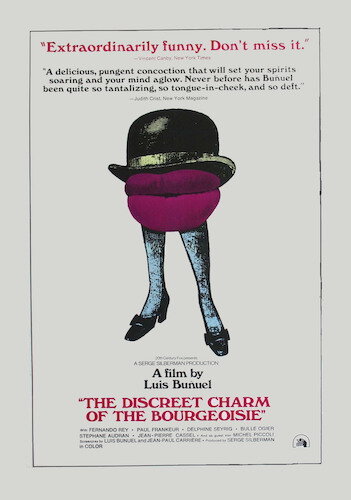

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For September 15th, we are going to have a look at The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

By the early ‘70s, Luis Buñuel was beyond past the point that many filmmakers would be burned out by. An auteur since even the silent era, Buñuel had helped revolutionize shorts, arthouse, satires, surreal pictures and more. Five different decades reached The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and Buñuel had churned out many fantastic pictures before then. However, Discreet felt almost like a “best-of” collection for the Spanish artist, considering all of its individual parts being smushed in. The pseudo realism that turns into a nightmare is like Viridiana. The aristocratic dinner gone wrong is similar to The Exterminating Angel. Even some very specific images come out of his other works, including a scene that had to have cockroaches (almost identical to Un Chien Andalou). The strongest aspect of this point is how Discreet is still very much its own film, and is arguably Buñuel’s finest hour to boot. Somehow, it feels less like a series of rehashed ideas, and more like the total of various parts combined together to create the ultimate vision.

So, naturally, Discreet pokes fun at the upper class, as was really common for Buñuel (when he’s not mocking religion or politics or other systems). The goal is simple: the party of half a dozen (or so) want to have dinner. Invitations have been sent out by a wealthy couple to other important figures, including ambassadors and the like. We start off with a bit of a miscommunication: the wrong details were given out, and the dinner is actually happening at another time. Seems reasonable enough, right? So, we see the news get received well enough (though not perfectly), and await this fine feast another time. Then, something else slips up the occasion. Then another. Then another. Soon enough, our patience gets tested, because of these mundane excuses to not fulfill this hyped up supper of the century.

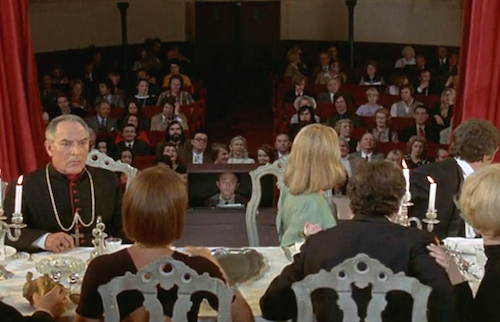

The dinner party searching endlessly for food.

Buñuel likes to toy with his audiences, but he doesn’t necessarily want to torture us. So, eventually, this laundry list of unfortunate events start to get weirder and weirder, distancing us from the film. It’s no longer about us wondering when this pack of six elites will eat; instead, we await what additional absurdity is on the menu next. Connecting with the fallen soldiers of war, the dearly departed, and other woes that the wealthy need not be concerned with, we get some startling commentary by Buñuel amongst all of this fun. He’s making satire, but he wants you to know why. He has a big problem with the communities that neglect everyone else. So, he dangles luxuries in front of the faces of the one percent, and watches them flail. When the poorer classes woes get injected into the mix, Discreet really shows its true colours, and how minuscule this dinner really is in the grand scheme of things.

But, Buñuel isn’t finished yet, and has to get weirder. At some point, it is revealed that we are in the dream of one of the party members (which is actually the dream of a different member, and then another, and then…), and that’s when Discreet really takes off with its premise. I recall the very first time I watched this film many years ago, and being told it was a surreal masterpiece and I wasn’t quite sure where the “surreal” nature of it came into play. Well, eventually I was given my answer. Once Discreet gets going, it becomes only surreal, with so many implausibilities and frightening images and confusing premises colliding together at full speed. At this point, Discreet is now hysterical. We don’t care about this dinner. We’re just trying to make sense of it all, whilst trying not to laugh at the dismally dark humour and hide from the more frightening images.

