship was the way to go. This was applied to many other industries, so why not film? As we keep going, you’ll likely start to see the problem with completely mandatory censorship.

The man for the job was Will H. Hays. He became the first chairman of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPAA) when it was founded in 1922. Does the name ring a bell? Their logo is this interesting image at the end of many films you’ve seen (if you have sat through the credits).

As you can gather, films have needed approval to be released on a wide scale for many years. Again, this association began in 1922, so right in the middle of the silent era. Feature length films with narratives have existed for a number of years now at this point. Hays was formerly a chairman of the Republican National Committee, and, outside of being a part of the Teapot Dome Scandal, seemed like the kind of figurehead to have a no-nonsense policy with cleaning up an industry (his conservative stance helped).

What was the real reason for this association, though? Of course, there’s always a specific incident that spawns such a call-to-action. The MPAA was created as a direct response to the trials surrounding Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, who allegedly raped and murdered rising star Virginia Rappe after a party. Arbuckle was acquitted on all charges, and the case remains mostly a mystery to this day. As a means of keeping Arbuckle out of the industry — no matter what the end result was — and tidying up the face of the film industry (which didn’t have many stars to differentiate from at this time), the MPAA was made. Right off the bat, Hays realized one decision: censoring already existing films is a waste of time and money. In order to preserve the financial hit the industry could have easily had after these trials (and other scandals), cutting up and/or banning already made films was to become a last resort. Instead, Hays and fellow board members worked on a set of guidelines for films to abide by. That way, films would be considered decent enough to show and make a profit, and no money would be spent on additional mending (nor would films cause a stir).

The very first iteration of any ruleset was deemed “The Formula”, and it existed shortly after Hays began his work as chairman.

The Formula (in 1922)

The motion picture studios and the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association came to a gentlemen’s agreement on thirteen elements to be avoided on screen, namely films that:

1. dealt with sex in an improper manner;

2. were based on white slavery;

3. made vice attractive;

4. exhibited nakedness;

5. had prolonged passionate love scenes;

6. were predominantly concerned with the underworld;

7. made gambling and drunkenness attractive;

8. might instruct the weak in methods of committing crime;

9. ridiculed public officials;

10. offended religious beliefs;

11. emphasized violence;

12. portrayed vulgar postures and gestures; and

13. used salacious subtitles and advertising.

Credit goes to Censorship in Film.

By this time, free speech was deemed non-essential by The Supreme Court during the case of Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio in 1915, since films could be used for propagandistic reasons, and a means of instilling evil. So, Hays’ little ruleset could be instilled for studios to comply with, whether they liked it or not. Of course, many complaints were made, and a number of filmmakers vowed to stray away from this list, so it had to be worked on. The Formula became The Don’ts and Be Carefuls: a longer list that contained both strictly forbidden content (the “Don’ts), and the subject matter that needed to be handled tastefully (the “Be Carefuls”). This list was first released in 1927.

The Don’ts and Be Carefuls (in 1927)

Resolved, That those things which are included in the following list shall not appear in pictures produced by the members of this Association, irrespective of the manner in which they are treated:

1. Pointed profanity-by either title or lip-this includes the words "God," "Lord," "Jesus," "Christ" (unless they be used reverently in connection with proper religious ceremonies), "hell," " damn," "Gawd," and every other profane and vulgar expression however it may be spelled;

2. Any licentious or suggestive nudity-in fact or in silhouette; and any lecherous or licentious notice thereof by other characters in the picture;

3. The illegal traffic in drugs;

4. Any inference of sex perversion;

5. White slavery;

6. Miscegenation (sex relationships between the white and black races);

7. Sex hygiene and venereal diseases;

8. Scenes of actual childbirth-in fact or in silhouette;

9. Children's sex organs;

10. Ridicule of the clergy;

11. Willful offence to any nation, race or creed;And be it further resolved, That special care be exercised in the manner in which the following subjects are treated, to the end that vulgarity and suggestiveness may be eliminated and that good taste may be emphasized:

1. The use of the flag;

2. International relations (avoiding picturizing in an unfavourable light another country's religion, history, institutions, prominent people, and citizenry);

3. Arson;

4. The use of firearms;

5. Theft, robbery, safe-cracking, and dynamiting of trains, mines, buildings, etc. (having in mind the effect which a too-detailed description of these may have upon the moron);

6. Brutality and possible gruesomeness;

7. Technique of committing murder by whatever method;

8. Methods of smuggling;

9. Third-degree methods;

10. Actual hangings or electrocutions as legal punishment for crime;

11. Sympathy for criminals;

12. Attitude toward public characters and institutions;

13. Sedition;

14. Apparent cruelty to children and animals;

15. Branding of people or animals;

16. The sale of women, or of a woman selling her virtue;

17. Rape or attempted rape;

18. First-night scenes;

19. Man and woman in bed together;

20. Deliberate seduction of girls;

21. The institution of marriage;

22. Surgical operations;

23. The use of drugs;

24. Titles or scenes having to do with law enforcement or law-enforcing officers;

25. Excessive or lustful kissing, particularly when one character or the other is a "heavy."

Credit goes to the Wabash Center.

