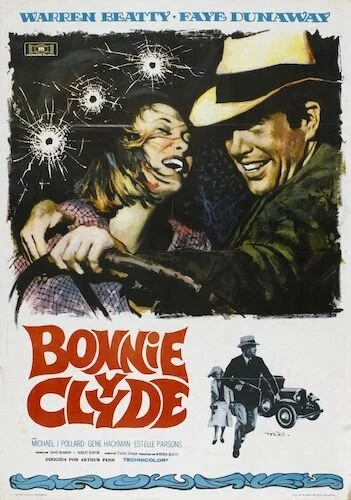

Bonnie and Clyde: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For August 13th, we are going to have a look at Bonnie and Clyde.

The year is 1967, and The Sound of Music just won Best Picture the year before. The ‘60s were still full of glee. Colour was starting to overtake black and white. It was the era of peace and love. Pop music was a massive sensation, and contemporary music was revolutionized. When everything else seemed to be getting brighter in pop culture, the Hollywood Code’s reign had gone on for far too long. So much joy found in films for decades was sterile, and forced into the picture to abide by a set of rules. So, New Hollywood was inevitable. As soon as was humanly possible, American cinema was going to unleash repressed stories and ideas onto the world; in the early ‘60s, films were already cracking through the Code (which led to the eventual end of the Code when it was deemed a futile effort).

It’s only appropriate that one of the figurehead works that generated the New Hollywood movement’s relentless ideologies was Arthur Penn’s finest hour Bonnie and Clyde. It’s fitting that American film history had to change, so this unconventional biopic took literal American history, and went ballistic. The Barrow Gang’s rise and fall — and the leadership of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker — is like a recent brush with the outlaws of the wild west; at least that’s why I think there is such an obsession with this story. There’s a romantic partnership between Bonnie and Clyde, so that fits into society’s fascinations with true love and doomed fates. Either way, this was the story to bring into a turning point in American cinema, and was it ever effective.

Bonnie Parker hearing a noise early on.

Tame by today’s standards (well, kind of), Bonnie and Clyde was a considerable blood bath upon release. It was the first feature film to contain both a gunshot and a created wound in the same shot (something that is heavily taken for granted today). The grand finale is still a macabre hyperbole: an unnecessary overkill of overly killing to the point of distraught hilarity. There’s the rampant sexuality in the film as well; there might not be much in terms of love making, but Bonnie and Clyde is stuffed with innuendos when it isn’t fully previewing more of what’s in store. Then, there are the extra little things that Bonnie and Clyde sneaks in, just when it stomped all over the former Hollywood Code enough, including the underlying theme of Clyde Barrow’s impotence, possibly attached to his hidden sexual fluidity that historians have theorized for years. Toss in some swear words, and it’s all right there: an American film that cared not one iota of how far apart from its contemporaries it may be (despite the fact that 1967 was a benchmark year with other notable New Hollywood classics like In The Heat of the Night and The Graduate).

The thing that makes this film feel special in this narrative is how it was basically a glorified B-picture. Warren Beatty helped bring this picture up from off the ground in a multitude of ways, including script doctoring; he was ultimately the leading producer of this film. When money was tight and getting the right Clyde just wasn’t working out (how can you get the right person with zero budget available), Beatty — who at that point preferred filmmaking over acting — shrugged and decided to fill this role as well; anything to get the film rolling again. Almost all of the other popular names attached to this film, believe it or not, weren’t really big at this time. Faye Dunaway literally starred in her debut picture (The Happening). Gene Hackman was a rising star who Beatty had worked with before in Lilith. Gene Wilder was barely even in this film (though The Producers was going to make him a star this same year). This was only Estelle Parson’s second film role, and she would end up winning an Academy Award as the difficult Blanche Barrow.

Clyde Barrow chasing after Bonnie.