Discreet combines dreams with ghosts in some instances, blurring the line of the mental and spiritual sides of the subconscious.

As strange as Discreet becomes, there is an endless synergy keeping the film together. Maybe it’s anticipation. Maybe it’s confusion. Either way, the next scene is always awaited, even though it’s apparent that sense has been thrown out of the window minutes ago. Being suspended in the air like this is actually enticing. There’s zero expectation from hereon out. Right until the credits (which are their own form of punishment for the guests), Discreet is a parade of unusual sequences that are all connected with their dinner premise, but otherwise have zero relevance to one another. Oddly enough, a story that has borderline zero narrative semblance in the traditional sense was nominated for an Academy Award, particularly for screenwriting (it won for Best Foreign Language Film, though). Something about this film just connects with people, particularly us common folk. We’re not sadists, we swear.

Again, the heart of the film shines with its subplots of allowing the non-elite speak, and become a part of the story. Sometimes, their words overtake the picture; it’s an early sign that reality is fabricated here, but it’s also nice to see a different perspective. Even in its more maniacal moments, Discreet doesn’t get completely off track, and includes some fairly heavier confessions or events. In Buñuel’s typically off-centre fashion, Discreet remains batty enough so that these moments of clarity and severity still fit amongst the silliness that’s bouncing off the walls. It also ties everything together; the political turmoil rumbling underneath the set figuratively leaks into the jokes and the fears. The coup de grâce later on in the film (almost in a literal sense) may seem completely unexpected, but really this is all according to Buñuel’s unique perceptions of civilizational corruption, crushing together in ways we’re not really used to.

In The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, dinner becomes the show.

Because Discreet starts off relatively normal, Buñuel flexes his expertise of the subconscious by easing us into this insane world. Like a real dream, we almost feel like we don’t know how we got to where we are, which is actually fairly normal for a film; the establishment of a setting and its characters is a way of clarifying this new world that we’ve been dropped into. Even though, again, this caught me off guard when I was younger, it’s a slow development I appreciate greatly. The Phantom of Liberty — another Buñuel surreal classic — is clearly strange right away. There’s also the off chance that you went into Discreet blindly and not knowing its true nature, and I would love to ask how crazy you believed you were becoming as the film proceeded. Otherwise, you likely knew the film was going to be at least a bit unusual, given who made it. Even still, Buñuel’s procedure allows the film to naturally get to places you don’t expect, still surprising you.

In a metaphysical form, much like the start of the film, the film itself is a tool for much of the other disturbances. Cuts act as additional barricades blockading these starving guests. Juxtaposition allows the unnatural to become organic. Again, need I remind you of the credits that feel Monty Python-esque, as they wrap up the film before a proper chance for redemption is had? Buñuel clearly made this for our enjoyment, but he has rendered us evil in return. Even if we don’t feel so judgemental of the elite, we share his vision even for a little while. I mean, try and watch Discreet without laughing or feel enjoyment. It’s borderline impossible. Thanks, Luis…

One of the many memorable surreal images in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

Buñuel only had two more films after The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and both were fantastic successes (The Phantom of Liberty and That Obscure Object of Desire). Both tried to break film’s conventions in similar ways that Discreet did (even though Buñuel clearly was experimenting since he started making motion pictures). However, even after the fact, Discreet feels like his strongest achievement (which is astonishing, given the amount of perfect works he had churned out), more or less because it feels like a stew made with all of his strengths at their height. If we want to include his melodramas like Viridiana and Los Olvidados, then Discreet is certainly his greatest satire (which is one style he certainly specialized in). Not many films are this condescending, patronizing, or relentless with its loathing of the wealthy classes. Buñuel cared about filmmaking, but he didn’t care about the subjects he reviled. It’s a hilarious hatred, really.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.