Pre-Code

Baby Face: one of the finest examples of a pre-Code film.

So, in the above list, already you can see two threads of thought. The first is the over-sanitization of films, clearly with the intention to cover all bases as to not offend anyone. Ironically, this leads to the second thread: discrimination. Refer to rule six of the “don’ts” section, and you see a mandatory rule forbidding interracial relationships on screen (specifically between black and white lovers). This is strange, considering the disallowance of “willful offence to any nation, race or creed” that comes later on. This is only the beginning of the problematic regulations to come. Unfortunately, the over-abundance of censorship (especially on this level) turns into the silencing of others. Hays’ idea of a clean cut film is the erasure of histories and realities.

Of course, two major events in film history occurred to spice things up a bit. Firstly, sound in film started (hence the regulation about curse words and profanities). After 1927, sound pictures picked up steam, so even a few rules wouldn’t be able to really cut down what the MPAA disallowed. Secondly, the end of the previous wave of censorship occurred. The Don’ts and Be Carefuls were set in place, but no one was caring. This lead to the pre-Code wave of films that tiptoed along the edge of what films could get away with. Works like Baby Face, The Blue Angel, and It Happened One Night (amongst many others) discussed sex, real world struggles (including The Great Depression), backsliding, and other mature topics that the MPAA was trying to move away from. Some pre-Code films also included homosexuality, race relations, and other voices that were being silenced previously.

Pre-Code films got away with this for a little while, until intolerance won. Hays was being badgered left right and centre to resign, since these mature films were being made. It was once the Catholic community in the United States was on the verge of boycotting cinema entirely (this movement was led by Cardinal Dougherty from the Philadelphia sector) that Hays and the MPAA felt the need for stricter change. Film censor Joseph Breen — a devout Catholic — was brought on to promise change, and adhere to the concerns of the Christian community wanting to abandon going to the cinemas. He’s also been attached to strong statements of anti-Semitism, so you can only imagine how well this is going to go (although he apologized and claimed he was no longer anti-Semitic. Right.).

The MPAA seal of approval used to mark a clean film, ready to be viewed.

Now, Breen was in charge of the Production Code Administration (PCA): a sect of the MPAA. This meant that films had to be approved by the PCA in order to be released on a wide scale. At this point, there was no avoiding the code. Speaking of which, we’ve covered The Formula and The Don’ts and Be Carefuls, but where is that infamous Motion Picture Production Code? The one infamously titled the “Hays Code”, much to his chagrin? Well, this is around the time that this finally took place. With Breen on board, previous rulesets and time to fix them, the Motion Picture Production Code (or known as the Hays Code) finally came to be.

This is the first iteration of said Code, which was mandatory for films to abide by. Get ready. It’s going to be a long read.

The Motion Picture Production Code (in 1934)

General Principles1. No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.

2. Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented.

3. Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.Particular Applications

1. Crimes Against the Law: These shall never be presented in such a way as to throw sympathy with the crime as against law and justice or to inspire others with a desire for imitation.

•Murder

•The technique of murder must be presented in a way that will not inspire imitation.

•Brutal killings are not to be presented in detail.

•Revenge in modern times shall not be justified.

•Methods of Crime should not be explicitly presented.

•Theft, robbery, safe-cracking, and dynamiting of trains, mines, buildings, etc., should not be detailed in method.

•Arson must subject to the same safeguards.

•The use of firearms should be restricted to the essentials.

•Methods of smuggling should not be presented.

•Illegal drug traffic must never be presented.

•The use of liquor in American life, when not required by the plot or for proper characterization, will not be shown.

2. Sex: The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing.

•Adultery, sometimes necessary plot material, must not be explicitly treated, or justified, or presented attractively.

•Scenes of Passion

•They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

•Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown.

•In general passion should so be treated that these scenes do not stimulate the lower and baser element.

•Seduction or Rape

•They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

•They are never the proper subject for comedy.

•Sex perversion or any inference to it is forbidden.

•White slavery shall not be treated.

•Miscegenation (sex relationships between the white and black races) is forbidden.

•Sex hygiene and venereal diseases are not subjects for motion pictures.

•Scenes of actual child birth, in fact or in silhouette, are never to be presented.

•Children’s sex organs are never to be exposed.

3. Vulgarity: The treatment of low, disgusting, unpleasant, though not necessarily evil, subjects should always be subject to the dictates of good taste and a regard for the sensibilities of the audience.

4. Obscenity: Obscenity in word, gesture, reference, song, joke, or by suggestion (even when likely to be understood only by part of the audience) is forbidden.

5. Profanity: Pointed profanity (this includes the words, God, Lord, Jesus, Christ – unless used reverently – Hell, S.O.B., damn, Gawd), or every other profane or vulgar expression however used, is forbidden.

6. Costume

•Complete nudity is never permitted. This includes nudity in fact or in silhouette, or any lecherous or licentious notice thereof by other characters in the picture.

•Undressing scenes should be avoided, and never used save where essential to the plot.

•Indecent or undue exposure is forbidden.

•Dancing or costumes intended to permit undue exposure or indecent movements in the dance are forbidden.

