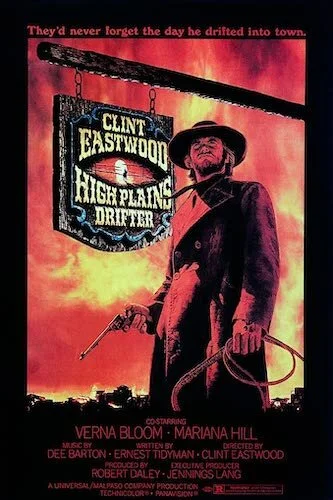

High Plains Drifter: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For August 22nd, we are going to have a look at High Plains Drifter.

It didn’t take Clint Eastwood very long to try and change the rules. His second directorial effort High Plains Drifter was so anti-western, it bothered even John Wayne, who despised the film and claimed that this is not what the genre was all about. Unlike some of Wayne’s other dislikes (*ahem* High Noon), it’s much easier to see what set him off with Eastwood’s revisionist tale of the most evil protagonist in all of the western genre. Only a few scenes in, and you know you’re going to hate Eastwood’s nameless outlaw who is unlike the “man with no name” (from Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy) in so many ways. You wanted to get to know the man with no name. You hate everything about “The Stranger”. You reel into your chair and stare, knowing you’re going to be watching a disgusting being try to save the day. You do it for the town of Lago. You must. You have to have hope for them.

Ernest Tidyman’s screenwriting was always daring to get audiences to view more uncomfortable scenarios or protagonists; his work includes inventing John Shaft (obviously of Shaft fame) and The French Connection (which boasts corrupted detective Popeye Doyle). He goes borderline too far in High Plains Drifter, having “The Stranger” rape a female citizen of the town extremely early into the film. By 2020’s standards, this is quite a terrible look that only ages more and more poorly. I understand that its motive succeeds: we hate “The Stranger” immediately and only hate him more the longer the film goes on without any remorse (we eventually can put two and two together, knowing he won’t ever apologize). I suppose getting us shaken to our core works. It’s a tactic that is completely inexcusable now, and I’d argue it was hardly excusable even in 1973. However, once again, it works. We hate Eastwood’s lead character minutes into High Plains Drifter. Success, I guess?

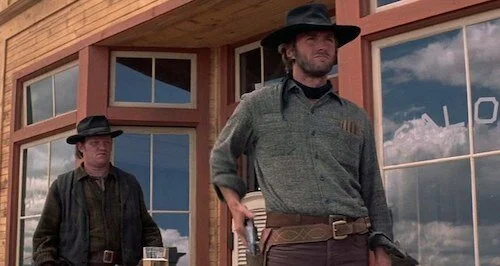

This town wasn’t like this earlier, I swear.

Once you can get past, well, that little detail, you’re going to understand how against type High Plains Drifter is. You don’t side with the villains. You certainly aren’t rooting directly for the protagonist (an antihero that makes Travis Bickle seem sane in comparison). You’re one of the townspeople, and it’s a fascinating position to be in. You’re helpless. You know the town is in danger, and this stranger is supposed to help. Instead, The Stranger takes advantage of all of his perks: selecting who he wants to be sheriff, having his living quarters redesigned, and more. When he finally gets his schemes into motion, you’re wondering what he’s even doing. Why is the town being painted red? Does this benefit anyone outside of himself? It’s these painful questions that slowly reveal the impact of the film’s true intentions: we’ve been following the devil for the entire time.

I’m not going to go with the “ghost” idea that others have theorized, because The Stranger is full of selfish desires, geared by his sinister design. He turns the town into hell (no, seriously) so he feels more comfortable, as if he is right at home (I know it’s to put fear into the villains’ hearts, but come on). As unsettling as this all is, this is one of the rare westerns where the film can go virtually any way, and being suspended in mid air for an entire feature film truly is extraordinary. If the goal of a revisionist western is to destroy any preconceived notions one had of the genre, High Plains Drifter most certainly fulfils that criteria. You’re left wondering what in God’s name you’ve just watched by the end of it: crimson and all.

Make way for one of the least likeable antiheroes in film history.

So, yeah. I can see why John Wayne hates this. There’s no muscular hero riding into the town on horseback with the sun behind him, saving the day as cowboys did for decades and decades and decades. This was the antithesis of the common protagonist that decimated any hopes we had for a town in need. There is no redemption. There is no change of heart. You are stuck with a demon that can do anything at any time. That’s borderline frightening. Out of all of Clint Eastwood’s early efforts, High Plains Drifter works the best, because it is so challenging from right off the bat. Sure, maybe some of its approaches really haven’t aged well (rape is a topic I find needs to be approached extremely well, amongst others, otherwise it is an offensive, insensitive trope)/ On the other hand, it’s a rare western where you virtually have no idea how it will progress, never mind how it will all end. What might put off some viewers is how willingly High Plains Drifter leaves audiences out in the dark to fend for themselves. The film doesn’t care about you. It’s kind of refreshing, actually (even fifty years later).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.