As one can see, the cast was really kind of led by Beatty, who was the only person who was relatively known upon release. Director Arthur Penn may have had a bigger reputation, especially after the popularity of The Chase and the success of The Miracle Worker. It’s these two names that got Bonnie and Clyde any sort of initial attention at all, frankly. It’s what saved the film from actually being a B-picture. Still, it was being treated as such, and was expected to collapse and perish very quickly in theatres. Well, the joke’s on the boring naysayers: Bonnie and Clyde was so successful (making seventy million against a budget that was just under three million), it became a precedent for box office returns. Its numerous Academy Award nominations solidified it as the current standard, if anything. Counterculture cinema was somehow becoming the culture.

If all of this success was off the basis of thrill seeking and cinematic insurrection by a displeased American crowd, then Bonnie and Clyde would just sit as a point in time. However, the fact of the matter is it’s simply a spectacular film through and through, and all of its provocations are asides (well, outside of the violence attached to the story, representing the true danger of these situations). The film starts off sexy, in a way that’s knowingly slimy, distancing us from Bonnie and Clyde right away; it’s almost funny how much sexual frustration is between the two characters instantly, and just putting in phallic imagery and blushing only makes it a riot. Things are playful, and the cast seems invincible, only until the first sign of blood appears. Suddenly, this whole bank robbing thing is kind of a big deal. There’s no turning back now. We’re following murderers. They know they’re murderers. They assume this label, and go all in.

Bonnie and Clyde indulging in those phallic symbols (through corporate imagery to boot).

So, you know from the very beginning that Bonnie and Clyde is going to press its luck, but it tests the waters with each and every turning point. Somehow, not much here feels exploitation, because of how calculated the excess is. Everything here is used to tell a story, but there’s at least a superb story being told at the very base of this picture; a criminal family has gone too far, and a newer participant (Bonnie) is realizing how separated from her former life she now is (amongst other subplots, all dealing with association with criminal identities). Any wavering or commitment is riveting to behold; it’s as if we’re seeing the American populace respond in different ways to a new era of violent, indulgent cinema. The actual shootouts — for what they’re worth — are still sensational, and style supersedes the desperation to feature shooting guns (like the wait for decades of safe cinema for this was well thought out and worth it). What helps maintain these moments still is the fact that they are aesthetically pleasing, with crazy shots of breaking glass or destroyed furniture, impactful editing that zips to establishing and reaction images, and the bursts of insanity after prolonged dread.

As self aware as Bonnie and Clyde is, that means it’s also observant of what it should be doing right at all times. A family picnic is filmed like personal home footage. The Barrow stomping grounds are more dismal than the towns they destroy. Even the climax (the climax of all climaxes) is almost poetic amongst its over-the-top carnage, with the devastating lead up of extreme close ups (almost like a silent film), and proper slow motion passages to help you catch your breath. As extreme as Bonnie and Clyde aims to be, it never forgets the cinematic language, and takes full advantage of what can be done now. These are new portals for good. There are countless ways to expand what the best filmmakers were doing before now. This is a time to prove that these kinds of stories told these ways are worth it.

Weary eyes resting upon a scene of bloodshed.

Between Bonnie and Clyde and the other game changing New Hollywood early works, American cinema really was never the same again. Like Bonnie knowing she couldn’t return home now, it was impossible for Hollywood on a mainstream level to return to goody-two-shoes pictures that ignored the evils of the world. This violence, sexuality, commentary, and vision was now engrained in the major motion picture. It was championed with Oscars, for crying out loud. It’s no surprise that an offspring — Jaws — became the first blockbuster ever. Of course both Godfathers would come around the corner.

In 2020, Bonnie and Clyde is attached to this movement that remains influential and appreciated over fifty years later. Upon release, this was almost like discovering a new drug and knowing you could now feel this way within the timeline of your life from here on out (no wonder why many were opposed, I suppose). It’s impossible to feel threatened by Bonnie and Clyde now: a testament to how much cinema in America has since changed. It is, however, possible to feel enthralled by Bonnie and Clyde now: a testament to how fundamentally striking the film is. The infamous tale of the Barrow Gang continues to live, now as a groundbreaking film that created new rules to replace the very ones they chose to ignore.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.