7. Dances

•Dances suggesting or representing sexual actions or indecent passions are forbidden.

•Dances which emphasize indecent movements are to be regarded as obscene.

8. Religion

•No film or episode may throw ridicule on any religious faith.

•Ministers of religion in their character as ministers of religion should not be used as comic characters or as villains.

•Ceremonies of any definite religion should be carefully and respectfully handled.

9. Locations: The treatment of bedrooms must be governed by good taste and delicacy.

10. National Feelings

•The use of the Flag shall be consistently respectful.

•The history, institutions, prominent people and citizenry of other nations shall be represented fairly.

11. Titles: Salacious, indecent, or obscene titles shall not be used.

12. Repellent Subjects

The following subjects must be treated within the careful limits of good taste:

•Actual hangings or electrocutions as legal punishments for crime.

•Third degree methods.

•Brutality and possible gruesomeness.

•Branding of people or animals.

•Apparent cruelty to children or animals.

•The sale of women, or a woman selling her virtue.

•Surgical operations

Credit goes to Arizona State University.

So, you have your rules like the hero has to win and the antagonist has to lose, fighting has to be justified, and lovers reconcile (if you’ve ever seen an older film like Gentleman’s Agreement, where a severed relationship is fixed in two seconds before the credits, now you know why). Over the years, the Code kept getting more and more regulations added on. These include some incredibly problematic ones, like “Restraint and care shall be exercised in presentations dealing with sex aberrations.” (a rule to remove homosexuality, queerness, transgenderism and other LGBTQ2+ identities, added in 1961), rules pertaining to abortion (pushing a solely pro-life stance), and numerous others. On the other hand, rules amended to try and be more progressive took place, including the removal of interracial romances; subsequently, rules to remove racist words was implemented. However, at this point, doesn’t this only point out the problem with enforcing censorship like this? One’s own moral compass and biases cloud judgement. How can the opinions of a couple of people speak for everyone, particularly when it involves lifestyles? Rules pertaining to alcohol were made right after the Prohibition era, indicating that laws were also, perhaps, not the best indicators for what’s acceptable to show in a film.

To give you an idea of how much the MPAA scrambled even then to remain a trustworthy board, the Motion Picture Production Code had thirteen (!!!) versions between 1934 and 1966. To see all of the amendments over time, here is a website devoted entirely to the Motion Picture Production Code, created by David P. Hayes (I believe there isn’t any relation to “Hays”, and that his interest on the Code is purely coincidental, but I could be wrong).

Post-Code

Bonnie and Clyde: one of the most important post-Code films.

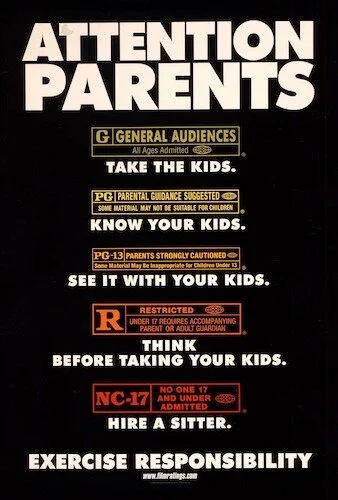

In 1966, Jack Valenti — Special Assistant to Lyndon B. Johnson — was now the president of the MPAA, and he felt the exact same way we all do now and many people likely felt since day one: the Motion Picture Production Code is full of overbearing censorship, and is detrimental to the art of filmmaking. With the rise of underground filmmaking circuits and international markets, it was becoming difficult to control every single film being released. Valenti finally decided it was time to dismantle the never-ending transformations of the Hays Code once and for all. Instead, the MPAA film rating system was created. You know the one:

This way, people of certain ages were allowed to be let into specific films, and motion pictures no longer had to be confined to a set of sterile, misguided rules. Sure, the Motion Picture Production Code began with good intentions (including the safety of children and animals), but it became a flexing of authority and a fist of bigotry that stifled many artists and voices. Before fully implementing the MPAA film rating system, films were flirting with taboo subject matters and anti-rule sentiments for a number of years, and some films were being released under different protocols or via loopholes to get by; how many times can you amend a broken set of rules?

With the ratings in place (note: PG-13 was included in 1984 to create an extra option between family films and mature films), filmmakers could go hog wild. And so they did. Post-Code Hollywood ushered in the New Hollywood movement: filmmakers champing at the bit to tell their stories their way. Something like Bonnie and Clyde could have a gun shot and a wound in the exact same image (the first film to do so). Midnight Cowboy could discuss gigolos and promiscuity. Sure, all of this stuff is fine and dandy, but the main importance was the liberation of voices everywhere. I’m talking the blaxploitation movement, sexually explorative works (and, eventually, LGBTQ2+ representation), and many other important voices that could now be heard. While established filmmakers went overboard with excess (leading to many classics), there wasn’t a set of rules to silence everyone else entirely. Much work was needed, but this was a great start. You can find the MPAA film rating system to be extreme, but at least it isn’t the Hays Code: a bastardized sense of morality that stymied the artistry of many, and treated an entire nation like simpletons.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.