A Critic's Critique of Critics: Roger Ebert

Here and there, we’re going to be looking at critics that have inspired us, or the critics that have given the medium a bad name. We’re in no way insinuating we are better than any of these critics.

Today’s critic is Roger Ebert.

In our new segment titled A Critic’s Critique of Critics, we’re analyzing the biggest names in the film journalism circuit. Can we actually start off with a bigger name than Roger Ebert (aside from his former critic partner Gene Siskel, who we will also touch upon one day)? No. So, let’s start off big. Born in June 18th, 1942, Ebert arrived right in the height of the Golden Age of Hollywood. It only makes perfect sense. America’s most applicable critic was able to look back and forward at the exact same time when he was nineteen and already writing for The Daily Illini. It wasn’t long until he wrote for the Chicago-Sun Times in 1967. What helped was his expertise in writing, and his extensive academic background here, including the University of Illinois, the University of Cape Town, and eventually undergoing a PhD at the University of Chicago (which he dropped midway to become a film critic full time).

His love of film came into the picture while he was perfecting his writing. The parody breakdowns of MAD Magazine alerted him to the fact that films that are glossy on top may not be properly assembled machines underneath. His gift of writing was his means to approach cinema in a similar way (although without the humour, unless he wished to tear a film apart). The rest is history. As a film critic, his insights and reviews during 1974 resulted in him winning the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1975 (the first film critic to do so). With his At the Movies series with Gene Siskel starting in 1986, his views on films were ready to be received by the mass public in a whole new light (Ebert and Siskel originally ran Sneak Previews on PBS starting in 1975; its two iterations carried on until At the Movies began). With a thumbs based rating system that just made sense, Ebert — along with Siskel — became the go-to guy for Americans (and people worldwide) when it came to a quick observation of the latest films of the week.

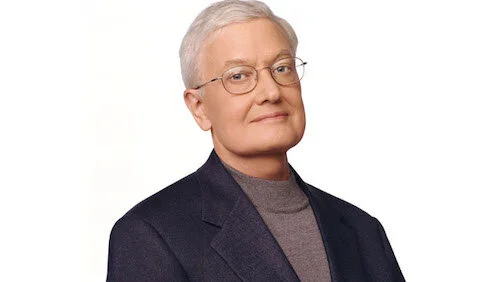

Roger Ebert.

So, how was Ebert as a critic? His cinematic knowledge is the first discussion I’d raise. Ebert himself has a tiny bit of experience in the film industry, including being a screenwriter. His most well known credit is for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls: an incredibly problematic, transphobic parody sequel to The Valley of the Dolls. There’s also the unfinished Who Killed Bambi?: an erotic film starring The Sex Pistols, which Ebert helped write. So, despite being a critic of all films, Ebert found himself writing pulpier works that perhaps didn’t show the best of his ability. Toss in other male gaze sex-heavy works (Up, Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens), Ebert’s screenwriting portfolio doesn’t really hoist his writing achievements up any higher. This kind of viewpoint would also transition into some of his reviews, but only marginally: either not seeing why a film of a particular nature would be damaging, or even the highlighting of a star being gorgeous or appealing look wise.

That’s mainly it for the problems of Ebert, and they may be noteworthy, but I’d consider them hardly defining qualities. Otherwise, any disagreements are entirely subjective. What made Ebert as widespread as he was, was his ability to relate to all viewers and/or readers. If you ever disagreed with him, you’d at least understand where he is coming from. You didn’t have to end up agreeing, either. Did anyone else try and defend Speed 2? No, but his unexpected admiration for the film wasn’t embarrassing to read because he held his own and made his findings make sense to those who could find nothing to like about the film. Despite his expertise in writing, he was never deceptive. He used his craft to convey his thoughts. He willed to get readers to understand cinema more. Even if you weren’t on the same page, you both could love films at the same time, and that’s what Ebert tried to offer the most: a deeper investment of an art form you both adored.

Even though he was popular, that also didn’t get in the way of what he was willing to explore. His Great Movies list was full of obvious picks (The Godfather, Casablanca, that kind of thing) and the fare that common cinephiles may not have dared to go after. It’s a refusal to conform that strengthens the art of entertainment criticism, since it takes readers seriously. Instead of making sure you’re catering to readers, why not let them decide if they wish to jump into the deep end themselves? That’s the kind of ideology I’ve tried to adopt. At the end of the day, you want to champion cinema first and foremost.

Roger Ebert.

He was also able to admit that time is a factor when it comes to criticism. One’s previous mindset won’t be identical to their present observations, and that can get in the way of the dried ink on a review. Being able to look back and admit the harshness of a review of a good film, and the praise of a film that may not have aged too well, is important. If anything, it almost seemed like Ebert enjoyed this unreliability of the critical medium. His Great Movies list was sometimes an apology, since he could then place films he misrepresented on here as a way of saying he gets them now. As a critic, Ebert went almost solely by feel. How did he appreciate the film as a sensation? Maybe at the time, a film just didn’t do it for him, but he was able to understand it better as a connective experience. While risky (since it’s less solid than reviewing a film based solely on fundamentals like editing, acting, writing and more), this type of basis allowed Ebert to remain fluid as a pundit. He never remained set in his ways. He could grow. Maybe if he went back to screenwriting later on in life, he would have churned out something different. We’ll never know.

Relying on how he felt about a film as a viewer was the final thing that made movie goers of all types relate to him. You don’t have to strip a film apart and study each element alone to enjoy going to the cinema. It makes being a critic easier and more reliable, but it isn’t essential for someone to love movies. It’s the rush that many people go for. The tears. The laughs. Ebert rated works on that je ne sais quoi that films can create. It felt like he put these indescribable emotions into words, and defied the impossible. Of course, for cinephiles that study it, he was explaining this type of knowledge in an easy-to-digest way (which is also fine for us). For the rest, he was creating miracles. He related to the masses, but also spoke to the hardcore movie junkies as well by not veering away from what we like either.

Ebert’s final years were rough. He struggled with battles with cancer for over ten years, with wife Chaz Hammelsmith Ebert by his side. He had his jaw removed, but he remained non-threatened and never hid afterwards. He was also open about his ongoing battles. He continued to watch films even while on the verge of dying. His final film was To the Wonder (which he liked by the way: 3.5 out of 4). After he passed away April 4th, 2013, we could only wonder what he would have thought of Roma, Parasite, Moonlight, and countless masterpieces released after his passing. What would he have said about a polarizing work like Joker? Would he have defended some of the works that were maligned? We will never know, even though Chaz Ebert continues to represent his life in full force through various avenues, and RogerEbert.com continues to be run by critics with similar palettes. For critics in general, Roger Ebert helped make the medium as cherished as it can be. For film lovers, Ebert may have helped introduce them to some of their favourite works. For film as a whole, Ebert was a figure that everyone knew, and a different side of the industry that may have been avoided by many until that point. He was one of a kind.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.